In Ireland in the 1840s, a potato blight precipitated famine during which millions of Irish emigrated to the Americas or starved to death. Centuries earlier, the English took control of the Emerald Isle, and the official policy towards impoverished Irish peasants was, in the phraseology of Klaus Schwab, PhD, founder and executive chairman of the World Economic Forum: “You will own nothing, and we don’t care if you are happy.”

By the turn of the 19th century, the Irish population had increased far beyond what landowners needed to run their farms and plantations. The poor were increasingly regarded as a ‘useless class’ and financial burden. When the potato blight hit, there was plenty of food grown on Ireland’s ecstatically green fields, but it was exported to England.

What to do about the starving Irish masses? ‘You will be nothing’ was the elite’s verdict, and emaciated corpses of entire families littered roadways through lush pastures.

That was the Old Green Deal, and perhaps we are in for a technologically driven redo on a global scale. According to Yuval Noah Harari, author of Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow (2016), digital and other advanced technologies will soon produce a vast new useless class. At the same time, world leaders are aggressively pushing the New Green Deal, which threatens to impoverish, oppress and starve millions worldwide.

A true whangdepootenawah, defined as an Ojibwe word for “disaster” in the humorously satirical Devil’s Dictionary—but not in any online Ojibwe dictionaries. Perhaps a made-up word is most appropriate for a man-made catastrophe.

Demographic Winter Is Coming

At first glance, we still seem to be doing alright, despite current economic woes. There are ubiquitous worker shortages—not so useless, yet. But futurists tell a different, paradoxical story. On the one hand, impending demographic collapse would seem to make people more valuable to society. On the other hand, the automation/artificial intelligence (AI) revolution threatens to make most humans superfluous.

“Today the majority of the industrial nations are heading toward demographic death,” wrote David P. Goldman in It’s Not the End of the World; It’s Just the End of You: The Great Extinction of Nations, published in 2011. “For the first and only time in recorded history … prosperous, secure and peaceful societies facing no external threat have elected to pass out of existence.” (pg. 15)

Since then, the crisis has grown worse, as documented by Peter Zeihan in The End of the World is Just the Beginning: Mapping the Collapse of Globalization. Maintaining a country’s population requires a 2.1 total fertility rate, which the U.N. calculates “by summing age-specific birth rates over all reproductive ages,” typically 15 to 49 years old.

China, the most populous nation with 1.4 billion citizens, has one of the lowest rates at 1.3 and will see its population fall to half by midcentury, wrote Zeihan, an acclaimed geopolitical strategist. At the same time, China also has the fastest aging population in history. There will be many more retired workers, with experience and training—most of whom needing to be supported—than young people entering the workforce. What this means is that China’s days as a rising world power are numbered, Zeihan argued, which makes China quite dangerous in the near future.

The same demographic story repeats in the coming decades worldwide and dwarfs all other disruptions. “[C]ountries as varied as China, Russia, Japan, Germany, Italy, South Korea, Ukraine, Canada, Malaysia, Taiwan, Romania … will see their worker cadres pass into mass retirement in the 2020s. None have sufficient young people to regenerate their populations. All suffer from terminal demographics. The real question is how and how soon do their societies crack apart? And do they deflate in silence or lash out?” (pg. 60)

One of the major reasons Russia launched its invasion of the Ukraine this year, Zeihan contended, was because demographics will soon make it impossible to field a large enough force for foreign aggression while simultaneously defending its immense landmass.

Demographic disintegration will repeat in the 2030s and 2040s for nations including Brazil, Spain, Thailand, Poland, Australia and Switzerland. Then in the 2050s, countries including Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Mexico and Saudi Arabia will face the same fate unless they quickly deal with the crisis.

“The next batch of countries—mostly in the poorer parts of Latin America or sub-Saharan Africa or the Middle East—are even more concerning,” (pg. 61) Zeihan continued. Although their populations are far younger, their economies are extractive, importing food and other goods in exchange for exporting raw commodities.

