One day last year, my sister approached me to ask a journalistic favor. Carol owns a chocolate shop in Somerville, New Jersey, a county seat about 40 miles west of New York City, and the place where I began my reporting career in 1975. The borough’s government, Carol told me, was going to quadruple the charge for on-street parking from 25 cents to one dollar an hour and cut back on the free evenings and holidays. Worse yet, the price hike was supposed to take effect at the start of the Christmas shopping season. Along with a group of other downtown merchants, Carol was furious, because their big competitors in a mall several miles away had acres of free parking to entice customers. So the local shopkeepers were hoping to take their complaints public, partly by getting it into the newspaper. My sister wanted to know if I had any advice.

That simple question set off a disturbing realization for me, as a journalist, an educator and a citizen. Decades ago, when I was a summer intern and then a full-time reporter on the local paper, the Courier-News, a mainstay of our mission was to cover precisely the sort of parochial controversy my sister described. We had a staff of about 60 reporters, editors and photographers based in a handsome and highly visible building just outside Somerville, and the baseline of all our coverage was sending staff members to attend the myriad meetings of local government.

I can’t say that such duty was scintillating—few things can be as soul-deadening as sitting in on a four-hour-long meeting of the town council or the board of education—but most of us on the Courier-News recognized the importance of holding the public sector accountable in our humble, even humdrum way. The process ran in the reverse, too. We journalists were not some distant, superior caste to the people we covered. We lived and worked and ate and drank among them. Our salaries put us in the low end of the middle class.

While many of my peers on the younger side of the newsroom had attended college and become imbued with the idea that journalism was both a profession and an academic discipline, the older generation was especially rooted to the communities around us, where they had resided for decades. There was the wife of a longtime police officer, a veteran of World War II bombing missions, a refugee from the Hungarian revolution whose American life had started at a displaced-persons camp in Central New Jersey. At the next newspaper where I worked, in the suburbs of Chicago, a number of our reporters were working mothers in their 30s or 40s who had mortgages to pay and kids to help with homework.

If a nation expects to be ignorant and free, in a state of civilization, it expects what never was and never will be.

– Thomas Jefferson

By the time my sister came to me with her request, the Courier-News was a shell of its former self. The building had been sold and razed. The staff had been cut by something like two-thirds. Instead of vigorously competing against the daily papers in nearby suburbs like New Brunswick and Woodbridge, the Courier-News had been put under joint ownership with them, sharing a common web portal.

I found myself telling Carol, “I don’t know who can hear you.”

I made that depressing and impromptu admission just a few weeks before Donald Trump was elected president, in part thanks to his attacks on the news media. And over time, I have come to believe the admission and the election have more than a coincidental relationship. The ability of this president to brand critical, accurate reporting as “fake news” and to campaign against journalists, sometimes inciting his rallies against specific ones like Katy Tur of MSNBC, derives from more than class resentments. Those resentments thrive when people in large sections of the country have less and less of the chance to know a working journalist as a neighbor, a fellow churchgoer, a companion in the PTA.

Admittedly, journalists have sometimes given fodder to the Trumpian attacks. CNN, for example, erroneously reported that Anthony Scaramucci, briefly a White House aide, had been in stealthy contact with Russian operatives. While on the staff at Politico, Julia Ioffe tweeted out an offensive insinuation of incest between the president and his daughter Ivanka. But the news organizations did punish Ioffe and the CNN correspondents, costing the latter their jobs. The extravagant calumnies that Trump lobs against even responsible journalism go uncorrected in his part of the political world.

