For decades, the stereotypical “gamer” was a solitary player sitting in a dark room, locked away from the real world and locked into a digital one. Today, gamers are more likely found on college campuses engaging in collegiate esports, which has become a booming industry, turning colleges and universities worldwide into training grounds for new generations of competitive gamers.

The term “esports” (aka, “e-sports” or “eSports”) refers to competitive video gaming in which players—most often playing as teams—compete against each other. Instead of staying at home or sitting in their dorm rooms, today’s gamers are coming together on college and university campuses to form esports clubs and join competitive teams.

While competitive video gaming has existed since at least the 1980s, the term “esports” was coined in 2000 and derives from shared characteristics with athletics programs, including an emphasis on developing well-rounded leaders through teamwork, strategic thinking, precise timing and adaptability.

By leveraging video games as a platform, esports programs offer a new and unique set of opportunities for students to compete and get involved on their campus. One student at Minot State University (MSU) noted that after a car accident “took away my ability to be competitive and belong to something [in sports], esports came along and gave me the chance to do that again in school.”

Although far less physically intensive than sports, many esports competitions take place in annual seasons like sports, and collegiate esports competitors often have student contracts similar to those of student-athletes that specify expectations for academic progress, wellness activities and team practices.

Esports programs are becoming increasingly common at campuses throughout the North Dakota University System (NDUS), as well as in public and private high schools, private universities and other organizations statewide.

Supported by a rapidly growing industry that includes video game developers, computer hardware companies and sponsorships, NDUS institutions are building competitive programs, inclusive student communities, academic programs of study, research agendas, policy proposals and regional tournaments for both high-school and collegiate players. With more than 150 MSU students (or roughly 6 percent of the student body) involved in esports and 30 (about 1.2 percent) competing on varsity esports teams, esports programming engages a proportion of the student body that’s comparable to most individual sports programs.

The authors, Professor Ethan Valentine and Briana Romfo, lead the MSU esports program. Romfo is a 2024 MSU graduate with a B.A. in Elementary Education, a former competitive Valorant[i] player for the university, and MSU’s current Esports Head Coach. Valentine is an Assistant Professor of Psychology and serves as Director of MSU Esports and faculty advisor for the esports club.

Global Phenomenon

Global revenues in esports are projected to reach $4.8 billion in 2025.[ii] This includes revenues in media rights and broadcasting, merchandise, ticketing for live events, game publisher fees, advertising and esports betting. Although often thought of as a purely digital pursuit, esports is rooted in face-to-face competitions hosted in arcades, including events such as Sega’s All Japan TV Game Championships in 1974 and Atari’s 1980 Space Invaders Championship in the U.S.[iii]

With the advent of online play throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, competitive gaming has only continued to grow. South Korea was a focal point for this early growth, with the Korean e-Sports Association formed in 2000 as part of the South Korea’s Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism.[iv] As the popularity of esports has grown, so too have viewership numbers and prize pools for professional tournaments. The 2023 League of Legends World Championship saw peak concurrent viewership of around 6.4 million fans, with total viewership likely much higher, and a prize pool of more than $2.2 million.[v]

It also seems likely that competitive gaming has a long life ahead, given that 85 percent of 13- to 17-year-olds report playing video games.[vi] Demographics are shifting as well: Among those who self-identify as gamers, roughly 46 percent are women, up from 38 percent in 2006.[vii] In this changing landscape, collegiate esports programs are quickly becoming a staple nationwide.

Collegiate Esports

Just as the professional esports industry has set revenue and viewership records in recent years, the collegiate esports ecosystem continues to boom. While chess and other gaming clubs have existed on college/university campuses for decades, the earliest varsity esports programs (funded by their colleges) in the U.S. date back to around 2015 at Robert Morris University in Illinois.

Today, there are more than 750 collegiate esports programs in the U.S. with about 40 percent of the programs housed in athletics departments, 15 percent in academic departments and 45 percent in student services departments. This growth reflects the desire on the part of both colleges and students for increased engagement and esports’ capacity to increase enrollment, which is needed throughout higher education.

In 2023, about 60,000 students enrolled in esports programs nationwide,[viii] compared to half that number in 2020,[ix] with programs reporting an average addition of 10 to 15 new esports players in 2023. About 90 percent[x] of esports participants are male, offering an opportunity for colleges and universities to address the falling enrollment in recent decades among male students, more of whom might choose higher education if informed about esports programs. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, there are about 700,000 fewer men than women in post-secondary institutions.[xi]

On the financial side, approximately $46 million in esports scholarships were distributed during the 2023-24 academic year against total tuition revenues of over $1 billion for students enrolled in esports programs. Sponsorships and donations further support these programs, with fundraising averaging $14,726 per year, with some of the most successful programs raising more than $100,000 per year in sponsorships and donations.

