When Safer Than Average Human Drivers

Public opinions on technology run the gamut from the best, most exciting, progressive thing humans create to improve their lives and the world around them, to posing a threat to our species’ existence.

There is technology deserving that approbation, such as more effective cancer treatments, DNA testing kits and GPS guided tractors. We would not be too far out of line to say it is almost miraculous. However, other innovations fall on the opposite end of public opinion: Any device or application relying on artificial intelligence (AI) beckons demise via Arnold Schwarzenegger’s Terminator cyborg assassin.

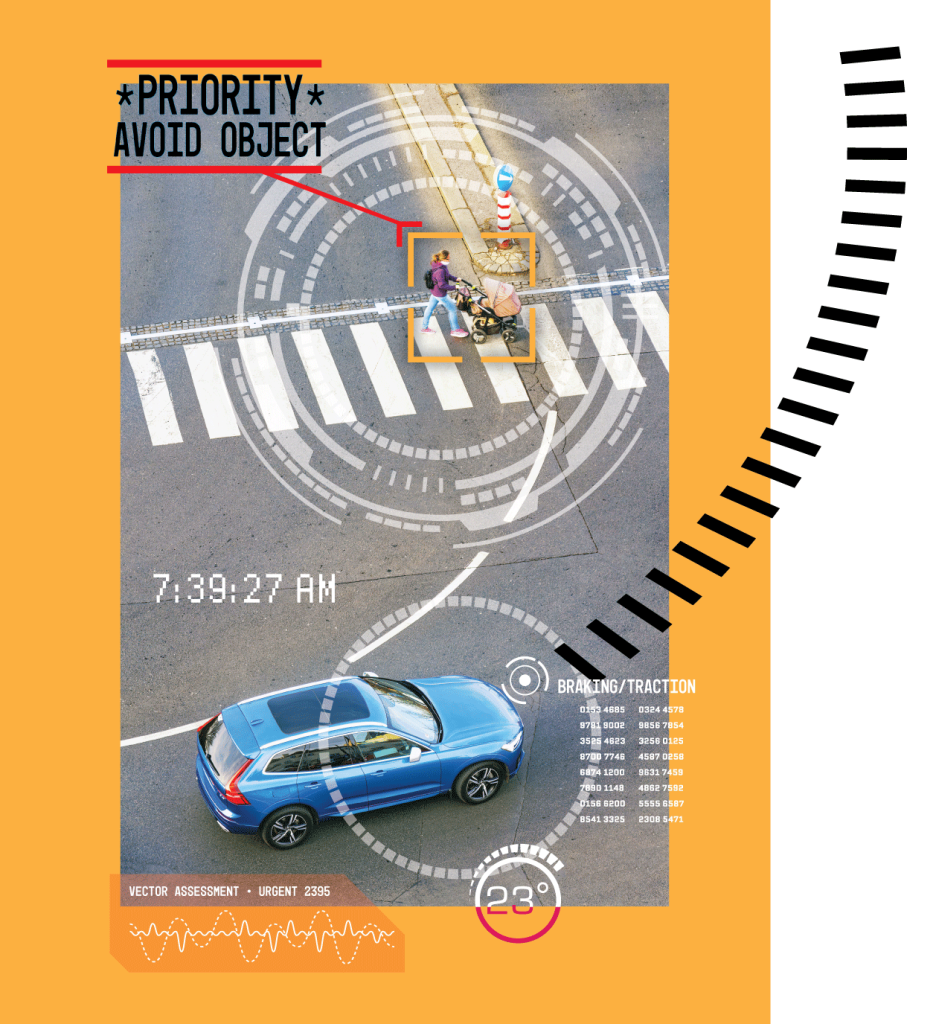

Certainly, there are dangers. “We are entering a time when technological evolution creates two new realms of socio-economic-technical activity: the Integrated Realm and the Machine-Robotic Realm,” Mark Hagerott, PhD, the Chancellor of the North Dakota University System and a technology expert, told my NDSU students in a talk this spring. (Please refer to the illustration on page 42.) “The capacity of AI/autonomous machines (robots) and cyberspace (the metaverse) to create wealth and power is enormous. But this technology has near unlimited power to impinge on the sanctity of human space, a possibility once protected against by the physical frontier of technology.”

