Disease & Technological Transformation

At 7 p.m. on November 9, 1872, a fire started in the basement of a warehouse at the corner of Kingston and Summer Streets in Boston, Massachusetts. Two hours later, the fire was consuming a three-block radius. All 21 of the city’s fire engine companies responded. Even so, the fire advanced south quickly to the waterfront, incinerating docked vessels and wharves. By 6 a.m., the fire was roaring through the center of downtown and wasn’t contained until midday. In total, the fire destroyed 766 buildings, leaving a large swath of the city in smoldering ruins.

A major reason the fire became so disastrous began in late September. In pastures around Toronto, Ontario, horses and mules started showing signs of a respiratory illness. By early October, this equine influenza spread across the southern border. Within a few weeks, influenza infected horses in Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore and then out to Chicago and south to cities as far as Jacksonville, Florida. Big cities contained large populations of horses in dense clusters, facilitating the spread of a new illness for which the animals had no immunity.

The influenza moved much faster than galloping horses—that is the flesh and blood kind. Ironically, the “iron horse” provided the means. Horses were shipped regularly between cities, facilitating infection. Mapping the disease showed that it followed rail lines strictly, reaching San Francisco by spring but completely absent from areas unconnected by rail.[1]Kheraj, Sean, “The Great Epizootic of 1872-73: Networks of Animal Disease in North American Urban Environments,” Environmental History, Oxford academic (oup.com), April 24, 2018.

The “most explosive equine panzootic ever documented”[2]Morens, David M. and Taubenberger, Jeffery K., “Historical Thoughts on Influenza Viral Ecosystems, or Behold a Pale Horse, Dead Dogs, Failing Fowl, and Sick Swine,” in Influenza and Other … Continue reading ranged from British Columbia to Central America. Toronto was described as a “vast hospital for diseased horses,”[3]Census of Canada, 1870–71, Vol. 3 (Ottawa: 1875), 106–7; “Horse Epidemic,” Globe, October 5, 1872, 1; “Horse Epidemic,” The Mail, October 7, 1872, 4; William Henry Irwin, ed., Toronto … Continue reading and the same scenario repeated throughout the continent.

Like COVID-19, the equine influenza was highly contagious. At least three-quarters of the horses nationwide contracted the disease. Also, like COVID, the influenza’s mortality rate was low at 3.7 percent in New York City[4]Norris, David A., “When a Plague Tormented America’s Horses,” October 2019. and would have been considerably lower but many horses in urban centers were kept in unsanitary conditions.[5]Smith, Tara, “The 1872 Equine Influenza Epidemic that Sickened Most U.S. Horses,” July 1, 2015.

