Our society depends on complex systems for energy, transportation, sustenance, medical care, emergency response and security. Natural disasters and cyber and terrorist attacks have demonstrated the brittleness of our infrastructure, which is based in computerized control systems. Without resilience, this leads to complex system failure. While these control systems have provided cost savings through automation, which enables fewer people to control increasingly larger systems, many of these systems have been built methodically with reliability in mind, but not resilience.

“Resilience” is the capacity of a control system to maintain state awareness and to proactively maintain a safe level of operational normalcy in response to anomalies, including malicious and unexpected threats.[i]

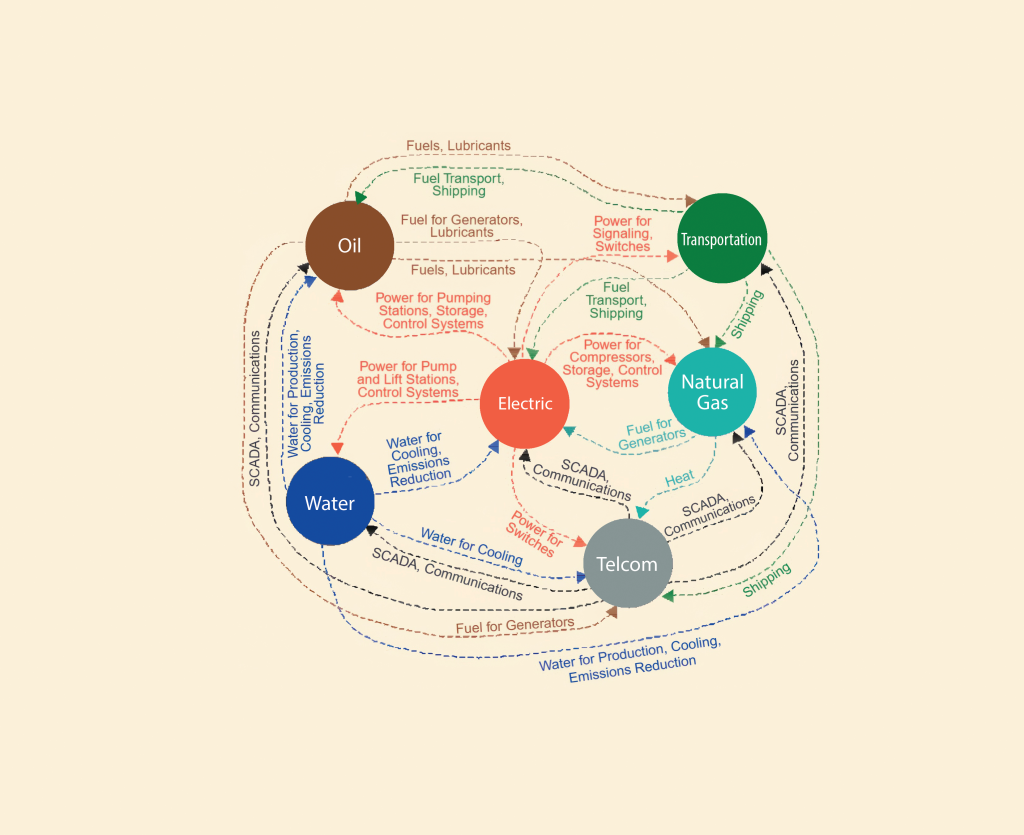

Control systems are comprised of interconnected devices, software modules and communications links, which collectively exhibit emergent properties or behaviors beyond those of individual elements, as shown in the illustration[ii] below. Complexity in a system arises when element dependencies and interdependencies supersede the importance of individual elements. When individual elements fail or are intentionally compromised, unforeseen and undesirable behaviors can propagate to create a broader impact to the infrastructure system. The susceptibility to this behavior can be termed system rigidity or brittleness of the control system. One of many examples includes the August 2003 power blackout in eight northeastern states and southeastern Canada.[iii]

In this case, a daisy chain of events included control-system and human-interpretation issues. The problem is characterizing and resolving the interactions with individual elements in such a way that the recognition of failure is localized and addressed to ensure the root cause is not a common source of failure.[iv]

There are generally two ways that resilient systems address threats that include failure and attack: adaption and/or transformation. Adaptive systems include components designed to function broadly in multiple roles or states, allowing self-modification and emergent properties that counterbalance anomalies while preserving mission-critical function. Transformable systems have the ability to reconstitute into fundamentally new systems when external forces render an existing system untenable.

Ideally, both adaption and transformability are integrated to yield the polymorphic nature of resilient control systems.