With digitization, there are now three interlocking realms of activity on our planet: (i) Human-Natural, (ii) Machine-Robotic (near or fully autonomous intelligent robots) and (iii) Cyber-Metaverse (non-tactile internet including the Cloud). Increasingly, AI (and potentially artificial general intelligence [AGI]) is taking control of realms (ii) and (iii) and the convergence of all three, as well as threatening to usurp most of the Human-Natural realm. This graphic illustrates the challenge and urgency of limiting the reach of AI to reduce cyberattacks and long-term human deskilling.

Yet in the real world, digital technologies are proving quite valuable tools for human use. For example. vehicles that reduce accidents by helping drivers stay in their lanes and otherwise make driving safer when drivers aren’t paying sufficient attention. People are glued to their phones and other devices, and GPS has become essential in some lives. As a result, attempts to reduce AI’s encroachment into research and the marketplace are likely to fail. AI is too convenient, helpful and profitable.

One major question is whether the most beneficial AI technologies, such as using self-driving vehicles (which are not necessarily electrical), should become a duty rather than merely an option. If there is a duty to use them, then is there a corresponding obligation to create them?

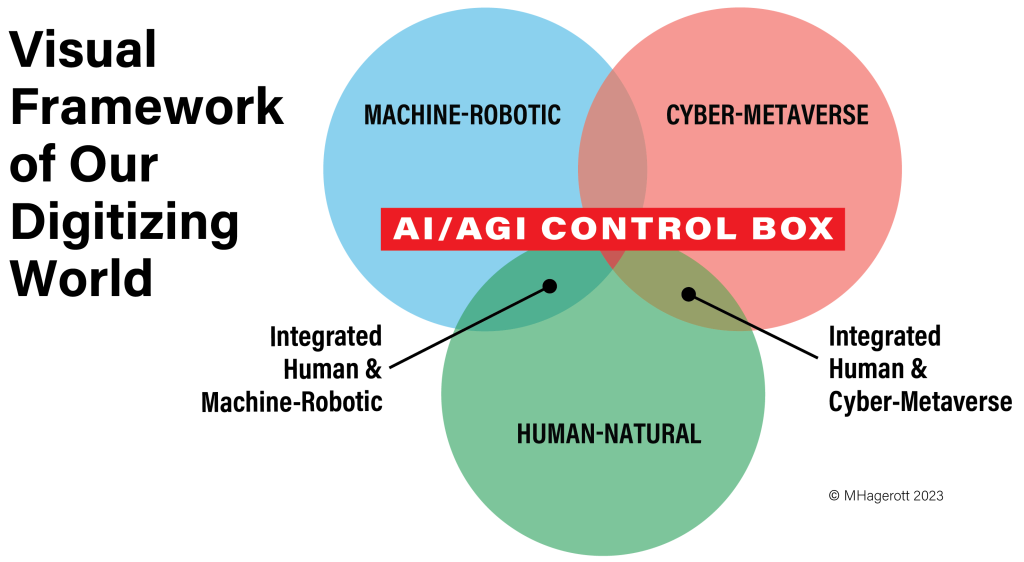

An example of human lives with too little “Human-Natural” and too much “Machine-Robotic” and “Cyber Space,” as illustrated in the 2008 film “Wall•E.”

Regarding self-driving vehicles, a 2022 study predicted that 94 percent of long-haul commercial trucking can be done by AI provided that the technology improves to handle all weather conditions.i If the study’s authors are correct, high turnover rates and the current shortage of 80,000 drivers can be mitigated if not eliminated. (Of course, the potential for significant job losses with AI adoption is an important and controversial topic, but beyond the focus of this article.) And let us not forget the potential safety improvements through devices that never tire or become distracted. If self-driving technology can work for truck driving, then there is no reason to believe it can’t work the same for long-haul car trips, or as a designated operator for the elderly, or for those with substance abuse or medical problems, or others at risk or risky drivers.

Granted that adopting technology is enticing, especially when it eliminates significant problems, ethical worries arise. A more significant one is technology’s impact on human beings in their lived environments. In particular, through AI, eroding human freedom in making decisions, which has negative impacts on autonomy, moral agency, and people’s abilities to be and do what they should. More simply, by replacing human decision-making with that of a program or machine, we make people less able to make autonomous choices for themselves and therefore infantilize them rather than empower them. If this is part of a slippery slope argument, then we could very well end up producing the rotund, apathetic human survivors encountered in the film “Wall٠E.”

Argument for a Mandate

Freedom and free will are two of the most valued human powers because they are essential to us being moral agents in the first place. To limit either, therefore, has to be justified with far stronger evidence than merely defending why people are entitled to exercise them, and then letting the social marketplace sort it out. To propose limiting freedom and free will, such as having a duty to buy and use a self-driving car, demands even more justification. This is in fact an extraordinary claim requiring extraordinary evidence.