In a globalized world, this model can’t make these countries wealthy but does enable survival. However, demographic collapse will precipitate deglobalization, producing massive famine and political upheavals while globalization’s jewels—“economic development, quality of life, longevity, health”—will fracture. (pg. 61)

The Weakness of Nations

Ironically, Zeihan cited rapid demographic expansion among globalization’s historical gems. Before World War II, various empires competed for raw materials and other resources, which led to armed conflicts. After WWII, the Cold War began and, to contain the Soviet Union, the U.S. instituted a global system of free trade. The U.S. Navy guaranteed security on the high seas, including oil exporting routes from the Middle East, such that any friendly nation could trade with any other friendly nation. This created globalism as we know it and enabled industrialization (or re-industrialization in Western Europe) and massive economic growth around the world.

Industrialization pushed most populations into urban centers as technology made agriculture more productive and less labor-intensive. At the same time, massive amounts of infrastructure and industrial plants needed to be built and then factories run. Jobs and higher standards of living attracted families but also diminished family size. In the countryside, there is room for children and they provide free labor. In the city, kids are very expensive projects. No surprise that birth rates dropped precipitously.

Paradoxically, populations increased dramatically under American-led globalization. The world has been at relative peace, limiting the number of soldiers and civilians killed in conflicts. Technological advances dramatically decreased infant mortality and increased life expectancy. The doubling of China’s population over the past 40 years was due mainly to increased life expectancy.

In addition, urbanization offered women paying work outside the home and engendered the women’s rights movement, which embraced contraception and abortion. As women filled secondary schools and then universities, the competition between career and family pushed fertility rates below sustainable levels.

The average fertility rate for the European Union is 1.5 and as low as 1.23 in Spain, while South Korea has the lowest at 1.08. Most countries cannot regain replacement birth rates perhaps ever, since economic, societal and military woes, which are interdependent, foretell geopolitical chaos furthering the weakness of nations.

Compound Disinterest

Given the dire nature of demographic collapse and years of forewarning, why have world leaders ignored the problem? Partly, it’s not as urgent for Americans. Our fertility rate has declined to 1.78, which gives us a generation to recover, if we start soon.

Even though American media is the least trusted on the planet, according to a recent Reuters Institute survey, it has the biggest megaphone along with social media. Positive stories about increasing family size run counter to the corporate mainstream media’s worldview. Nor do the unconceived have advocacy groups.

Also, America is stepping back from protecting global shipping lanes and functioning as the planetary police force. At the same time, regional powers are rising, including Russia, China, India, Turkey, accelerating deglobalization and our detachment from international affairs.

What will result geopolitically is unclear. While China is extending its military reach, Zeihan held that depopulation and deglobalization will cause the nation’s breakup. At the same time, China is racing to gain AI superiority, which would render a game-changing advantage. Yet zeroes and ones can neither be eaten nor converted into energy, and China is far from self-sufficient in these. Meanwhile, the U.S. is vying for AI supremacy and will have more people of working age than China by 2045. Does population matter?