Standstill

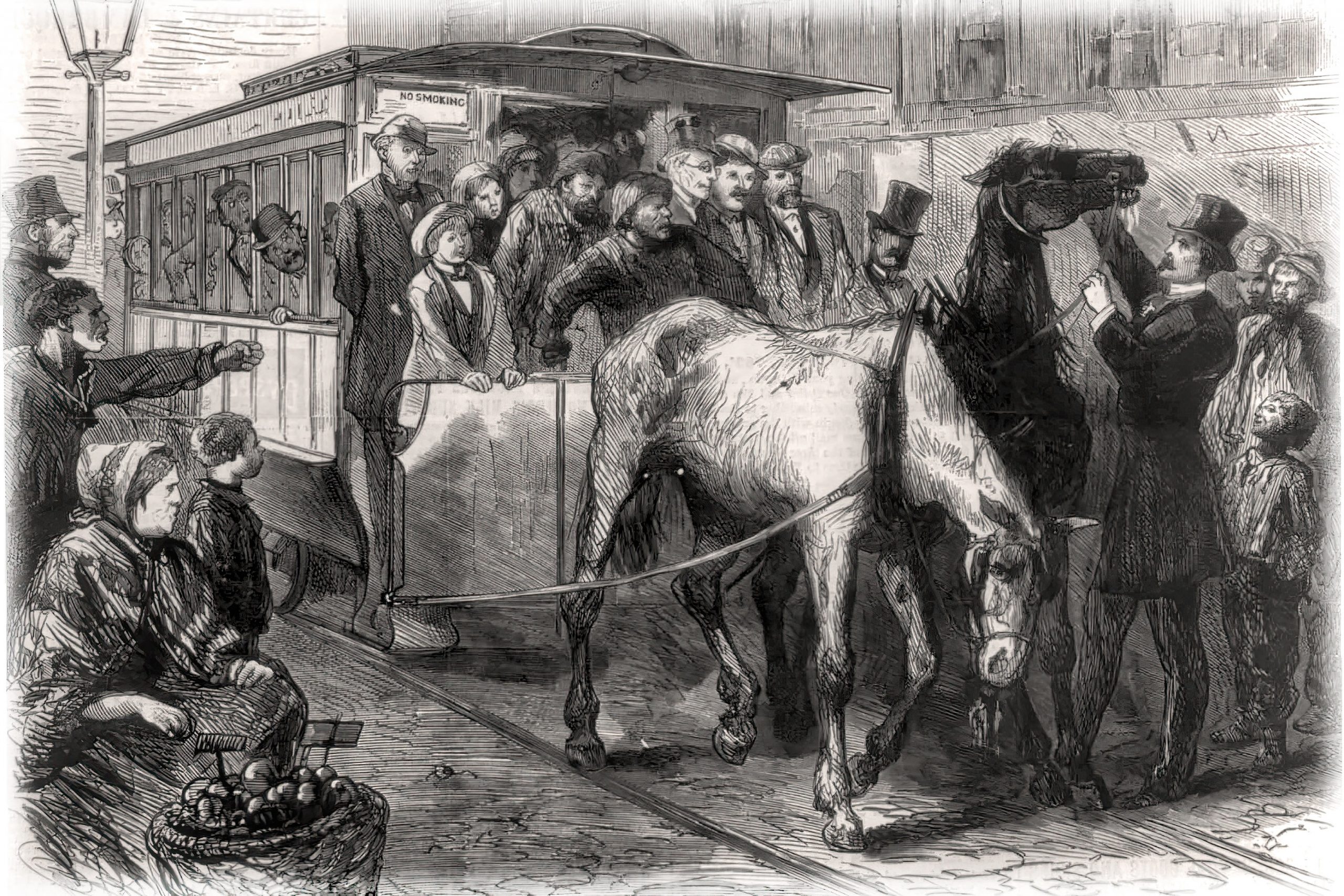

As if in lockdown, life in cities and towns across the country stood still. Horses were central to commerce and transportation. Where streets once thronged with horse-drawn carts, carriages and trolleys, empty avenues presaged 2020. It was difficult to impossible to supply food and other necessities. As winter approached, families in the North feared a coal famine, since horses weren’t available to bring the coal out of the mines, let alone deliver it to residents. The economy slid quickly into recession.

