Since the 17th century, newspapers have functioned as important sources of information for historians. Beginning in the mid-19th century, photographs became another crucial primary source. Both newspapers and photographs—in publications and taken by the public—provide valuable insights into past events as they happened, as well as chronicle our ever- changing culture and society.

Ironically, and tragically, digitization in recent decades has both greatly increased the number of photographs taken and news sources available online, but at the same time often sequestering them in a virtual black hole. Personal photos are password protected and stored mostly in the Cloud, to which access is restricted. Local print newspapers have declined greatly in number nationwide, especially between the coasts. Online news sources, in contrast, are usually not oriented to specific geographic communities but to increasingly specific interests and polarizing worldviews. Much less attention is given to what happens here and now, especially in rural areas. As well, online news content is stored in the Cloud, and much is behind paywalls. Nor, typically, are the publications’ archives available. If 30 photos were taken for a story, for example, only a few are published online and at low resolution.

Photographs as History’s Sources

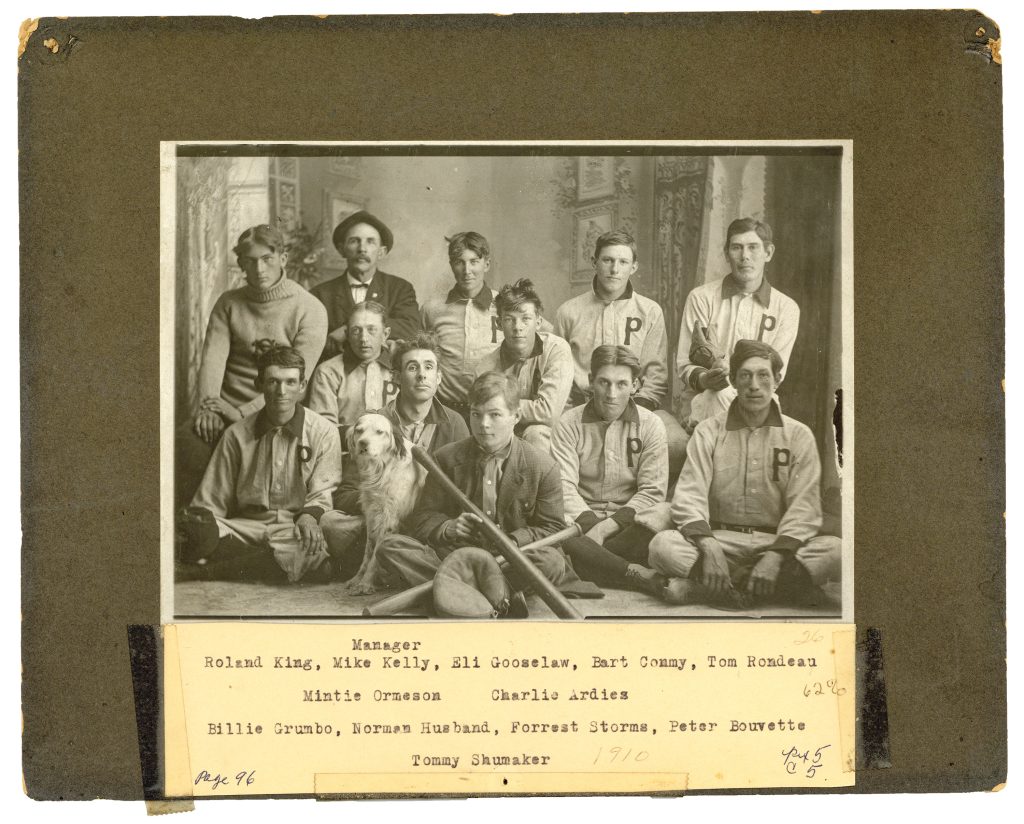

State historical societies nationwide contain massive quantities of photographs. The State Historical Society of North Dakota holds 2.1 million photos, while peer institutions in Montana and Wisconsin contain 500,000 and three million photos, respectively. The same is true for repositories worldwide, including private collections and university libraries and archives. These photographs document everything from the everyday and mundane—daily living, natural landscapes—to the dramatic and newsworthy.

Newspapers as Historical Sources

Newspapers serve as both primary and secondary sources for historians and researchers, as well as journalists and authors. Sometimes called the “first draft of history,” newspapers contain stories of local, state and national events as seen by contemporaries and sometimes colored by the attitudes prevalent at the time. No other single source provides as much historical information about communities as local newspapers. Newspapers also document the acts and lives of individuals, making them one of the main sources of information for genealogists as well.