Displacement & Death by Algorithm

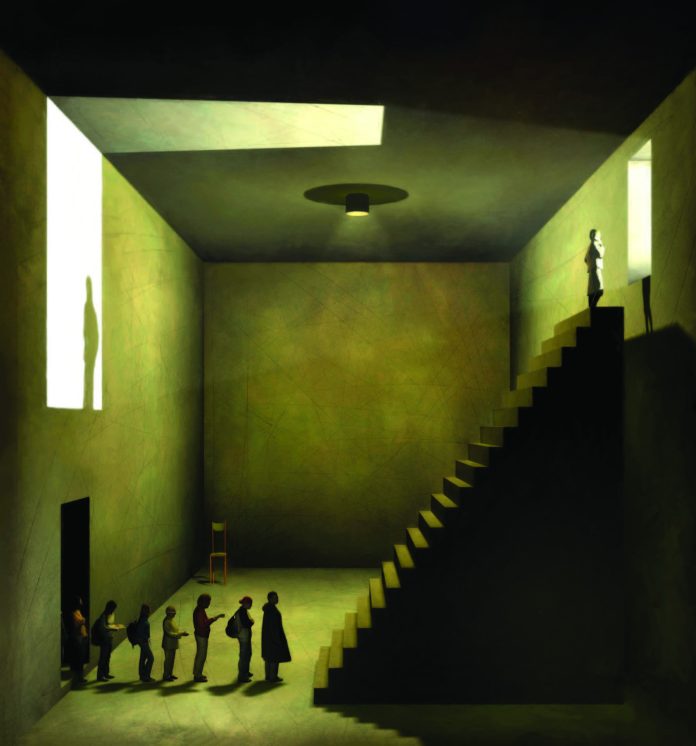

Today we also face a profound technological disruption that, according to Harari, could become devastating for most people. “As algorithms push humans out of the job market,” he wrote in Homo Deus, “wealth and power might become concentrated in the hands of the tiny elite that owns the all-powerful algorithms, creating unprecedented levels of social and political inequality.” (pg. 376)

Worse, this elite in the not-so-distant future will consist of upgraded humans who, due to biotechnical enhancement along with access to the most powerful AI, will “enjoy unheard-of abilities and unprecedented creativity, which will allow them to go on making many of the most important decisions in the world. … However, most humans will not be upgraded and will consequently become an inferior caste dominated by both computer algorithms and the new superhumans.” (pg. 403)

Would that Harari was a Hollywood scriptwriter, but he has a PhD in History from the University of Oxford and lectures at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. His books have sold more than 40 million copies in 65 languages. Recognized as a leading public intellectual, Harari often discusses global challenges with heads of state privately and publicly. In 2018 and 2020, he gave keynote speeches about humanity’s future in Davos, where the World Economic Forum annually convenes heads of state, CEOs of 1,000 major corporations and other leaders to decide our future.

Harari also wrote that from the elite’s perspective, populations will not only lose their economic utilitybut their military value too. Vast numbers of unmanned weapons systems (UAS) on land, sea, air and space will replace the massive armed forces of previous eras. Swarms of drones will be deployed more than waves of infantry, “along with small numbers of highly trained solders” and fewer “super-warriors.” (pg. 359)

Full robotic autonomy—where UAS would make kill decisions on the battlefield without human control—illustrates the descent of the status of man. This would be “death by algorithm” executed by a sophisticated toaster, as USAF Maj. Gen. (Ret.) Robert Latiff and I wrote in “With Drone Warfare, America Approaches the Robo-Rubicon” in The Wall Street Journal (March 2013).

The Great Decoupling

The underlying technological thrust Harari described as: “Intelligence is decoupling from consciousness.” (pg. 361) Until this high-tech moment, tasks requiring intelligence could only be accomplished with humans in charge. He gives examples—playing chess, diagnosing diseases, driving cars—that can now be completed via algorithmic machine learning. Going forward, more tasks and entire professions, including white collar, will be done better, faster and cheaper by computer systems, robots, 3D printing and so on.

Some futurists contend that this technological revolution will create more new occupations than it eliminates. Perhaps, if dynamic free-market capitalism continues to flourish. Even so, in Harari’s view, permanent job losses will occur as AI dominates tasks and professions involving cognitive skills.

Yet, some humans will maintain relevancy. Eric Schmidt, Google’s former CEO, in interviews after the publication of The Age of AI and Our Human Future (2021), which he cowrote with Henry Kissinger and Daniel Huttenlocher, foresaw the ubiquitous presence of AI assistants. While AI is far better than people at pattern recognition and processing data, it is also imprecise and inscrutable. AI can’t explain how it arrived at, for example, a disease treatment protocol. Experienced physicians will still be crucial in healthcare, albeit fewer in number.