Deciding if there is a duty to do something, furthermore, requires a higher standard than merely proving that an action is morally permissible or right. Duties entail that failure to perform them is automatically forbidden and wrong, unlike an act being morally right, which might mean it is one of many morally right actions. The difference here is between it being permissible to buy a self-driving car versus a standard vehicle, and the moral (not legal) mandate that only a self-driving car will fulfill one’s duty.

Many moral factors are at stake in deciding if technology is permissible, much less obligatory. In engineering, there are five ethical factors that help decide when a risk is morally acceptable, which also can address when technology is permissible or required:

- The degree of informed consent with the risk,

- The degree to which the risk is voluntarily accepted,

- The degree to which the benefits of a risky activity weigh up against the disadvantages and risks,

- The availability of alternatives with a lower risk, and

- The degree to which risks and advantages are justly distributed.ii

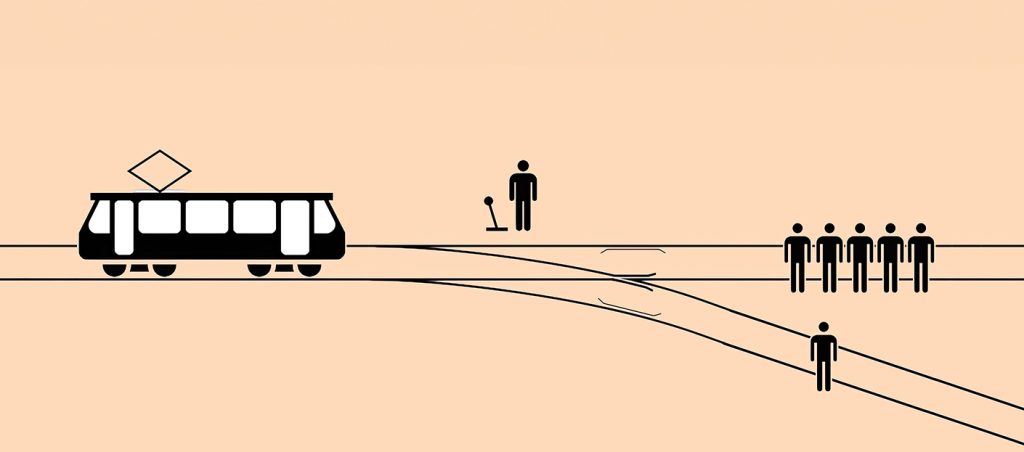

The Trolley Problem: You have to decide whether to pull the switch next to you to send the runaway trolley down the new track to kill one person or allow the trolley to remain on course to kill five people. Do you pull the switch? Most people will pull the switch to save five people by sacrificing one. Illustration / Zapyon

For the first two, above, freedom and free will entail that if people understand the risk to themselves and still decides to engage, then their decision should be deferred to. They have the right to make that decision and also the responsibility for the consequences, good or bad. On the other hand, imposing hazard on others without their knowledge or consent is generally impermissible because this does not respect their free-will agency. The third criterion is merely a cost-benefit analysis that the technology has to be worth the cost, whereas the fourth factor states the common-sense view that any option, which gets us where we want to go without as much risk to self or others as the other alternatives open to us at that time, is the only rational option to pursue. The final factor concerns justice: We should not impose greater risk on more vulnerable members and groups of our population, especially if the rewards are not sufficiently shared with them. The unfairness becomes greater if the vulnerable are the only ones to bear the costs, while the privileged receive all the benefits.

Given these moral factors, when can a moral agent be obligated to use technology? When the risk of not doing so is so great that it must be mitigated or eliminated. More precisely, the person must use the technology if all of the following five conditions are met. Firstly, if adopting the technology significantly lowers the risks involuntarily imposed on others and in which the risks for severe harm to either the agent doing the action or those affected by it are high. The third through fifth requirements are that there isn’t a considerably better alternative that achieves the desirable outcomes more efficiently and through which the risks are significantly more equitably distributed, while at the same time the technology does not burden the agent to an excessive degree.

The Technology

Most AI implementation begins with the basics of rational decision-making for actions: Values and other relevant factors are the construction material, and principles are the tools to put the material together in various, approved ways. Once identified through theoretical problems, such as Trolley Problems, some decision procedures, with carefully delineated steps to build a solution, are programmed. The goal here is for AI to identify the rules and relevant information, and then manipulate them successfully to show at least a nodding acquaintance with how humans make decisions and work.