Photography’s Darker Room

Many photos in archives and libraries were once part of personal collections. Then as now, people photographed important life events, including birthdays, vacations, graduations and weddings. Prior to the iPhone age, most families stored their pictures in photo albums or kept drawers full of photos. These memory collections were handed from one generation to the next, and families, business and even agencies brought photographs and negatives to various archives.

Archivists, librarians and historians then determined how and if this material fit into the historical record, and whether or not it seemed useful to future historians and researchers. People invested significant effort, money and time in daguerreotypes, tin types, glass plate negatives, modern slides and prints over the last two centuries, and so attached considerable value to these objects.

Since the introduction of the iPhone and other smartphones, film developing declined almost to zero today. People still take photographs, in fact, more than previously. Currently, 1.81 trillion photos are taken worldwide per year (or 54,000 per second), and this is projected to increase to 2.3 trillion by 2030. These are overwhelmingly digital, and 93 percent are taken on smartphones.i

However, relatively few are printed and, instead, often downloaded to a computer, floppy discs, CDs, DVDs and various types of removable hard drives. But these are fragile and mostly password protected. Many digital photos are discarded, or due to increased memory, left on cellphones and then lost when the cellphones are discarded. Or photos are transferred to social media and, again, are password protected. Today’s photographs are born digital and remain so.ii

As a result, digital photos are not easily retrieved, as well as less likely to be delivered to local, state or national archives or other repositories. Imagine discovering a trove of digital devices, presumably containing photos, left behind by a deceased relative. If the passwords are unknown, the devices will likely be tossed. Yes, there are companies that can access the stored data, but how often will there be a compelling reason to pay for such services? Or how many children, grandchildren or friends will comb through CDs and DVDs, which are used rarely now? Few people have the hardware to read these items.

Kamal Munir, Professor of Strategy and Policy at the University of Cambridge, sums up the changing nature of photography in his analysis of Kodak’s history. Entering the digital age, Kodak, “having played such a central role in creating meaning for photography … failed to believe that meaning had changed, from memories on paper to transient images shared by email or on Facebook.”iii

Newspapers Unprinting

The State Historical Society holds the earliest published newspaper in what would become North Dakota: beginning with Fort Union’s Frontier Scout, first published in 1864, and including nearly all newspaper published since then, in print and online. Fortunately, in 1905, the state legislature passed the North Dakota Newspaper Law, requiring all official newspapers statewide to provide copies to the State Historical Society. The law’s value was demonstrated during the 1997 Red River Valley flood, when the Grand Forks Herald’s newspaper archive was destroyed by fire in the downtown fire.

Some states have similar legislation, but many do not. In Washington State, for example, the state librarian is required to preserve newspapers since they serve as a “valuable historical record for scholarly, personal, and commercial reference and circulation.” However, publishers are not required to send or transfer newspapers to the state librarian.iv Some states, in contrast, such as Kentucky and Georgia, have no laws regarding newspaper preservation.v vi

