In October 2021, a Tesla with Autopilot enabled was involved in a collision. The vehicle in front of the Tesla stopped suddenly and, as the investigation by the Netherlands Forensic Institute showed, the driver reacted in time to the warning system and took back control of the car. The crash still occurred because the Tesla’s Autopilot miscalculated and followed the vehicle in front too closely, especially considering traffic density.

After the accident, the investigation team decided to hack into the vehicle’s data storage system rather than rely on data from Tesla in order to ensure the objectivity of their findings. Not only were they able to successfully decrypt the pre-crash data. Interestingly, they also discovered that Tesla electric vehicles (EVs) store much more information than was publicly known, such as the vehicle’s speed, positions of the acceleration pedal and steering wheel, and braking behavior. This data would greatly help forensics experts investigating a fatal accident, especially in a criminal inquiry.

In April 2022, researchers at the University of Oxford and Armasuisse S+T identified a new cyberattack that enables hackers to remotely disrupt the EV charging process.[1]https://www.researchgate.net/publication/358402319_Brokenwire_Wireless_Disruption_of_CCS_Electric_Vehicle_Charging

In May 2022, thieves stole two cars in a neighborhood in South Austin, Texas, without having access to the car keys by using nothing more than a portable digital hacking device.

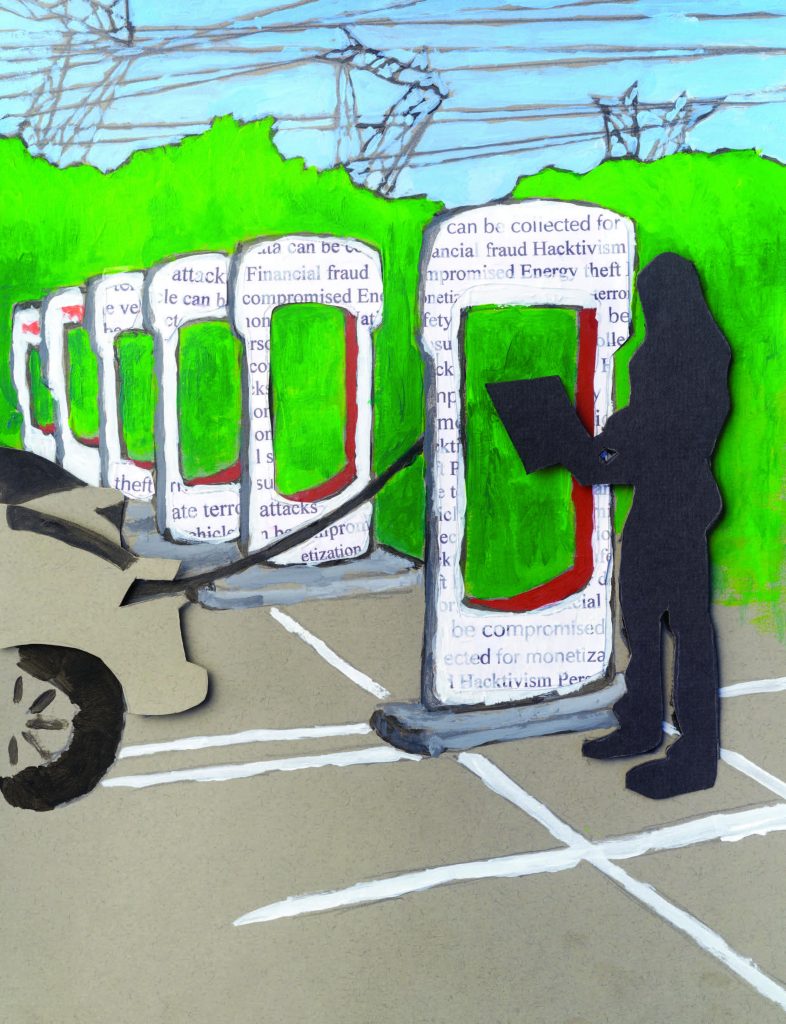

EVs and the EV charging ecosystem have become a playground for hackers—both legal and illegal—since safety and privacy policies are in their infancy. Upstream Security’s 2021 Automotive Cybersecurity Report noted a 225 percent increase in vehicle cyberattacks on cars from 2018 to 2021 and projected that cyberattacks will cost the automobile industry $505 billion by 2024.[2]https://www.israel21c.org/cyberattacks-on-cars-increased-225-in-last-three-years/ As EVs increase in popularity, security and privacy challenges need to be addressed before the EV ecosystem can achieve mainstream adoption.