Of course, at the moment, the reliability of driverless cars is far below what is required to make them a less risky alternative to normal driving on average. That means that before autonomous driving systems could replace all human drivers, they must be able to reduce travel risks to a level significantly below that of the average driver for that population demographic. Moreover, this technology would have to be acceptable to the general community, based on the criteria above.

One general standard is that the technology has to be safer than the average human driver, according to Michael A. Nees.iii It is hard to understand what this requirement actually means in practice because most people believe themselves to a better driver than the average. So, is the standard really about being better than the average human driver or something much higher?

That seems to be the case in a survey on driverless cars, conducted by the City, University of London (CITU).iv Sixty-one percent of respondents said the technology and cars would have to be much safer than the safest human driver or the standard increased to never causing a serious collision. People don’t trust self-driving technology: Only 18 percent said they were comfortable with autonomous cars on the road as long as they are as safe as the average human driver. It, therefore, might be best to concentrate on drivers who are more at risk than the average driver and merely use the average driver as our measure for self-driving car technology’s permissibility.

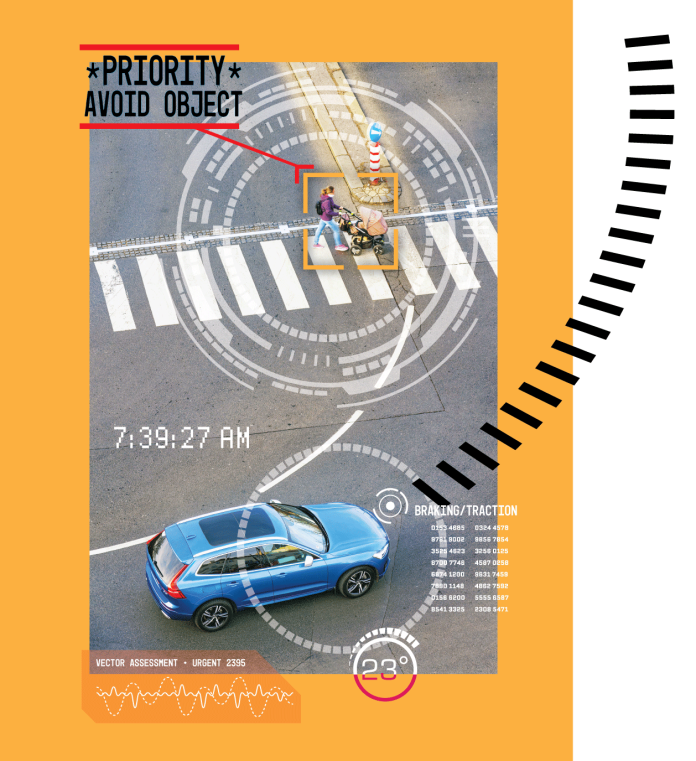

AI in motor vehicles makes sense when it reduces accidents by augmenting human driving, such as the stay-in-one’s-lane technology. Depending on the situation, it may or may not be essential to adopt these safety features. The case for a duty grows stronger when the technology becomes the only reasonable travel option for a driver with medical or other issues that greatly increase risk on the road. Drunk drivers, many elderly and people with some medical conditions move the risk from that faced in normal driving conditions with normal drivers to a far higher qualitative and quantitative degree.

Furthermore, there is an opportunity benefit to those who cannot drive because of some medical conditions or other pressing problem: They have the freedom to have a car dedicated to their needs and decisions rather than having to rely upon public transport or other people’s schedules. This ability to do what one needs or wants to do is liberating by giving people control over some of the basic activities taken for granted in a car-centric society, especially in rural states where there is no public transportation, or it can be an imposition to ask neighbors and family.

AI’s Threat

“Man is born free and everywhere he is in chains,” wrote Jean-Jacques Rousseau in The Social Contract,v aptly capturing humanity’s current condition, especially in the industrialized world with its dependence on its technology. Most of us feel incomplete, for instance, without constantly checking our smartphones to see if there is an email, text or some oddly interesting new posting on social media. We are lost without access to the digital world because it is essential to being able to function and thrive in our technology dependent society.