Architecting for the Threats

In considering the ever-increasing complexity of our critical infrastructure and the underlying control-system architectures, a concern of those researching resilience is how to “restructure” this complexity to prevent cascading failures from a variety of threats. These threats comprise both unexpected failures from many causes, including malicious outsiders and insiders and benign, unintended error. While these diverse sources seemly require different approaches, a decomposition principle is already implied by the evolution of current control-system designs.

The distributed control elements of control systems are associated with some optimally stabilizable entity. This can be seen from looking at chemical process plants, where a collection of separate unit operations makes up an integral plant.[i]

The unit operation, in this case, defines an area of local optimization. Within the operation, many physical variables may exist. In a plant made up of many unit operations, the process of determining how to optimally stabilizable entities normally results in a minimization of the interactions between individual operations. That is, normally only a few physical variables will make up the interactions between unit operations. For example, the flow between unit operations must remain within a specified range, as the downstream operation is designed to be stabilized for operation within that range.

The process of determining unit operations suggests a less complex approach for subdividing infrastructure to increase resilience, including how the power grid might be subdivided into various forms of microgrids. These microgrids include localized generation and control to feed nearby consumers as compared to macrogrids, where bulk generators provide power to consumers through regional transmission systems and wide-area controls. Within these subdivided areas, power stability is maintained against cyber-physical threats and localizes the ability to regulate the effects of destabilizing forces, such as intermittent generation.[ii] Through minimization of cyber, control, power and other dependencies and interdependencies, local regions maintain their stability and prevent cascading effects.

Where interdependencies and dependencies remain, polymorphic isolation techniques can be concentrated to counter propagation of threats. The result is a foundation or building block for greater efficiencies, where wide-area supervisory strategies can be built without engendering complex failures.

Resilience Starts with Interdisciplinary Education & Teams

A basis for current architectural considerations to achieve resilience has been advanced, but what does the future hold to optimize these systems against threats, and how will science and engineering advance within the educational community? That is, what should a student be exposed to before graduation? If you go through an engineering track, you are exposed to curricula that have evolved slowly over recent decades. These curricula include aspects that are unrelated to the discipline, historically integrated to provide a broader “education,” as compared to vocational training. This Renaissance-man perspective, in contrast, goes back centuries. While I would like to question why current humanities students aren’t required to take a technologies class to broaden their education, I will instead use this same context as a segue to future workforce needs.

The Renaissance-man perspective suggests that a liberal education is beneficial in developing critical thinking beyond a single subject area. Whether this is being achieved in the university environment today is worthy of discussion on its own, but I will suggest that to solve today’s complex problems, education that exposes students to the complexity of issues is critically important. Challenges in cybersecurity, control-system autonomy and human interaction with autonomy cut across a range of disciplines from sciences and engineering to the liberal arts. Recognizing and establishing interdisciplinary education will provide the fundamental educational insights required to address these challenges for Science, Technology, Engineering, Math (STEM) students into the future.

From a practitioner standpoint, engineers often work with technicians, but did their education provide a perspective on each other’s value and contribution to a team? This is unlikely. Yet the dynamic established by multidisciplinary engineering teamswould benefit from the perspective provided ahead of entering the job market.

Establishing university capstone projects as an interdisciplinary exercise can address this, including partnering between engineering and technician schools. For example, having technicians on the team take design input from the engineers and, using this information, successfully build a bench scale pilot per specification. The resulting dynamic between the engineers and technicians creates a positive understanding of the professional dynamic you would see in the workplace, including the contributions of separate disciplines and trades.

Many of us have worked on projects with different disciplines, but did they effectively communicate? Was there a clear appreciation of the importance of each other’s contribution?Establishing this dynamic is even more important with teams that cross not only engineering boundaries, but the boundaries between science and engineering and the underlying disciplines.

Today’s highly technological environment has created some natural challenges for the next generation of bright young minds. The desire to advance to a “Star Wars” or “I Robot” level of control system autonomy is upon us, fulfilling an ongoing desire to reduce the cost of production and efficiency. However, a focus strictly on the autonomy without recognizing the degrading effects of the threats to this autonomy leads to systems with catastrophic failures, so the pathway to achieve resilience while developing these systems is critical to their success. Success is not only defined as an assurance that these new control systems will be threat-resilient (from cyber-attack, hurricanes, human error, control system failure, etc.), but that the infrastructures they control are threat resilient, where failures are quickly recognized and mitigated. As the threat recognition and mitigations are complex, resilient solutions are not owned by any one person or discipline, but in combination.