Half a Million EV Charging Stations

Low maintenance, improving battery performance and the perception of eco-friendliness have made EVs an attractive alternative with more demand than can be fulfilled. [3]https://www.latimes.com/business/story/2022-04-01/high-gas-prices-drive-ev-demand-but-supplies-short This has been further spurred by rising gas prices, which have surged by 116 percent in the U.S. since the beginning of 2021. [4]https://www.eia.gov/dnav/pet/hist/LeafHandler.ashx?n=pet&s=emm_epmr_pte_nus_dpg&f=w Last year, 535,000 EVs were sold in the U.S. and 305,000 in the U.K.[5]https://insideevs.com/news/565442/uk-plugin-car-sales-january2022

Included in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, enacted last fall by Congress as the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, is a $7.5 billion[6]https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2022/jun/8/biden-unveils-rules-for-nationwide-network-of-5000/ allocation to build 500,000 charging stations.[7]https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/03/07/fact-sheet-vice-president-harris-announces-actions-to-accelerate-clean-transit-buses-school-buses-and-trucks/ The Department of Transportation (DOT) published a toolkit on its website to inform the public and disseminate information about the installation and operation of the new EV infrastructure, including best-practice guidelines for the planning and maintenance of charging infrastructure.[8]https://www.transportation.gov/sites/dot.gov/files/2022-01/Charging-Forward_A-Toolkit-for-Planning-and-Funding-Rural-Electric-Mobility-Infrastructure_Feb2022.pdf However, the increasing challenges that cybersecurity threats pose, as well as effective precautionary measures, are missing from the toolkit.

In June 2022, DOT and the Department of Energy proposed new standards to increase the convenience and reliability of EV charging infrastructure.[9]https://www.cnet.com/roadshow/news/biden-administration-proposed-ev-charging-standards/ Yet, developing and implementing plans to deal with most cybersecurity threats is left to individual states.

Nation-State Attacks

The transportation sector is one of 16 critical cyber-infrastructures in the U.S., designated by the Cyber-security & Infrastructure Security Agency as potential targets of nation-state sponsored terror attacks.[10]https://www.cisa.gov/critical-infrastructure-sectors

In recent years, nation-state attacks have increasingly disrupted American businesses and government agencies. According to the Microsoft Digital Defense Report, Russia is responsible for the bulk of nation-state cyberattacks (58 percent), followed by North Korea (23 percent), Iran (11 percent) and then China (8 percent). Between May 2021 and March 2022, for example, a Chinese state-sponsored hacking group, known as “Hafnium,” infiltrated at least six state government departments, culminating in a major exploit of the Microsoft Exchange Server software.[11]https://www.cnbc.com/2021/03/09/microsoft-exchange-hack-explained.html The Exchange Server is a popular software used for providing corporate email services. Exploiting this vulnerability afforded Chinese cyber espionage an entry point into the networks of as many as 30,000 victim organizations, including small businesses, towns, cities, local governments and defense contractors. Predictably, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs denied any involvement.[12]https://www.cnbc.com/2022/03/09/china-state-backed-hackers-compromised-6-us-state-governments-report.html

In March 2022, the Federal Bureau of Investigation issued a threat warning for American energy systems and other critical infrastructure, stating that Russian hackers were scanning our energy sector for vulnerabilities, as well as conducting reconnaissance of our military defenses.[13]http://www.reuters.com/world/fbi-says-russian-hackers-scanning-us-energy-systems-pose-current-threat-2022-03-29/

In recent years, U.S. agencies have been prosecuting hacker groups targeting critical infrastructure. In March 2022, federal prosecutors charged Russian officials involved in hacking campaigns that included the energy sector.[14]https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/mar/24/us-charges-russian-hackers-cyber-attacks In another incident, a 36-year-old research institute employee at the Ministry of Defence of the Russian Federation was accused of conspiring to hack an oil and gas refinery system in the U.S. and install what is known as “Triton” malware. Triton can communicate with the controllers that manage petroleum-refining operations and transmit halt commands.