Technology is supposed to liberate us from repetitive drudgery to do more interesting things, but it can end up doing the opposite. Technological determinism, a sociological term for the fatalistic surrender to technology, binds us to a world that is determined by technology rather than our lives being under our meaningful control. Something like this was predicted by Martin Heidegger in “The Question Concerning Technology.” There he writes that while technology has no inherent moral value, the way humans approach crafting the world in which they live as a response to technology makes it conditionally good or bad.vi The problem, he says is the way humans have myopically adopted technological thinking—calculative reasoning—as the only form of thought. This in turn has caused us to begin seeing people and all things in the universe as mechanical objects rather than for what they truly are.

This mechanistic, mental framework leads us into inauthentic instead of the authentic existence, which everyone naturally seeks. Instead of having an existence filled with wonder and amazement, the result is the “I” of the individual grasping his true Being is sacrificed to the “they” mentality in which the focus is on objects outside of who we really are. In other words, we fatalistically allow technology to rob us of our freedom to make our lives meaningful, rather than using it for the tool it was intended to be to improve lives.

Humans, moreover, are social animals, who learn what it is to be human through interactions with others and making their own decisions about those interactions. We could say that people are the result of evolutionary adaptations in which those better able to compete and collaborate in an environment tended to survive and reproduce, thereby passing their genes on to future generations. Part of what made our ancestors better contenders was the ability to make the right decision in the situations they encountered, especially risky ones. Better choosers of the right thing survived, while slower ones became lunch for predators or otherwise had truncated lives. So, it could be reasonably claimed that to be human requires that we make choices for ourselves as individuals, without forgetting that those selections are being performed in collaboration with the other people in our society. Accordingly, although there might be explicit interactions and planning, we can manage driving a vehicle in crowded traffic, walk in a crowd or socially interact with strangers without mishap. To be human, therefore, is to be constantly engaged in decision-making with or without interacting with others.

Self-driving cars and other technology can diminish the quality and quantity of this constant choice-making and eventually enslave people depending upon what the technology actually does. The Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) makes a distinction between levels of automation for self-driving vehicles, which usefully shows when the technology is operating as the tool to assist and when it can lead to infantilizing humans:

- Cars with some driver’s assistance, such as cruise control and lane change monitoring and warnings.

- Car with advanced cruise control or an autopilot system that can take safety actions, such as braking.

- Cars requiring a human driver but able to perform some safety critical functions, such as steering and braking at the same time, in certain conditions.

- Cars capable of self-driving most of the time without input from the human driver, but which might be programmed not to drive in unmapped areas in severe weather.

- Cars with full automation in all conditions.

Tesla vehicles come equipped with the most advanced autonomous hardware and software, including enormous processing power, precise GPS, multiple cameras providing a 360-degree view, ultrasonic sensors and now radar to help navigate, especially in bad weather. According to CEO Elon Musk, Teslas configured with Hardware 3, which was first released in 2019, will have full self-driving capability surpassing human safety levels. Hardware 4, which upgrades the onboard computer and sensors, was released for new vehicles in early 2023. However, Tesla’s Autopilot (not yet fully autonomous) has been involved in 736 crashes since 2019, including 17 deaths. Many improvements need to be made before fully autonomous driving vehicles can be deployed safely. Photograph / Wikimedia

In San Francisco, a self-driving car operated by Cruise, owned by General Motors, ran over a woman after she was knocked in front of it by a hit-and-run driver. The Cruise AV severely injured the pedestrian, and firefighters arrived to find her pinned underneath the vehicle. Firefighters contacted the Cruise control center to make sure the vehicle was securely stopped and then used heavy rescue tools to lift it and pull the woman out, fire department officials said in a press release. In August, California authorities expanded driverless taxi services in San Francisco, giving the go-ahead for Waymo and Cruise operators to compete with ride-share services and cabs. The California Public Utilities Commission voted to let Waymo, a unit of Google-parent Alphabet, and Cruise essentially run 24-hour robotaxi services in the city. Photograph / San Francisco Fire Department.

All technology performing at Levels 4 and 5 can over time—with enough reinforcement rewarding AI takeover of decision-making that achieves whatever is desired—render human beings no longer able to make their own decisions or make far less autonomous ones when the situation is complicated and the relevant information hard to discern. Instead of being free with their free-will faculty working appropriately, people become mere automatons run by the technology that was designed to enhance their existence. They surrender to technological determinism or worse, the Machine-Robotic Realm in which robots and AI make decisions for themselves and humanity. Elon Musk said that AI is an existential threat to human civilization,vii and at Levels 4 and 5, that might actually be the case. The general issue is that AI machines could destroy humanity merely because AI’s goal is given priority over everything else, including humanity’s existence as organisms and moral agents living in their natural and social environments.