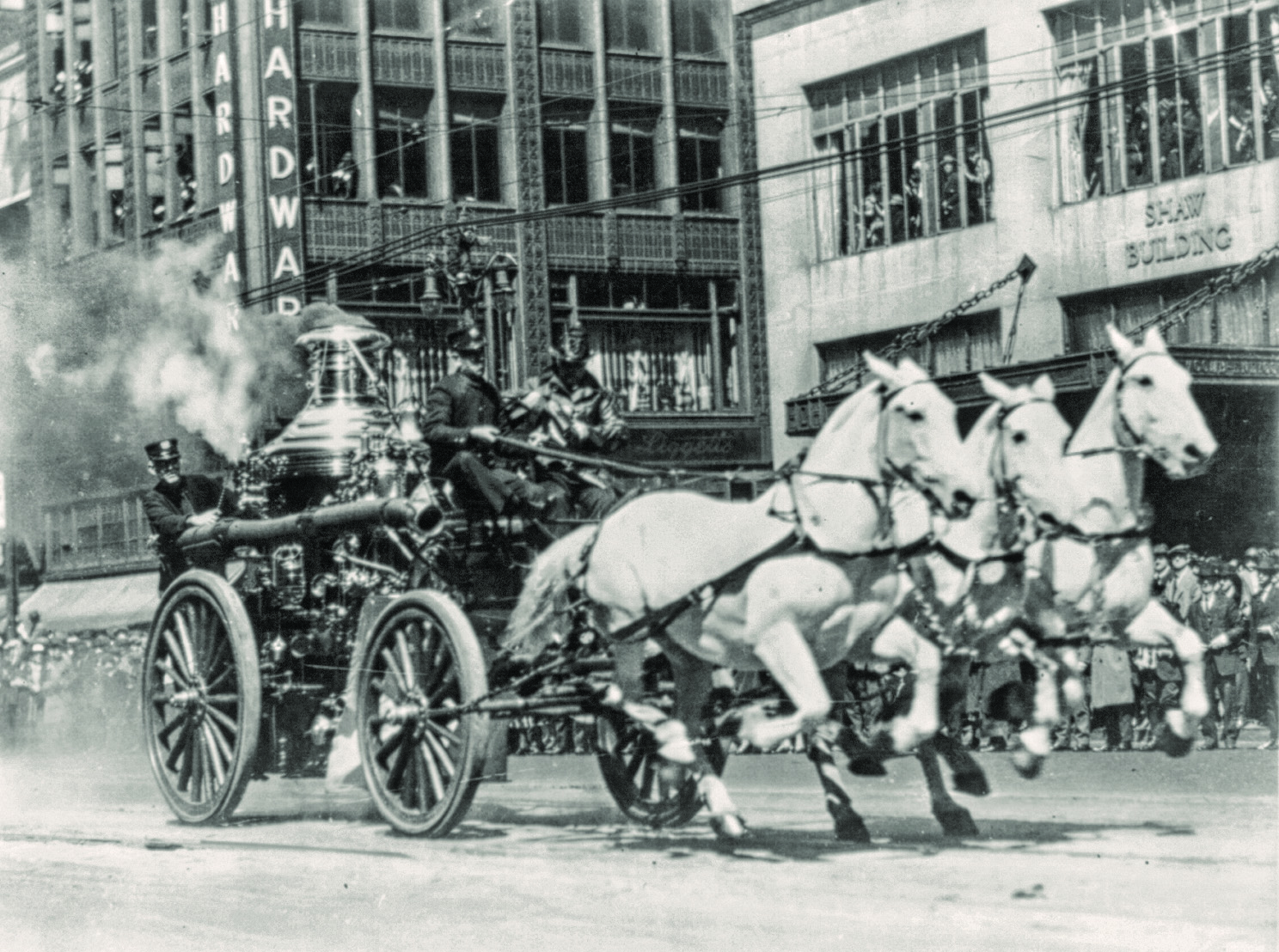

A contributing factor in the Boston inferno, as in the Great Chicago Fire a year earlier, was the fact that most buildings were made of wood, as well as streets and sidewalks. The Chicago fire, however, was driven by strong winds making any effort by fire companies useless. In Boston, a significant factor was what wasn’t moving: horses and therefore many of the heavy pump wagons that were urgently needed to corral the fire.

Iron & Electric Horses

The influenza epidemic highlighted how crucial horses were to the economy and almost all human activities. Horses were cherished by many people and a new appreciation of their worth was acknowledged. However, their long-term fate was also sealed.

Newspapers sought some levity with jokes, for example, that iron horses are immune to the disease. Looking forward, that turned out to be more witness than wit. In 1873, just after the equine influenza put the city’s beasts of burden out of commission, San Francisco initiated cable car service. There were electric trolley cars by the 1880s, and by 1902, 97 percent of the nation’s streetcar systems were powered by electricity.[6]Ibid, Norris. Urban life would never again be so disrupted by horse plague. In New York City, three separate elevated train lines were built from 1873 to 1878.[7]“Nevius, James, The Elevated Era,” June 27, 2018.

Horses were still beloved and useful, especially on farms. According to the 1870 U.S. census, there were 38.6 million people and 7.15 million horses. The number of horses increased for the rest of the century to 21.5 million in 1900,[8]Kilby, Emily R., “The Demographics of the U.S. Equine Population,” Chapter 10 in The State of Animals IV: 2007, Humane Society Press, Washington, D.C. and the proportion also grew from one horse for every 5.4 people to one per 3.5 people. The horse population peaked in 1915 at 26,493,000 as large numbers were being shipped overseas to serve in World War I, more than a million horses and mules by war’s end.

In 1915, the ratio slightly increased to one horse for every 3.8 humans. At the same, however, automobiles were starting to be produced in large numbers. As with all products in a market-based economy, cars and trucks improved in quality and decreased in price such that small businesses and ordinary citizens could begin to afford them. As mass production of gasoline-powered tractors began in the 1920s, the need for horses on the farm decreased rapidly. From 1915 to 1960, the American population increased from 100.55 million to 180.7 million, at the same time as the number of horses fell by 88 percent from 26.5 million to 3.1 million (one horse for every 58 humans).