While campuses might invest primarily to grow and retain their student bodies, students become invested in esports for a number of reasons. The roots of many collegiate esports programs are in student clubs, which highlight one of the major benefits: a community of peers with similar interests. Esports clubs and programs serve a population of students who has often struggled to find a community on college campuses, given that their interests and hobbies have often depended on online—rather than in-person—communities. Typical comments from MSU students, for instance, note that esports programming “helps me feel more connected to campus” and “makes it easier to make friends with similar interests.” Students also directly benefit from scholarships that reduce their cost of attendance, which is a huge benefit given the cost of a college education today.

In addition, esports programs help develop crucial skills among their competitors, including teamwork, critical thinking, problem-solving and emotion/stress coping.

Challenges

Despite the many positives, collegiate esports programs face several challenges. Programs are—perhaps understandably—under pressure to grow student bodies and support an ever-growing number of competitors. That growth leads to difficulties with infrastructure, since few institutions have the funds to support increasingly large competitive programs. Costs to grow an esports program include expensive PCs, which need to be replaced every few years, and paying higher electrical bills, which might include rewiring facilities, and increased bandwidth usage, which IT departments must account for.

Many programs also struggle to establish a sense of legitimacy on their campuses and in their communities, with competitive video gaming sometimes viewed as less valuable than traditional athletics and even inappropriate for institutions to support due to the controversy about the impacts of violence in video games. In contrast, many video games played in collegiate (and high school) esports spaces are not explicitly violent, or they are built to be inherently fantastical and unrealistic. Games such as Rocket League (think soccer, but with rocket-powered cars) and League of Legends (a fantasy world in which players capture territory and slay dragons) dominate many esports competitions, while first-person shooter games such as Valorant avoid showing blood and gore.

In addition, while the evidence on the effects of violent media is mixed, recent research suggests that video game play may be related to positive mental health,[xii] pro-social behavior[xiii] and many of the other benefits of traditional sports[xiv] when gameplay is well managed, as it can and should be in collegiate programs. Even the U.S. military is on board, with gaming and esports being used for both recruitment[xv] and combat readiness.[xvi]

Part of this struggle with legitimacy comes from the lack of a uniform competitive structure. While organizations such as the National Association of Collegiate Esports (NACE) and the National Esports Collegiate Conference (NECC) largely dominate collegiate competitions, they—and all organizers—are inherently limited in the rules and regulations they can create due to software publishers owning the games. If Riot Games (publisher of League of Legends and Valorant), for example, institutes a new rule, all organizations must comply or not compete. By contrast, sports organizing bodies such as the National Collegiate Athletic Association don’t have this problem as no one organization “owns” basketball, football or other sports.

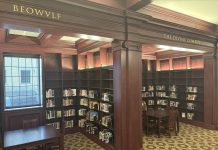

Great Plains Gauntlet, hosted by Minot State University.

Perhaps most important from a day-to-day perspective is the issue of burnout. Many collegiate program directors and coaches are heavily overworked, with individual coaches often managing five or more esports games at a time. For example, Briana Romfo (the coauthor of this article) coaches players in five games—Valorant, League of Legends, Overwatch 2, Rocket League and Super Smash Bros. In the spring semester, either or both Call of Duty and Apex Legends will be added to her workload.

“Each game requires very different skills and knowledge to be successful, both as a coach and a player,” explained Romfo. “Games such as Valorant and Overwatch require knowledge of different maps, quick reaction times and knowledge of how players’ roles and characters interact. Super Smash Bros. is a fighting game with a focus on split-second judgments of distance, speed and motion. League of Legends is much more tactical, with decision-making and planning taking on bigger roles.

“As a coach, not only are you trying to manage gameplay, but you also are finding tools to help students with their mental and emotional health. Esports can be very demanding, with constant pressure to win, develop strategies and organize practices. And that’s just for one competitive title. Many coaches have to juggle multiple titles, each with its own set of strategies and team dynamics. When a coach experiences burnout, it affects the success of the entire team.”