Integrated Solution

In response, Hagerott contends that we as a species using technology in our natural and artificial environments have an obligation to reject technological determinism and the Machine-Robotic Realm.viii He argues that we should adopt the Integrated Realm framework, which establishes ethics, policies and law that preserve human command of machines. If we take respecting persons with freedom, free will and moral agency seriously, the Integrated Realm is morally required as the only realm that recognizes what human beings are and how they operate in the real world.

Besides being free and possessing free will, our consciousness is non-computational as Roger Penrose argues in Shadows of the Mind. That means it’s not the computational brain model’s orderly systems running orderly programs that can be duplicated in computer language code: “There must be more to human thinking than can ever be achieved by a computer, in the sense that we understand the term ‘computer’ today.”ix Consciousness and understanding, according to Penrose, can only be explained by figuring out the connection between the quantum and classical physics of how our brains and their components function. Computers today cannot do this since: “Intelligence cannot be present without understanding. No computer has any awareness of what it does.”x Making computers more and more powerful, with the ability to evolve their own code or perform innumerable Trolley Problem experiments to determine how human beings react in stressful choice situations, will not lead to AI that is conscious or able to make decisions as humans do.

Ethical codes are unique to human beings and essential in every area of social life. They reflect the values and processes that society uses to govern the existence of and interactions among individual citizens, groups and institutions, partly to keep the society functioning acceptably. Moral codes are merely specialized social ethical codes aimed at making community members act ethically. These codes tend to develop over time, not systematically, but rather as the need alteration is perceived. As novel, unforeseen situations arise, there is a tendency to add process rules on what professionals should be or do for future, morally similar occurrences. If something goes wrong, then great pains are taken to revise the code so that the misstep won’t recur.

Human morality/ethics doesn’t work the way logic does in computer programs, mostly because human beings are not designed, mechanical systems. Ethics and much human activity require people to understand and engage in human activity critically, creatively and emotionally. We qua reasonable, social animals are the products of evolution, socialization and self-directed development; hence, we are more like patchwork creatures in our thought processing than we are finely tuned machines. Reason has a necessary role, we all agree, but emotion/feeling is its essential partner. Moreover, morality inherently incorporates imagination and creativity. When we think about what we should do or be, then we are thinking about worlds that may or may not exist. If they exist, then we ask ourselves if they ought to continue doing so. It took creativity to imagine a world without slavery or one in which women are equal to men, and then to dream how to achieve such result. While using identified moral rules as tools is essential to learning about ethics, something more is necessary to be a moral agent, which AI cannot duplicate.xi

Consider the following study on self-driving vehicles that shows the inherent need for humanity and morality in driving: The CITU study, cited above, showed that 91 percent of respondents said that being considerate to other road users (including drivers) is as important as following the formal rules of the road, and 77 percent agreed that drivers sometimes have to use common sense instead of just following the highway code to be able to drive appropriately. What these responses show is that driving and all other human endeavors require imagination. Perhaps less emotionally compelling is that it takes imagination to see when the rules do not apply and come up with an acceptable alternative. Being a moral agent and driver requires us to be good critical and creative thinkers. It requires emotive connection, including empathy and compassion. In conjunction with ethical theory, principles and values, which are a rational part of ethics, we as human, moral agents have a fuller Penrosian understanding of what ethics are and how they work in our decision-making than does any current AI technology. And possibly we will have more than any future AI technology can duplicate.

At the same time, autonomous vehicles have cameras, radar, light detection and ranging sensors that exceed humans’ ability to perceive, which help the vehicles navigate better in foggy or darker driving conditions. So, to get the best of both people and self-driving transport, a balance needs to be struck between when humans have control and in what way, and when to cede control to AI and technology.

The Integrated Realm framework uses the strengths of people and AI while trying to minimize their weaknesses. Caitlin Delohertyxii writes that AI lacks cognition—the human ability to use common sense, intuition, previous experience and learning to make split-second decisions—which makes human beings superior drivers. At the same time, autonomous vehicles have cameras, radar, light detection and ranging sensors that exceed humans’ ability to perceive, which help the vehicles navigate better in foggy or darker driving conditions. So, to get the best of both people and self-driving transport, a balance needs to be struck between when humans have control and in what way, and when to cede control to AI and technology.