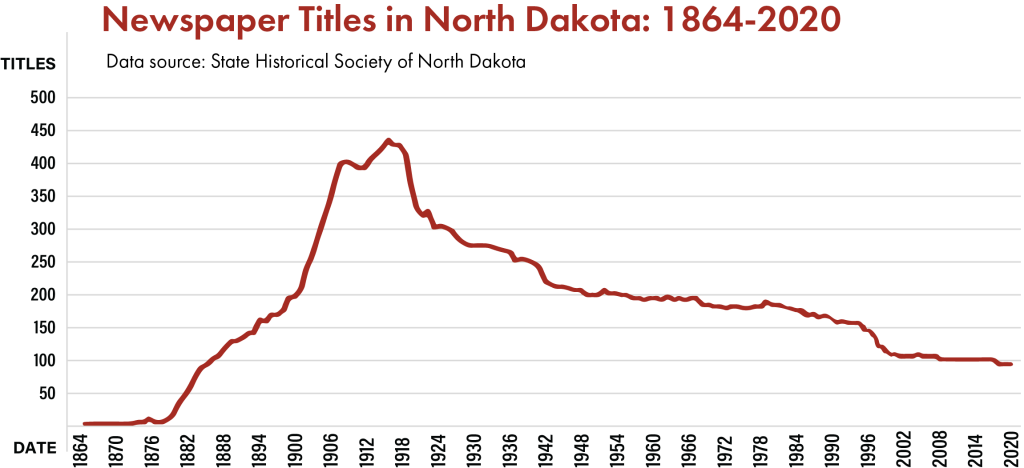

When internet use became widespread in the 1990s, newspapers began losing advertising revenue, which pressured many venues to shutter or publish exclusively online. At the peak of newspaper production in North Dakota in 1917, publishers produced nearly 430 newspapers statewide. Today, 74 survive.vii According to the North Dakota Newspaper Association, 64 weekly newspapers still print every issue. There remain 10 multiday newspapers, which publish a mix of paper and digital issues. This includes the newspapers from Bismarck, Minot, Devils Lake, Wahpeton, Williston, Valley City, Grand Forks, Fargo, Jamestown and Dickinson.

The total circulation of U.S. daily newspapers peaked in 1984 at 41.1 million and then declined to 24.3 million by 2020, at the same time as the nation’s population increased by 42 percent to 336 million.

Samuel G. Freedman, an acclaimed author and journalism professor at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, lamented this nationwide phenomenon in “Losing our Local Newspapers in the Digital Age,” published in Dakota Digital Review in January 2021. Not only has there been a precipitous drop in the number of newspapers, but the character of ownership deeply affects journalistic integrity. Previously, newspapers were typically owned by families that “felt it important to keep such papers thoroughly staffed and realistically budgeted as a public service. The new wave of newspaper owners are hedge funds, pension funds and similarly passive investors … demanding profit margins that can only be sustained by rounds of budget cuts, mostly meaning layoffs of staff and reductions in coverage.”viii Newspapers now often reflect their communities less accurately and so have become less valuable as historical records, even where they survive.

When newspapers were local, communities and state historical societies had better access to photo collections. Access has diminished with both shutterings and purchases by large corporations, one of which, for example, owns more than 100 newspapers, in 43 states, all behind paywalls. Large national and international businesses typically invest less attention and resources in local organizations, including libraries and archives.

Other Sources Dimming

Other primary historical sources are falling into darkness too. TV, print and online news reporters now record images and footage on digital cameras or cellphones. Story text is emailed to editors with no physical copy other than the journalist’s initial handwritten notes. And these are becoming rarer as voice transcription and digital notetaking devices improve and become more common.

Before digitization, newspapers stored full editions and clippings, filed alphabetically, along with photos and notes, including many unpublished images and information, in what was termed the “morgue.” Few publications still maintain morgues, instead digitizing their records. Custody of some of these collections has been given to public institutions, for example, as listed by the Library of Congress.ix But most major publications are missing. The New York Times still maintains its estimated 700,000 pounds of historical paper records alone, which researchers may access for $250 per hour—far beyond the reach of almost all writers, archivists and historians.x

As records are digitized and physical copies discarded, not only does access become a challenge but also long- term survivability. Digital storage space, especially for photos and videos, is expensive. How long will media companies pay for this service?

As well, digital content can be hacked and deleted or altered. A comprehensive electric grid failure could jeopardize all digital information. An electromagnetic pulse event (EMP) could disable the entire electrical grid, perhaps for years, denying access to digital records and transactions, and might wipe them out entirely. An EMP could be caused, as examples, by a nuclear attack or another Carrington event, which was an intense geomagnetic storm caused by a solar flare in 1859. Carrington-level events recur about every 150 years.xi

Preservation

This time in history is likely the most challenging yet for archivists. In the past 30 years, due to digitization, there’s been a decline in content shared with archives and historical societies. Further, the task of preserving digital materials permanently into the future is daunting. Not only is the preservation of images, videos, sound recordings and documents important, but also the preservation of the media on which the content is stored. Swift changes to technology produce obsolete file formats, hardware and software, presenting serious difficulties for archivists.

Lack of metadata in digital files causes more emptiness in the historical record. Metadata is crucial to preserving and accessing digital files, since it provides information related to the file’s content, structure, preservation and technical aspects. Descriptive metadata also provides details related to the content of the file: the who, what, where and when. This information proves quite useful to researchers. There has likely never been another time more documented than today, but what’s that documentation worth if it isn’t described or accessible in the future?

In terms of what digital preservation looks like to archives, many are still searching for the perfect answer. Archivists now must be adaptable to ever- changing technology. What works for today’s digital realm, might not work tomorrow. Implementation of digital repositories and preservation strategies is key to ensure the access of digital history in the future.