Esports in North Dakota

In 2016, the University of Jamestown founded the first esports program at an institution of higher education in North Dakota. Then, in 2018, Dickinson State University (DSU) became the first NDUS school to start an institutionally funded program. Today, esports programs thrive at MSU, DSU, the University of North Dakota (UND), North Dakota State University (NDSU), Bismarck State College (BSC) and at Sitting Bull College, an affiliated tribal college. As well, several campuses, including Valley City State University, Mayville State University, North Dakota State College of Science, Dakota College at Bottineau and Williston State College host esports clubs. Most in-state teams compete in leagues/seasons hosted by the NECC and/or NACE. As well, some teams compete in tournaments or leagues hosted by other organizers (for example, College Call of Duty and Collegiate Champions League). Much like traditional sports conferences, these organizers run competitive seasons throughout the academic year and sometimes summers, with competitions varying in length from weekend tournaments to seasons lasting an entire academic year.

Esports at the high-school level in North Dakota is also growing. While esports remain a club activity at the secondary level (as opposed to an officially sanctioned student activity), hundreds of students statewide are actively participating in esports competitions. Fenworks,[xvii] a Grand Forks-based company founded by a UND graduate, functions as one of the primary organizers for high-school esports competitions, including hosting a state tournament each spring. The 2024 tournament featured more than 400 competitors from more than two dozen schools in North Dakota and Minnesota. These events and other high school competitions, such as MSU’s Great Plains Gauntlet and BSC’s Winter Brawl, serve as important opportunities not only for high schoolers to compete, but also for collegiate institutions to recruit new students.

Esports Academic Programs, Research & Community Building

Esports contribute to higher education by helping prepare gamers for careers both within and beyond the sport; by attracting academic research, which expands our understanding of psychology, business, media production, and other fields associated with esports; and by fostering community among students.

Just as most collegiate basketball players or sprinters won’t become professionals in their sport, most collegiate esports players won’t become professional players. And just as college athletic programs, collegiate esports programs need to focus on preparing students for careers beyond competition. Participation in esports programs help students develop important skills, including problem-solving, decision-making, collaboration, adaptation to change and cross-cultural communication.[xvii]

Regarding research, MSU’s Digital Cognition Lab, which includes student researchers Sara Van Wickler and Alex Engel, alongside Principal Investigator Ethan Valentine, presented findings at the 2024 Esports Research Network Conference on the differences in beliefs about performance-enhancing drugs (PED) in esports and traditional sports.

The findings showed that opposition to PED use in traditional sports was nearly unanimous, with 93 percent of participants—out of 193 students, staff and faculty at American colleges and universities—indicating that drug use was unfair in sports. However, only 60 percent of survey participants said the same for esports. Open-ended participant responses suggest that the differences may be due to the belief that PEDs would not matter in esports due to a lack of physical activity. More research is needed to confirm why this is and what impact, if any, those differences in beliefs may have on usage behavior. This is especially important given that it is generally not physically enhancing drugs (for example, anabolic steroids) that might be of concern in esports, but rather psychoactive drugs (for example, stimulants).

With broader connections to the Esports Research Network,[xix] Esports Foundry,[xx] Voice of Intercollegiate Esports[xxi] and other organizations with a stake in academic scholarship, there have never been more opportunities for researchers within NDUS to build research agendas tied to gaming and esports.

Another important contributor to the success of college/university campuses is how well they foster a sense of community for their students. NDUS institutions often support intramural tournaments for students on campus, host gaming-themed movie nights and organize events to simply bring people together to game. Beyond our campuses, community events and collaborations with local partners, such as iMagicon[xxii] (Minot), ByteSpeed[xxiii] (Fargo/Moorhead), Fenworks (Grand Forks) and others lead to meaningful local engagement.

Here in Minot, MSU Esports works with iMagicon (a convention for fans of gaming, anime, science fiction) to support in-person community gaming nights. In April 2024, MSU worked with LeagueOS[xxiv] (a platform for hosting esports leagues and recruiting students) and Visit Minot (the city’s tourism board) to host the first annual Great Plains Gauntlet[xxv] esports tournament for both high school and collegiate competitors on MSU’s campus.

Elsewhere, as examples, NDSU coordinates the Dakota Collegiate Rocket League circuit every semester (including in-person playoffs), BSC hosts an annual high school tournament during the spring semester, the University of Jamestown runs a collegiate tournament in the fall, and DSU held a virtual esports conference for high school esports coaches for the first time this year.

Future of Esports in North Dakota

Despite the broad challenges facing esports—including coach burnout and infrastructure limitations—the future of collegiate esports seems bright. With an estimated two million high school esports players in the U.S. and a multitude of ways for our university system to engage with the esports landscape, we have new opportunities to continue to serve our students, our communities and our academic disciplines. Through partnerships within and between campuses, collaborations with community groups and innovative research agendas and programs of study, engagement with esports will continue to provide the NDUS with the chance to lead the way in education, research and community involvement. ◉

REFERENCES

[i] https://playvalorant.com/en-us/

[ii] Statista, “Esports—Worldwide,” Statista, March 2024, https://www.statista.com/outlook/amo/esports/worldwide.