SAE’s Levels 1 to 3 technology, explained above, is permissible to use and could be morally obligatory in some cases. These mechanical or digital devices augment what people are doing when driving and free some of their attention for more meaningful tasks, such as paying greater attention to the road, driving conditions and other relevant factors not being addressed by the technology. They do not replace human decision-making or the ability of humans to choose wisely. Psychologically as moral agents, we need to develop the brain’s executive function through experience, according to “The Adolescent Brain.”xiii Executive function exerts inhibitory control and includes working memory, which is the ability to keep information and rules in mind while performing mental tasks. Inhibitory control is the ability to halt automatic impulses and focus on the problem at hand. For example, running a meeting in a different way or taking a new, rather than habitual, route to work involves both inhibitory control and working memory. Doing things in new ways requires that people are in charge of identifying what matters, make decisions and plans to carry out their decisions, and then implement them. All of that is driven by executive function.

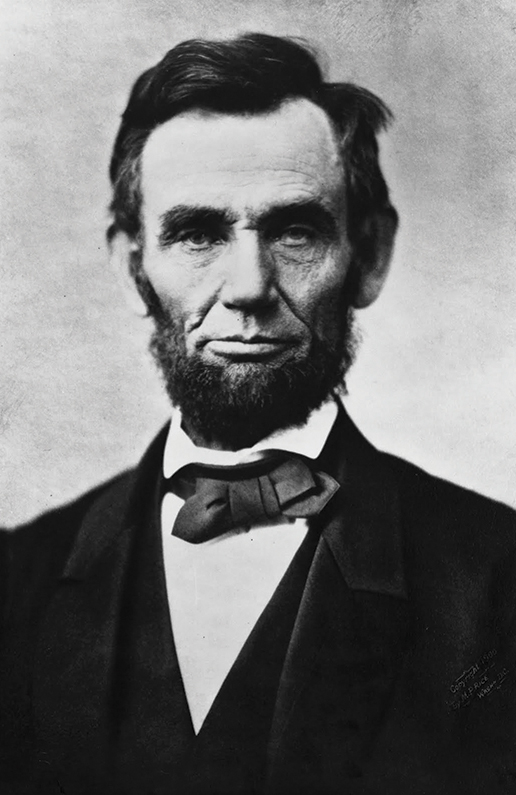

“Freedom is not the right to do what we want, but what we ought.”

Abraham Lincoln

A Moral Mandate?

Self-driving cars and other related technologies become mandatory for different reasons at the five levels. For SAE’s automation Levels 1 to 5, it is merely permissible for average drivers, or within the standard deviation of being so, to use the various technologies or not. For the first three levels, it would be a good idea to drive with these technologies in order to keep the drivers’ executive function higher and ego depletion lower for more important matters that may arise during a trip. Levels 4 and 5, on the other hand, pose more safety risks than the others if they begin infantilize drivers by making them less able to think quickly, creatively, critically or pragmatically while in the vehicle or in the driver’s other life experiences. But as long as these normal drivers retain the skills that make them human and thrive, the technology here is permitted but not required.

Levels 1 to 5 become more likely to be mandatory for those who have impairments that make their driving riskier than for the average driver. How to determine whether there is a duty to use the technology for these groups of drivers depends on five criteria (A through E) identified on page 52, above.

The first three SAE levels of automation could be required for new drivers who need experience to eventually become average enough to no longer need the technological training wheels. Consider that younger or other new drivers are at far greater risk of a motor vehicle crash than others. Males 16 to 19 years of age, for example, are three times more likely to have an accident than female peers. Also, when teenagers drive with other teens or young adult passengers, the chances of an accident increase greatly. Most of the heightened risks stem from inexperience and distractions while driving, according to the 2020 National Automobile Safety Administration report. These drivers need to learn how to drive while using the technology that makes them far safer.

On the other hand, for these drivers, the last two levels would be destructive to their learning how to drive, since they would always basically be passengers, or even worse, in the case of Level 4 made to drive in the worst possible conditions when their skill sets are not up to par. Since we want these drivers to learn to drive and improve their decision-making skills, Levels 4 and 5 cannot be required, unless in very unusual circumstances, such as those below.

SAE’s Levels 4 and 5 would be mandatory for only a small slice of the population, including drivers with physical or mental health or other risk-increasing conditions, according to their levels of inability. Someone who is blind would need a Level-5 vehicle. Drivers who have shown repeated refusal not to drink and drive might require a Level-5 vehicle to transport them, whereas those less incorrigible could make do at Level 4 technology. The desirable outcomes achieved by levels 4 and 5 technology enable people with these challenges to have meaningful functionality in a car-dominated society and the ability to make their lives authentic through decision-making, while reducing potential harm to others. Finally, mandating Level 4 and 5 technology for these groups of citizens places the benefits and burdens where they justly should go, at the same time making the world a better place. In other words, it creates a moral, meaningful Integrated Realm.