Tractor production peaked in 1951 at 564,000 units.[9]White, William J., “Economic History of Tractors in the United States,” Economic History Association. Automobile production increased from 806,989 in 1915 to 6.1 million in 1960.[10]U.S. Automobile Production Figures, Wikipedia. Technological transformation took decades from the 19th into the 20th centuries, unlike the compressed time change takes today. Unforgotten was how vulnerable a society reliant on biological units is, and that disease can devastate the economy.

Hobby Horses

Our equine fellows no longer work for a living, other than as race, rodeo or show horses. None of these activities are essential to the economy. Most have slipped into the realm of their owners’ pastimes to become hobby horses of a sort. Happily, their numbers have increased to 7.25 million today,[11]American Horse Council, U.S. Horse Population—Statistics. a testament to the bond between horse and man.

What about people and our bonds?

Unlike the epizootic, COVID shutdowns were not the result of a pandemic putting so many people in hospitals and the morgue that the economy could no longer function. Rather, it was fear. Given the acceleration of the digital transformation, discussed in this issue’s first article, human vulnerability is quickly being reduced.

Much has been written, broadcast and podcast about AI and automation replacing vast numbers of jobs in all sectors. Will the new economy provide even more jobs than those lost, as argued in “Robophia: Work in the Age of Robots,” in this issue?

Or will a massive “useless class” be created? If so, a remedy favored in Silicon Valley is the universal basic income.[12]Sadowski, Jathan, “Why Silicon Valley is Embracing Universal Basic Income,” The Guardian, June 22, 2016. Does this deliver us to a glorious post-work future or techno-socialist misery? Are people without work set free to realize their creative dreams or rendered without even the purpose of a hobby horse? And what will creativity mean if free expression is limited by the Big Tech censorship that became so blatant in 2020?

Will we overcome these challenges and integrate the human and the technological to everyone’s benefit? Or are we heading for a social conflagration?

Despite the smoke, at least many of the questions are clear.

Patrick J. McCloskey is the Director of the Social and Ethical Implications of Cyber Sciences at the North Dakota University System and serves as the editor-in-chief of Dakota Digital Review. Previously, he served as the Director of Research and Publications at the University of Mary and editor-in-chief of 360 Review Magazine. He earned an MS in Journalism at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism. McCloskey has written for many publications, including the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, National Post and City Journal. His books include Open Secrets of Success: The Gary Tharaldson Story; Frank’s Extra Mile: A Gentleman’s Story; and The Street Stops Here: A Year at a Catholic High School in Harlem, published by the University of California Press.

References

| ↑1 | Kheraj, Sean, “The Great Epizootic of 1872-73: Networks of Animal Disease in North American Urban Environments,” Environmental History, Oxford academic (oup.com), April 24, 2018. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Morens, David M. and Taubenberger, Jeffery K., “Historical Thoughts on Influenza Viral Ecosystems, or Behold a Pale Horse, Dead Dogs, Failing Fowl, and Sick Swine,” in Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses 4, no. 6 (2010): 331. |

| ↑3 | Census of Canada, 1870–71, Vol. 3 (Ottawa: 1875), 106–7; “Horse Epidemic,” Globe, October 5, 1872, 1; “Horse Epidemic,” The Mail, October 7, 1872, 4; William Henry Irwin, ed., Toronto City Directory for 1872–73 (Toronto: Telegraph Printing, 1872), 321; “Epidemic Among Horses,” Leader, October 9, 1872, 2; “Horse Disease,” Perth Courier, October 11, 1872, 2. |

| ↑4 | Norris, David A., “When a Plague Tormented America’s Horses,” October 2019. |

| ↑5 | Smith, Tara, “The 1872 Equine Influenza Epidemic that Sickened Most U.S. Horses,” July 1, 2015. |

| ↑6 | Ibid, Norris. |

| ↑7 | “Nevius, James, The Elevated Era,” June 27, 2018. |

| ↑8 | Kilby, Emily R., “The Demographics of the U.S. Equine Population,” Chapter 10 in The State of Animals IV: 2007, Humane Society Press, Washington, D.C. |

| ↑9 | White, William J., “Economic History of Tractors in the United States,” Economic History Association. |

| ↑10 | U.S. Automobile Production Figures, Wikipedia. |

| ↑11 | American Horse Council, U.S. Horse Population—Statistics. |

| ↑12 | Sadowski, Jathan, “Why Silicon Valley is Embracing Universal Basic Income,” The Guardian, June 22, 2016. |