Most significantly, in January 2022, Russia’s domestic security agency (at the request of the U.S. government) arrested 14 alleged members of REvil, a hacker group[15]https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2022/01/14/russia-hacker-revil/ that American officials say masterminded the Colonial Pipeline attack, which crippled East Coast gas supplies last year.[16]https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/08/us/politics/cyberattack-colonial-pipeline.html Colonial Pipeline supplies gas, diesel and jet fuel, and about 45 percent of all East Coast fuels arrives via this pipeline. In May 2021, hackers gained remote entry to Colonial Pipeline’s servers through an abandoned Virtual Private Network (VPN) account whose password was leaked onto the dark web. VPN accounts give employees remote access to company networks, and the accounts must be deactivated as soon as no longer in use.

The hackers planted DarkSide malware,[17]https://www.trendmicro.com/en_us/research/21/e/what-we-know-about-darkside-ransomware-and-the-us-pipeline-attac.html a relatively new ransomware used for targeting high-revenue organizations. Ransomware is the term given to malware engineered to block access to a computer system, typically by encrypting or scrambling data stored on that system until a ransom is paid. DarkSide’s malware is a particularly nasty strain that executes a double extortion tactic by infecting the network domain controller, spreading to other machines and stealing data before finally encrypting it. About 100 GB of data was exfiltrated from Colonial Pipeline’s servers.

All operations of the 5,500-mile pipeline were halted for a week to prevent further spread of the ransomware, wipe the affected machines and recover from the damage. This caused a gas shortage, which lead to panic buying. The company ended up paying a ransomware bribe of about $5 million to retrieve the stolen data.

Ransomware Tsunami

The cost of ransomware attacks on the automotive industry, including Honda,[18]https://techcrunch.com/2020/06/09/honda-ransomware-snake/ Toyota,[19]https://www.zdnet.com/article/toyota-australia-confirms-attempted-cyber-attack/ Nissan and Renault[20]https://www.thenationalnews.com/business/carmaker-nissan-says-uk-plant-hit-by-ransomware-attack-1.69769 increased massively from $6.9 million in 2019 to $20 billion in 2020[21]https://www.otorio.com/blog/ransomware-the-cyber-attacks-on-the-automotive-industry/ and is expected to top $50 billion by 2023. Russian hackers have even bribed Tesla employees[22]https://www.tripwire.com/state-of-security/featured/closer-look-attempted-ransomware-attack-tesla/ with million-dollar payments to plant malware in the company’s servers enabling malicious access.

Yoav Levy, CEO of Upstream Security, which provides automotive cybersecurity platforms, reports a rise in attacks on both charging stations and EVs.xxiii Dishonest owners can hack into the charging station to avoid paying usage fees. Hackers can lock up charging terminals and prevent EV owners from charging their vehicles until a bribe is paid. Vehicle fleet owners, such as car rental companies, are much more susceptible to such attacks than are charging station homeowners, as preventing the fleet from charging will stall business operations and force the owner to pay a large ransom.