Future Moral Dilemma?

At this time, there is an obligation to have self-driving vehicles if the duty involves augmenting people’s ability to live authentically, but impermissible if this obligation leads to illicitly reducing or eliminating those opportunities. That duty opens the door, however, to thinking about whether improving autonomous cars to be superior by a morally significant amount over the average human driver at avoiding injuries and preserving human life would entail that average drivers have to use Level 5 self-driving vehicles. If the U.S. Department of Transportation and the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration are correct that almost 94 percent of accidents nationwide occur due to human error, then on similar grounds as mandating seatbelt use or pegging the drinking age at 21, would freedom and free will lose out to the goods of risk reduction, injuries avoided and lives saved? But that is a different, disturbing argument for a different time, although given the technological progress to date, it should be made sooner rather than later. ◙

References

i Mohan, A., Vaishnav, P. Impact of automation on long-haul trucking operator-hours in the United States. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 9, 82 (2022). https://www.nature.com/articles/s41599-022-01103-w

ii Criteria 1 and 3-5 are found in Van de Poel, I, Royakkers, L. Ethics, Technology, and Engineering. Maden: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011: 244. Criterion 2 is my addition.

iii Nees, M.A. Safer than the average human driver (who is less safe than me)? Examining a popular safety benchmark for self-driving cars. Journal of Safety Research, 69 (2019): 61-68.

iv Tennant, C, Stares, S., Vucevic, S., Stilgoe, J. Driverless Futures? A survey of UK public attitudes. May 2022. https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/29209/1/%20DF-uk-report-final-09-05.pdf

v Rousseau, J-J. The Social Contract. London: Swan Sonnenschein & Co., 1895.

vi Heidegger, M. The Question Concerning Technology and Other Essays. New York: Garland Publishing, Inc, 1977, https://monoskop.org/images/4/44/ Heidegger_Martin_The_Question_Concerning_Technology_and_Other_ Essays. And Heidegger, Martin. 1962. Being and Time. John Macquarrie and Edward Robinson (Trans.) (Harper & Row: New York, NY).

vii Corfield, G. “‘Out of control’ AI is a threat to civilization, warns Elon Musk.” The Telegraph, 29 March 2023. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/business/2023/03/29/control-ai-threat-civilisation-warns-elon-musk/

viii PowerPoint presentation delivered April 2023 at North Dakota State University by Mark Hagerott, PhD, the Chancellor of the North Dakota University System. His research and writing are focused on the evolution of technology, education and changes in technical career paths.

ix Penrose, R. Shadows of the Mind. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996.

x Quoted in MacHale, D. Wisdom. London: Prion Books, 2002.

xi For me, duplication and imitation are distinct. Something is duplicated, such as having empathy for another’s painful experience, when it is the same physically and emotionally to the original. On the other hand, something is imitated if it appears to be externally the same, but is not internally identical. A computer can imitate empathy by mimicking humans’ external behavior, for example, but cannot duplicate the feeling required to be empathetic.

xii Delohery, C. “These three companies are making self-driving cars safer.” Utah Business, 25 October 2022. https://www.utahbusiness.com/are-self-driving-cars-safe-companies-in-car-safety/

xiii Casey, B.J., Getz, S. Galvan, A. “The adolescent brain.” Developmental Review 28 (2008): 62-77.

xiv Baumeiter, RF., Bratslavsky, e., Muraven, M., Tice, D.M. “Ego depletion: is the active self a limited resource?” J Pers Soc Psychol, 74(5) (1998): 1252-65.

Dennis R. Cooley, PhD, is Professor of Philosophy and Ethics and Director of the Northern Plains Ethics Institute at NDSU. His research areas include bioethics, environmental ethics, business ethics, and death and dying. Among his publications are five books, including Death’s Values and Obligations: A Pragmatic Framework in the International Library of Ethics, Law and New Medicine; and Technology, Transgenics, and a Practical Moral Code in the International Library of Ethics, Law and Technology series. Currently, Cooley serves as the editor of the International Library of Bioethics (Springer) and the Northern Plains Ethics Journal, which uniquely publishes scholar, community member and student writing, focusing on ethical and social issues affecting the Northern Plains and beyond.