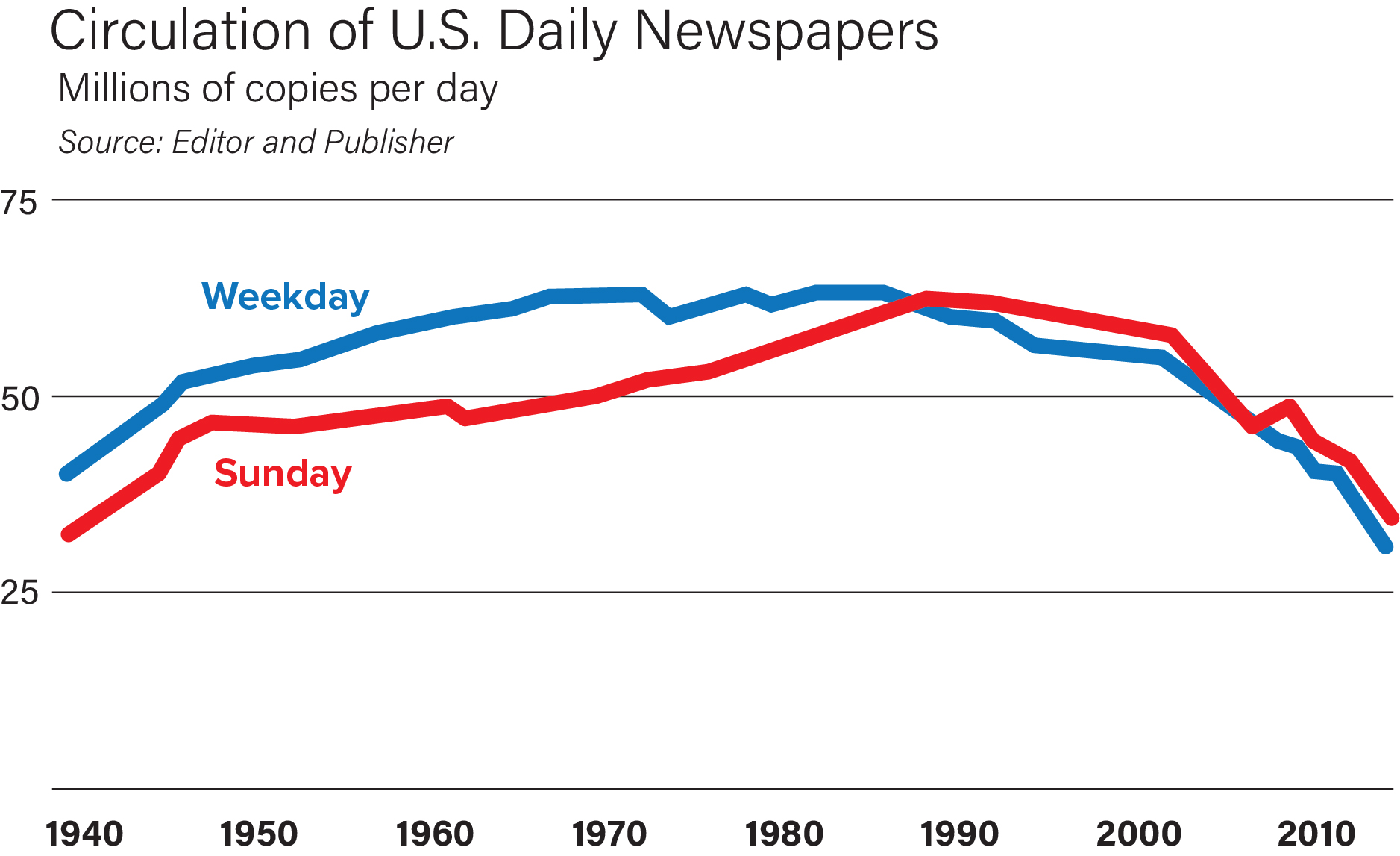

What I have seen in suburban New Jersey is even more extreme the deeper inland you get from the coasts. The common narrative of the news industry being in financial trouble and shedding jobs is only partially true. As a study by the website Politico showed, jobs in newspapers indeed fell by more than half from 365,000 in 2006 to 174,000 in 2017. Yet during the same period, jobs in online publishing and broadcasting soared from 69,000 to 207,000.

So the overall drop in journalism jobs was not nearly as catastrophic as it first appears. The problem, though, is that the job picture is wildly asymmetrical. Those jobs in online journalism arose overwhelmingly in Los Angeles, San Francisco, Seattle, Chicago and the Washington-to-Boston corridor. Put another way, the share of reporting jobs based in just three major cities—Los Angeles, New York and Washington—went from 1 in 12 in 2004 to 1 in 5 in 2014, according to data from the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics.

One result of this hollowing-out process is the concept of “news deserts,” meaning places that have few or no local newspapers. A study of the phenomenon by the University of North Carolina has kept a running tab of newspapers that have been shut down or merged since 2004—a total of 56 thus far, in heartland places like Slidell, Louisiana, Derby, Kansas, and Tarboro, North Carolina. More importantly, the study contends that even where newspapers still operate in small and mid-sized markets, the changing nature of ownership had led to a decrease in the kind of corporate citizenship that felt it important to keep such papers thoroughly staffed and realistically budgeted as a public service. The new wave of newspaper owners are hedge funds, pension funds and similarly passive investors, rather than the families (Sulzberger, Chandler, Bingham) or corporations (Knight-Ridder, Gannett, Scripps-Howard) that dominated in the past. The new “media barons,” as the report dubs them, are demanding profit margins that can only be sustained by rounds of budget cuts, mostly meaning layoffs of staff and reductions in coverage.

In human terms, the combination of shutdowns, mergers and staff cuts, many of them ordered by geographically distant owners, means that the reporter, editor, photographer or layout designer isn’t a fixture of community life any more outside the coastal boom cities of online journalism. The aspiring young journalists in a Nebraska or an Arkansas, or for that matter a Central New Jersey, have far less likelihood than I did of being able to make a career in their own regions. Economic gravity now will move them toward the Atlantic and Pacific, or lure them out of journalism entirely into the fastgrowing, better-paying field of public relations.