What is both magnificent and terrifying about AI is its ability to learn and, with increasing computing power, to learn ever more rapidly and intelligently. AI is already being used to compose symphonies and produce paintings. “To make sense of our place in the world,” wrote the authors of The Age of AI and Our Human Future, “our emphasis may need to shift from the centrality of human reason to the centrality of human dignity and autonomy.” (pg. 194)

‘What is a human being worth?’ is the overwhelming question of this century.

Here’s a famous poem by Basho, a 17th-century Japanese haiku master: The pond is so old, a frog jumps into the sound of water. If intelligent machines solve urgent complex problems, we cheer. But if an AI program spits out breathtaking verse—or any artistic masterpiece—are we not diving into a mockery of the human soul? We earn wisdom in the painful, irreplaceable struggle to become (the original meaning of the verb “worth”). Become what? A human, who is ever the questioning, the questioner and the question, which is our endlessly reverberating response to Being, whatever that is. No, AI, don’t tell us.

Cyber River, Geopolitical Oceans

“[A]ll people in the world are living alongside the same cyber river, and no single nation can regulate this river by itself,” Harari said in a TEDx talk in 2017. “All the major problems of the world today are global in essence, and they cannot be solved unless through some kind of global cooperation.”

Harari argued that nationalism lacks the scale and scope to resolve these problems. Yes, greater international cooperation is required regarding the myriad of emerging technologies. But as we saw during the recent pandemic, governments throughout the West simultaneously implemented exactly the same repressive and immensely damaging measures (which digital tools enabled but didn’t cause). This was less cooperation than lockstep globalism inspired, if not directed, by the World Economic Forum, which trains many world leaders.

The pandemic response was the first stage in realizing the World Economic Forum’s vision of the “Great Reset.” The vastly more transformative stage, underway already, is the full-scale implementation of iterations of the New Green Deal. The main measures include a forced transition from fossil to green energy sources; blocking fossil fuel development even in poor countries, condemning them to misery; and restricting agricultural production—just as the U.N. warns of multiple famines this year and more in 2023.

Will versions of the New Green Deal produce a whangdepootenawah for “useless” humans? Such questions will be discussed in the spring issue of Dakota Digital Review—just as the folly of green energy policies, in eschewing the primacy of abundant food and cheap, reliable fuel, will become blazingly apparent in Europe and elsewhere. Also, to be examined is the underlying rationale that great sacrifices are required to fend off climate change’s existential threats, which human activity is allegedly causing. Are climate-emergency claims valid, or do they function as cover for the real objective: a highly technocratic, totalitarian ruling class? Perhaps demographic collapse is seen as an opportunity.

The Great Reset also entails greatly strengthening, via AI, digital methods to censor dissent throughout social media and the internet. “We should … fear AI because it will probably always obey its human masters, never rebel,” Harari warned in “Why Technology Favors Tyranny” in Atlantic Monthly (October 2018). “[AI] will almost certainly allow the already powerful to consolidate their power further” potentially creating “a digital dictatorship” in which most “humans risk becoming similar to domesticated animals.”

Yet, “[t]oday, a new epoch beckons,” the authors of The Age of AI and Our Human Future concluded. “Individuals and societies that enlist AI as a partner to amplify skills or pursue ideas may be capable of feats—scientific, medical, military, political and social—that eclipse those of preceding periods.” (pg. 205) Solar or lunar?

In Horace, the Roman poet, a rural peasant leaves his village and for the first time encounters a river. He sits down to wait patiently for it to flow by. Two millennia later, that river—now cyber— still flows into churning geopolitical oceans driven by deep technological currents.

Patrick J. McCloskey is the Director of the Social and Ethical Implications of Cyber Sciences at the North Dakota University System and serves as the editor-in-chief of Dakota Digital Review. Previously, he served as the Director of Research and Publications at the University of Mary and editor-in-chief of 360 Review Magazine. He earned an MS in Journalism at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism. McCloskey has written for many publications, including the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, National Post and City Journal. His books include Open Secrets of Success: The Gary Tharaldson Story; Frank’s Extra Mile: A Gentleman’s Story; and The Street Stops Here: A Year at a Catholic High School in Harlem, published by the University of California Press.