Hacktivism

Hacktivism, a mix of “hacking” and “activism,” is increasing due to charging infrastructure vulnerabilities. Early in the Russian occupation of Ukraine, a Ukrainian hacker injected an abusive message about Putin into a charging terminal display on a Russian motorway.[23]https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/putin-charging-station-hacked-ukraine-russia-b2026260.html A similar incident occurred in the U.K. when hackers displayed pornographic content on charging station display screens.[24]https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-hampshire-61006816

Researchers have demonstrated how easy it is for miscreants to halt an entire fleet of electric ambulances parked at a station from charging using malicious radio signals.[25]https://www.telegraph.co.uk/business/2022/03/29/security-flaws-leaves-electric-cars-risk-cyber-hacks/ Dubbed the Brokenwire technique, the attack involves placing a small off-the-shelf radio transmitter, called a software-defined-radio, within 50 yards of the charging station. Then the charging station is bombarded with constant radio signals causing a denial-of-service condition whereby the station stops charging all cars immediately. The only way to resume the charge is to physically walk up to the charger and unplug it and then resume the charging process.

In April 2022, several charging stations on the Isle of Wight, U.K., were hacked such that inappropriate content from pornographic websites was shown the display screens.[26]www.news18.com/news/buzz/ev-owners-shocked-after-hacked-charging-station-screens-show-pornographic-photos-5070415.html The hackers also made the charging stations unavailable: Every time a customer tried to use the station, it rebooted. However, no ransomware demand was reported.

Personal Safety

Personal safety while driving in an EV can be compromised by hackers exploiting onboard vulnerable apps to unlock doors, open windows or flash the headlights.[27]http://www.vice.com/en/article/akv7z5/how-a-hacker-controlled-dozens-of-teslas-using-a-flaw-in-third-party-app In 2016, a similar attack on the NissanConnect app allowed hackers to control an EV’s air conditioning.[28]https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2016/feb/24/hackers-nissan-leaf-heating-access-driving-history In another instance, hackers exploited a popular car communications app called UConnect, forcing a Jeep to drive into a ditch and caused Chrysler, one of the brands using this app, to recall 1.4 million vehicles.[29]https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-33650491 Such attacks in future might prove fatal.

Numerous vulnerabilities exist in wireless protocols used in the design of keyless technologies that make EVs, as well as other vehicles with keyless technology, susceptible to car theft. The simple “relay attack” was used in multiple car thefts in South Austin, Texas, in May this year. The attack only requires two inexpensive Bluetooth radios, which the hackers configured to redirect Bluetooth communications normally used by keyless-entry fobs. To execute, the thieves place one of the devices next to the car they are targeting, when parked in the owner’s driveway. The other device is placed just outside the front door of the house, presumably near where the owner left the car fob on the other side of the door. Signals emitted by the fob are automatically relayed from one device to the other, creating the impression that the owner is located close to the vehicle, allowing the entry system to be fooled and the thieves to drive off with the car.[30]https://fortune.com/2022/05/17/tesla-hacker-shows-how-to-unlock-start-and-drive-off-with-car/

The hacking device also works with smartphones. Since the device can pick up signals anywhere within 15 yards of the phone, placing the smartphone outside the bedroom window where the owner’s smartphone is charging, for example, will also enable an attack.

Energy Theft

Energy theft will increase with EV use since recharging tightly couples transportation and the power grid. Recent research involving multiple universities analyzed the management software at 16 charging stations by examining the charger firmware, as well as the mobile and web applications customers use to interact with the charger.[31]https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0167404821003357 The authors found several web-server vulnerabilities in the products of several companies. Additionally, they found that by exploiting these vulnerabilities attackers can control the charging processes, modify firmware settings, change the billing, access personally identifiable information and even recruit the system for botnet operations (which use smart devices as a hacking device to attack another device or system). They concluded that hacking operations can also indirectly cause service disruptions and even failure in the local electric grid, which could initiate a cascading effect on the national grid.