Effectively providing teams that will successfully address this resilience challenge is both an educational challenge and a mindset change in team building.

Advancing the Science & Engineering of Resilient Control of Power Systems

To advance interdisciplinary education, I coauthored and coedited a college-level book that we developed based upon the syllabus for a special topics course, which was prototyped by several universities. The book seeks to establish a perspective for college students on automation’s unique challenges for our society, with a focus on a common element we all depend on: the power grid. Perspectives are provided on a simulation of this real-life system, providing a backdrop on how a power control system works and how it can fail. Similar to the multidisciplinary team,the outline of the book includes an account of how the various disciplines of the book’s contributors advance the science and engineering of resilience.

Over the last decade, research universities in Idaho, Minnesota, Nevada, Washington and elsewhere have held a one-semester special topics course that included both graduate and undergraduate teams. A simplified background in control systems, cybersecurity, human systems, power systems, etc., are provided during the course for familiarity, tailored to students from multiple disciplines, followed by a broader discussion of concepts for resilience.

The semester long course also provides sessions by disciplinary experts to address how systems fail due to threats from cybersecurity, human error and complex interdependencies. In addition, promising concepts that are being investigated to make these control systems more resilient to these threats are discussed. Students are challenged with mentor-guided projects that allow them to creatively enhance resilience to a power grid by designing their own enhancements. These enhancements will add improved operation, which enables students to understand how their skills can be used to address the real-world challenges of the power grid.

The book/course benefits include the following:

- Establishing an understanding for students of the unique and complex cognitive, cyber-physical and control challenges of automation in our society.

- Providing insight on how a power control system works and how it can fail—including threats from cybersecurity, human error and complex interdependencies.

- Teaching introduction to promising concepts that the resilient controls community is currently researching to make these control systems more resilient to these threats.

- Giving students an appreciation of the interdisciplinary nature of critical infrastructures and the beginning of skills required to converse in the “languages” of some of those disciplines.

- Mentoring students in projects that engage in the areas of resilient control systems as demonstrated through project papers and presentations.

- The text also includes special topics discussion of the intersection of metrics with policy to confirm benefits of investment. ◉

REFERENCES

[1] C. G. Rieger, D. I. Gertman and M. A. McQueen, “Resilient control systems: Next generation design research,” 2009 2nd Conference on Human System Interactions, Catania, Italy, 2009, pp. 632-636.

[1] S. M. Rinaldi, J. P. Peerenboom and T. K. Kelly, “Identifying, understanding, and analyzing critical infrastructure interdependencies,”

in IEEE Control Systems Magazine, vol. 21, no. 6, pp. 11-25, Dec.

2001.

[1] “August 2003 Blackout,” Department of Energy, Office of Electricity, https://www.energy.gov/oe/august-2003-blackout, accessed November 10, 2024.

iv Craig Rieger, “Multi‐agent Control Systems,” in Resilient Control Architectures and Power Systems, IEEE, 2022, pp.259-274.

[1] C. G. Rieger, “Resilient control systems Practical metrics basis for defining mission impact,” 2014 7th International Symposium on Resilient Control Systems (ISRCS), Denver, CO, USA, 2014, pp. 1-10.

[1] Sivils, P., Rieger, C., Amarasinghe, K., Manic, M. (2019). “Integrated Cyber Physical Assessment and Response for Improved Resiliency.” In: Cicirelli, F., Guerrieri, A., Mastroianni, C., Spezzano, G., Vinci, A. (eds)

The Internet of Things for Smart Urban Ecosystems. Part of Internet of Things book series. Springer.

Craig Rieger, PHD, PE, Managing Director & Consultant at TRECS Consulting

Craig Rieger, PhD, PE, is the Managing Director and Consultant at TRECS Consulting. Previously, he served as the Chief Control Systems Research Engineer and a Directorate Fellow at the Idaho National Laboratory (INL), pioneering multidisciplinary research in next-generation resilient control systems. In addition, he has organized and chaired 14 Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) technically co-sponsored symposia and one National Science Foundation workshop in this new research area. He has authored more than 50 peer-reviewed publications. Dr. Rieger received his BS and MS degrees in Chemical Engineering from Montana State University and his PhD in Engineering and Applied Science from Idaho State University. His doctoral coursework and dissertation focused on measurements and control, with specific application to intelligent, supervisory ventilation controls for critical infrastructure. Dr. Rieger is a senior member of IEEE with 20 years of software- and hardware-design experience for process control-system upgrades and new installations. He has also been a supervisor and technical lead for control-systems engineering groups having design, configuration management and security responsibilities for several INL nuclear facilities and various control-system architectures.