Stereotypes, as we know, flourish when there is not much human evidence to contradict the caricature. If you don’t live around journalists, if you don’t bump into them at the hardware store or the diner or the Little League game, then you’re so much more susceptible to buying into the cartoon image of a haughty, superior, obsequious, condescending city slicker. If you’ve never seen how the reporter on the local paper decently covered your town’s government, if you’ve never been responsibly interviewed by such a reporter about your art exhibit or prize livestock or drum-and-bugle corps, then you’re so much more susceptible to the corrosive idea that critical news, especially of the investigative variety, must be fake news.

When I ran my thesis by an acquaintance who edits a newspaper in southern Ohio that endorsed Donald Trump for president, he pushed back slightly. He told me that his readers still appreciate the local reporters and editors and save their venom for the big-city, coastal, “elite” media. I was not entirely persuaded. Rather, I was reminded of polling that shows that even people who despise Congress as an institution give decent marks to their own representatives there. The exception becomes just one more way of proving the rule.

As for my sister and her chocolate store, the Somerville merchants were able to raise enough of a clamor on their own that the borough rolled back dollar-an-hour parking to 50 cents. The only problem, Carol tells me, is that hardly any customers know, because the compromise was never reported in the local paper.

Postscript: Several months after I wrote this essay, the Courier-News happened to write a feature story about my sister’s shop. I was delighted for her to get the publicity. But nothing in this serendipitous event has changed my overall sense of the perilous state of my former newspaper and so many others like it.

Free speech, exercised both individually and through a free press, is a necessity in any country where the people are themselves free.

– Theodore Roosevelt

Here is a partial list of the newsroom layoffs, furloughs and closures caused by the coronavirus [The Poynter Institute, December 8, 2020]:

- The Poynter Institute, December 8, 2020.

- Lee Enterprises had furloughs and cost-cutting measures, including a 20% pay cut for executives.

- The Capital Times in Madison, WI, announced furloughs and pay cuts.

- Forum News Service reported layoffs and the end of Monday and Friday print in its “more than two-dozen newspapers in Minnesota, North Dakota, South Dakota and Wisconsin.”

- The Forum (Fargo, North Dakota and Moorehead, Minnesota) will cut to two print days a week and use the mail to deliver the newspaper, eliminating carrier jobs and most circulation. It is owned by Forum Communications.

- McClatchy furloughed 4.4% of staff at its 30 papers around the country.

- Tribune Publishing announced permanent pay cuts of between 2% and 10% and executives will take pay cuts. Tribune newsrooms include the Chicago Tribune, New York Daily News, The Baltimore Sun and The Virginian-Pilot. It also had furloughs.

- The Los Angeles Times had furloughs and pay cuts. The LA Times parent company California Times closed three community newspapers and laid off 14 staff members.

- ESPN is laying off 300 people and leaving 200 positions unfilled.

- Sound Publishing in Washington state laid off 70 people in its Washington and Alaska newsrooms. Sound Publishing owns 49 newsrooms, and the layoffs make up 20% of its workforce. Sound also suspended four print publications in Kitsap County and reduced staff.

- The Salt Lake Tribune and Deseret News will both switch from seven days of print to one. The two Utah papers end their joint operating agreement, resulting in the closure of the print facility that serves both and the end of 161 jobs and another 18 layoffs, including six journalists, from the Deseret News.

- The Kansas City Star is leaving its downtown offices and printing plant, resulting in 124 job cuts.

- Fox News will lay off 3% of staff. Employees in hair and makeup were the most impacted.

- NBCUniversal is cutting executive pay by 20%.

- CBS announced several rounds of layoffs – first 50 from CBS News, then an additional 400 at ViacomCBS.

- KFGO in Fargo, ND, has cut two positions. It is owned by Midwest Communications, Inc.

- The Great Falls Tribune in Montana shut down its printing press, ending 21 jobs. It will print in Helena.

- The Minneapolis Star Tribune has had four days of furloughs in both quarter two and quarter three for newsroom and non-newsroom employees, excluding production plant employees and fleet drivers.

This list grows every day.

Samuel G. Freedman is the author of seven books, a former columnist on religion and education for The New York Times, and a tenured Professor of Journalism at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism. Freedman was named the nation’s outstanding journalism educator in 1997 by the Society of Professional Journalists. Freedman’s most recent book, Breaking the Line: The Season in Black College Football That Transformed the Sport and Changed the Course of Civil Rights, was published in 2013 to remarkable critical acclaim. Freedman’s first book, Small Victories: The Real World of a Teacher, Her Students, and Their High School, was a National Book Award finalist, and The Inheritance: How Three Families and the American Political Majority Moved from Left to Right was a Pulitzer Prize finalist.