EV owners sometimes use their car batteries for crypto mining. One Tesla owner claims to earn $800 in bitcoin every month by rigging his car battery to run mining software.[32]https://thehill.com/changing-america/enrichment/education/589045-how-tesla-owners-can-mine-cryptocurrency-with-their/ However, mining for cryptocurrency might void the car’s warranty. On the flip side, EV automakers such as Ontario-based Avvenire are adding provisions to allow crypto mining while parked. However, this will shorten the life of the EV battery.[33]https://news.yahoo.com/this-electric-vehicle-mines-crypto-in-its-free-time-191748861.html

Cryptojacking private EVs, by hacking the battery to mine cryptocurrency without the owner’s knowledge or permission, might soon become a threat. Already cryptojacking attacks have been mounted on the automotive industry. In 2018, hackers infiltrated Tesla’s cloud servers through an account that was not properly password protected. They planted cryptojacking malware called Stratum in their Amazon Web Service accounts to mine cryptocurrency using the cloud’s computing power.[34]https://www.investopedia.com/news/teslas-cloud-was-hacked-mining-cryptocurrency/

Private Data

The illegal profits made from car theft, extortion via ransomware or manipulation to lower charging fees pale in comparison to what can be made from stealing EV data. EVs track performance and record the surroundings using sensors and cameras, generating much more data than traditional vehicles. The data can tell us where to park, when an engine part needs replacement, and even how many pedestrians and/or vehicles are on a block. Even when not driving, EVs are still generating data that can be mined for profit, just as Big Tech companies such as Google and Meta make money from free services that enable access to user date.

Today, many companies profit legally by selling vehicle data, for example to identify open parking spaces or provide personalized location-based advertising. McKinsey & Company, a global consulting firm, estimated in 2016 that the worldwide revenue from car-generated data could reach $750 billion by 2030.[35]https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/automotive-and-assembly/our-insights/monetizing-car-data

EV data unlocks tremendous potential to improve driving safety, as well as producing municipal (traffic and parking space information) and commercial benefits. Automotive companies collect data to help drivers manage daily tasks with a few clicks or voice commands and, as noted above, make money by analyzing driver patterns and selling the information to advertisers. However, many EVs integrate third-party apps such as Amazon’s Alexa, Google Assistant and Apple’s Siri to facilitate voice calls and control home security while driving. Although convenient, third-party apps open security backdoors for hackers, providing access to the driver’s personal information, as well as data directly associated with the driving experience. Phone contacts can be extracted from connected apps, and credit card details can be obtained through the dashcam. Further, with the help of car data, hackers can profile the driver via the data as a new form of espionage and use it for extortion, stalking or other criminal purposes.[36]https://venturebeat.com/2022/05/15/car-hack-attacks-its-about-data-theft-not-demolition/

The new infrastructure law calls for the installation of monitors for alcohol, impaired driving and child alerts. This promises to significantly reduce fatalities caused by drunk drivers, for example, which accounted for 11,654 deaths in 2020.[37]https://www.responsibility.org/alcohol-statistics/drunk-driving-statistics/drunk-driving-fatality-statistics/ The monitors could also reduce the number of children dying from vehicular heatstroke, which total 917 since 1998 in the U.S.[38]https://www.noheatstroke.org/ Even so, privacy advocates fear that this data might be very compromising if the information is inadvertently leaked or hacked.[39]http://www.aclu.org/news/privacy-technology/congressional-drunk-driver-detection-mandate-raises-privacy-questions

Policy Decisions: Way Forward

EVs are a storehouse of private data, collected constantly by a myriad of sensors, which makes EVs vulnerable to cyberattacks.[40]https://upstream.auto/blog/the-hidden-cyber-risks-of-electric-vehicles/ To counter this, robust online patch management is essential for handling installation errors.[41]http://www.tesla.com/support/software-updates

Sometimes servicemen or owners download a patch from the dealership website onto a computer, transfer it onto a thumb drive and stick it into a USB dongle port in the car. Making manual software updates[42]http://www.forbes.com/sites/thomasbrewster/2015/01/15/researcher-says-progressive-insurance-dongle-totally-insecure should be avoided since the updates might be compromised[43]https://securityboulevard.com/2021/03/patch-management-in-the-post-solarwinds-era/ or additional malicious files might trigger malware when connected. Further, there should be a proper patch integrity verification mechanism installed in the vehicle that validates the updates before installation.