Many archives worldwide started keeping older technologies to ensure access to obsolete files and software. These computer museums provide both the hardware and software of the original file format. Other archives focus on emulation or migration as preservation strategies. Format migration is one of the most widely used strategies and involves migrating the file formats to new digital formats. Emulation utilizes current technologies to access original files while mimicking the original technologies that created and used the files.

Best described as a digital stack, in reference to the secure rows of physical storage found in libraries and archives, digital repositories provide long-term preservation, storage and access to digital resources. Key features to digital repositories include ingest steps, data management (preservation) and access methods.

Common steps at ingest include inventory, file format identification, checksum application and virus check. During preservation, files may undergo migration to stable formats and storage. Fixity checks to ensure no changes to the files should occur regularly at all stages of preservation. Technology creates easier and faster access to digital records. In digital repositories, descriptive metadata aids in the access of files. Digital repositories often provide direct access of content to researchers and historians, providing more content to more people. No doubt digital preservation will evolve with technology, and archivists certainly are ready for the task to adapt methods to capture, preserve and ensure access to the historical record, whether digital or paper.

Microfilm

Although it may seem like an outdated tool, archivists continue to utilize microfilm for preservation and access purposes, especially for materials presented on both paper and digital medias, such as newspapers. A light source is the only required piece of equipment to view microfilm; in contrast, digital files need hardware, software and preservation of bytes. In recent years, the use of microfilm to preserve the content of digital data has increased. Tools that convert digital files to microfilm, such as archive writers, allow archivists to place digital files onto preservation microfilm. The use of imaging technologies, such as overhead scanners and cameras, create the ability to capture the print issues of newspapers and integrate them with the born digital newspaper issues to form a complete run of the newspaper on microfilm in preservation and a digital, text-searchable access copy.

Active Collection

To meet current challenges, archivists are taking a more flexible and proactive approach to collecting materials and spreading awareness. Recent trends show that archivists are increasingly active in early stages of the records lifecycle to assist with developing systems and workflows to fuel long-term digital preservation. For example, archivists in North and South Dakota work with each state’s newspaper association to develop standards and procedures for the creation of digital newspapers ensuring easy transfer to state archives for preservation and future access.

Now as historic events unfold, archivists actively collect photographs and witness testimony from private donors to ensuring archival capture. Recently, after noticing a large gap and decline in collection material related to high school sporting events beginning in the 1980s, the North Dakota State Archives put out a call for photographs covering events that cover the past four decades. During the COVID-19 pandemic, many archives worldwide—including Johns Hopkins University Library, Hershey Community Archives, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries, Royal British Columbia Museum and State Archives of North Carolina—collected real-time accounts, (including digital stories, images and videos) of people’s experiences.

Active collection places the historical record directly into the hands of archivists to preserve for future generations. It also allows archivists to establish how the material is gathered, which helps to create sustainable formats with the proper descriptive metadata. Through actively collecting digital files, archivists can establish what information donors must submit with files for donation. Accompanying descriptive information, such as a caption, date and location, are common requirements for archives to accept digital files to ensure future use of the items. Receiving this information directly from the creator or donor provides an invaluable resource. Most often, the creator of the image can provide more complete descriptions, unlike archivists processing the materials who merely must describe the file to the best of their ability.

Education and outreach help archivists share the importance of active file management and digital preservation strategies, such as multiple copies, format and storage migration, and metadata. These instructions are important not only for business, organizations and government entities, but also individuals to raise awareness of the importance of private collections and family histories to the historical record.

Future Challenges

As archivists and historians improve securing and preserving digital content, they will have to contend with the growing challenge of mining the enormity of digital content and also determining what are authentic versus fake primary sources. While artificial intelligence (AI), with its acuity in pattern recognition, will help with both mining and authentication, AI will also increasingly be used to generate content in accelerating volume and create deep fake documents, photographs and videos that are extremely difficult to distinguish from real content.

Last May, a fake photo of an explosion near the Pentagon, seemingly generated by AI, circulated on social media causing stock markets to drop. This and other deep fakes motivated the major Big Tech companies developing AI, including Amazon, Google, Microsoft and Meta—to pledge they would watermark AI content to identify the work as AI-generated and by which AI service.xii

If you don’t know history, then you don’t know anything. You are a leaf that doesn’t know it is part of a tree.

— MICHAEL CRICHTON

In 1905, the state legislature passed the North Dakota Newspaper Law, requiring all official newspapers statewide to provide copies to the State Historical Society. The ND State Archives continues to microfilm all newspapers to ensure the preservation of and accessibility to yesterday’s stories.

Hopefully, this will soon be implemented. OpenAI, which developed ChatGPT, released an AI detection tool in January, designed to determine whether content had been created with generative AI. Six months later, OpenAI closed access to the tool since it proved inaccurate.xiii However, the need for authentication will ultimately be met, not merely in legislation and regulations, but in reality, or Big Tech with all its astounding applications will lose the public’s trust and much of its attention.

Of course, historians, archivists and librarians have found ways to chronicle events for millennia before digitization and AI—and under far more trying circumstances, such as war and persecution, than today. If past is prelude, current challenges will be met, and history’s looming digital black hole will ultimately be illuminated.

References

i “Number of Photos (2023): Statistics and Trends,” Phototutorial: https://photutorial.com/photos-statistics/ ii Katie Hafner, “Film Drop- Off Sites Fade Against Digital Camera,” New York Times, (October 9,2007): https//www.nytimes. com/2007/10/09/business/09film.html iii Cambridge University, Research News (March 14,2012): https://www.cam.ac.uk/research/news/the-rise-and-fall-of-kodaks-moment iv Schollmeyer, Shawn. (Washington Digital Newspaper Coordinator, Washington State Library), in discussion with author. June 9, 2023 v Summerlin, Donnie. (Digital Projects Archivist, University of Georgia Libraries), in discussion with author. June 9, 2023 vi Terry, Kopana. (Curator of Newspapers, University of Kentucky Libraries), in discussion with author. June 10, 2023. vii Helfrich, Beth (executive director, North Dakota Newspaper Association), in discussion with the author. May 10, 2023. viii Freedman, Samuel G. “Losing our Local Newspapers in the Digital Age,” Dakota Digital Review, (December 3, 2020). For a broader discussion on the effects of journalism in society see Howard Gardner, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, and William Damon, Good Work: Where Excellence and Ethics Meet (New York, Basic Books, 2001) 158-159. ix Newspaper Photograph Morgues in the United States and Canada, Library of Congress: https://guides.loc.gov/newspaper-photo-morgues x Young, Michelle. “Photos Inside the “Morgue” of the New York Times,” Untapped New York: https://untappedcities.com/2020/02/25/photos-inside-the-morgue-of-the-new-york-times/ xi Lloyd’s Atmospheric and Environmental Research, “Solar Storm Risk to the North American Electric Grid”: chrome-extension:// efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://assets.lloyds.com/assets/ pdf-solar-storm-risk-to-the-north-american-electric-grid/1/pdf-Solar-Storm-Risk-to-the-North-American-Electric-Grid.pdf xii Rivera, Gabriel. “How Can You Tell If an Image is AI-Generated? Soon, There’ll Likely Be a Watermark,” Insider, July 21, 2023: https://www.businessinsider.com/ai-tech-companies-biden-agree- watermark-identify-generated-content-images-2023-7?op=1 xiii Nelson, Jason, “OpenAI Quietly Shuts Down Its AI Detection Tool,” Decrypt, July 24, 2023: https://decrypt.co/149826/openai-quietly-shutters-its-ai-detection-tool

Bill Peterson, PhD.

Bill Peterson, PhD, is the Director of the State Historical Society of North Dakota (SHSND) and serves as the North Dakota State Historic Preservation Officer. He is responsible for the overall operation of the State Historical Society, which consists of more than 59 museums and historic sites across the state. Previously, Peterson was the Vice President of Collections and Education, and Northern Division director of the Arizona Historical Society. He earned a Bachelor of Science in U.S. History at Lake Superior State University, a Master of Historic Administration and Museum Studies at University of Kansas and a PhD in American Culture Studies at Bowling Green State University.

Lindsay Meidinger

Lindsay Meidinger is the Head of Archival Collections & Information Management for the State Historical Society of North Dakota (SHSND). Meidinger earned a Bachelor of Science from the University of Mary and a Master of Library and Information Science from San Jose State University. Since starting at SHSND in 2012, she has worked in archival outreach, and with collections featuring moving images, manuscripts and government records. In 2017, Meidinger became the first electronic records archivist for the state. Currently, she manages the organization, arrangement, description, preservation and access of the State Archives’ vast collections, both paper and digital. Meidinger maintains the State Archives’ collection management database and digital repository. Additionally, she serves on North Dakota’s State Historical Records Advisory Board (SHRAB), which promotes the preservation and access of records with enduring historic value throughout the state.