Also, as shown by the “TBONE” attack on Teslas in 2021, which used a drone to penetrate the EV’s control system, automakers should avoid using hardcoded (also termed, embedded) credentials inside the vehicle.[44]https://www.thedrive.com/tech/40438/researchers-used-a-drone-and-a-wifi-dongle-to-break-into-a-tesla Such information can easily be retrieved through eavesdropping or by malware infiltrating the system. Credentials should be stored in a configuration file or a database in encrypted form, and policies should be established for enforcing their rotation and ensuring their complexity.

Since 2011, there has been a significant increase in EV charging infrastructure,[45]https://afdc.energy.gov/fuels/electricity_infrastructure_trends.html as EVs gain popularity. During the same period, the number of EVs in the U.S. increased from 16,000 to two million. However, although EVs account for 19 percent of new car sales in Europe in 2021 and 15 percent in Mainland China, they account for only 4 percent in the U.S.[46]https://www.canalys.com/newsroom/global-electric-vehicle-market-2021?ctid=2627-70a8050e26f41f72baaf6b38e200993a

To scale up securely, a mechanism is needed for physical security checks before the issuance of a permit from the federal government to install a charging station, and only compliant hardware should be allowed.[47]https://techcrunch.com/2021/08/03/security-flaws-found-in-popular-ev-chargers/ Several popular chargers have used cheap motherboards with insecure design, such as the Raspberry Pi, which has limited support for secure booting; signed firmware, which guarantees security; key storage; hardware encryption; USB port locks; and tamper resistance. Further, a mechanism for data security should be clearly articulated in the permit request form.[48]https://afdc.energy.gov/files/pdfs/EV_charging_template.pdf Recently, the U.K. approved comprehensive EV legislation that includes security requirements, which will be implemented nationally in December.[49]https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/electric-vehicle-smart-charging

Auto insurance providers cover vehicle accidents and personal liability. It would be helpful to consumers to add provision for cyberattacks.[50]http://www.insurancebusinessmag.com/us/news/cyber/electric-vehicle-cybersecurity-business-owners-worried-about-the-risks-398832.aspx Automotive companies should clearly define the classifications of vehicular data, based on sensitivity, to determine the appropriate sharing and processing procedures. Lastly, to help consumers purchase the most appropriate vehicle and to provide a competitive market environment regarding cybersecurity features, it is important to create a system for cybersecurity ratings in vehicle consumer reports.

The automotive industry should define, create and implement a proper mechanism for remote inspection of customers’ vehicles to identify malware and other stealth attacks on EVs and the charging infrastructure. Further, clear policies are required to educate users on the methods and safeguards for dealing with ransomware attacks.

As the EV network matures into a large cyber-physical system, there should be no weak links that can hamper the building of the half-million charging stations nationwide.

Asad Waqar Malik

Asad Waqar Malik, PhD, currently works as a postdoctoral scholar at NDSU’s Department of Computer Science. He also serves as an Associate Professor at the School of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science at the National University of Sciences and Technology (NUST) in Pakistan. He earned a PhD in parallel and distributed simulation/systems at NUST. Prof. Malik’s primary areas of interest include distributed simulation, cloud/fog computing, autonomous vehicles and the Internet of Things, with a focus on security.

Zahid Anwar

Zahid Anwar, PhD, serves as Associate Professor of Cybersecurity in the Department of Computer Scienceand a scholar at the Challey Institute for Global Innovation and Growth at NDSU. He earned an MS and PhD in Computer Science at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, and he conducted postgraduate research at Concordia University. Previously, Prof. Anwar served on the faculties of the National University of Sciences and Technology in Pakistan, the University of North Carolina at Charlotte and Fontbonne University.He has also worked as a software engineer at IBM, Intel, Motorola, the National Center for Supercomputing Applications, xFlow Research and at CERN on various projects related to information security and data analytics.Prof. Anwar’s research focuses on cybersecurity policy and innovative cyber defense. He is a CompTIA certifiedpenetration tester, security+ professional and an AWS certified cloud solutions architect.

References