[iii] Michael Borowy & Dal Yong Jin, “Pioneering E-Sport: The Experience Economy and the Marketing of Early 1980 Arcade Gaming Contests,” International Journal of Communication 7 (2013): 2254-2274.

[iv] Dal Yong Jin, “Historiography of Korean Esports: Perspectives on Spectatorship,” International Journal of Communication 14 (2020): 3727-3745.

[v] Esports Charts, “2023 World Championship,” Esports Charts, https://escharts.com/tournaments/lol/2023-world-championship.

[vi] Jeffrey Gottfried and Olivia Sidoti, “Teens and Video Games Today,” Pew Research Center, May 9, 2024, https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2024/05/09/teens-and-video-games-today/.

[vii] Statista, “Distribution of video gamers in the United States from 2006 to 2023, by gender,” Statista, July 2023, https://www.statista.com/statistics/232383/gender-split-of-us-computer-and-video-gamers/.

[viii] Postell & Narayn, “Trends in Collegiate Esports,” 2024.

[ix] Chris Postell & Kris Narayn, “Trends in Collegiate Esports,” Esports Foundry, Volume 1 (2020), https://esportsfoundry.com/Trends-in-Collegiate-Esports.html.

[x] Ruby Moley, “Women Underrepresented in Collegiate Esports,” The State Press, November 30, 2022, https://www.statepress.com/article/2022/12/women-underrepresented-in-collegiate-esports.

[xi] https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=98

[xii] Niklas Johannes, Matti Vuorre, & Andrew K. Pryzybylski, “Video game play is positively correlated with well-being,” Royal Society Open Science, 8 (2021): 202049.

[xiii] Daniela Smirni et al., “The Playing Brain. The Impact of Video Games on Cognition and Behavior in Pediatric Age at the Time of Lockdown: A Systematic Review,” Pediatric Reports, 13 (2021): 401-415.

[xiv] Nicholas David Bowman & Gregory A. Cranmer, “Can Video Games be a Sport? Debating and Complicating Esports as Physical Competitions,” in Understanding Esports: An Introduction to the Global Phenomenon, ed. Ryan Rogers (Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books, 2019), 15-31.

[xv] Katie Lange, “Military Esports: How Gaming is Changing Recruitment and Morale,” U.S. Department of Defense, December 13, 2022, https://www.defense.gov/News/Feature-Stories/Story/article/3244620/military-esports-how-gaming-is-changing-recruitment-morale/.

[xvi] Scott Kuhn, “Soldiers maintain readiness playing video games,” U.S. Army, April 29, 2020, https://www.army.mil/article/235085/soldiers_maintain_readiness_playing_video_games.

[xvii] https://fenworks.com/

[xviii] Bonilla, I., Chamarro, A., & Ventura, C. (2022). “Psychological skills in esports: Qualitative study of individual and team players.” Aloma, 40(1), 35-41. Zhong, Y., Guo, K., Su, J., & Chu, S.K.W. (2022). “The impact of participation on the development of 21st century skills in youth: a systematic review.” Computers & Education, 191, 104640. Scholz, T.M. & Tan, C. (2024, October 30). “Transferrable skills from esports to international business environments: An intercultural management perspective.” Paper presented at the 2024 Esports Research Network Conference, London, UK.

[xix] https://esportsresearch.net/.

[xx] https://esportsfoundry.com/.

[xxi] https://www.voicecollegiate.org/.

[xxii] https://imagiconnd.com/.

[xxiii] https://bytespeed.com/.

[xxiv] https://leagueos.gg/.

[xxv] https://msu.leagueos.gg/.

Ethan P. Valentine, PhD, Professor of Psychology, Minot State University

Ethan P. Valentine, PhD, is an Assistant Professor of Psychology at Minot State University and the Director of Minot State Esports. Professor Valentine leads Minot State’s Digital Cognition Lab, where his research focuses on how we think, learn, and connect within digital and mixed physical/digital spaces. His work includes explorations of user choice in open education, the role of online communities in providing social support, the design of location-based augmented reality for spatial learning and the use of performance-enhancing drugs in esports. Professor Valentine frequently teaches coursework in statistics and research methods, as well as his own interest areas in the science of learning and cyberpsychology. He earned his MA and PhD in Psychological and Quantitative Foundations from the University of Iowa.

Briana R. Romfo, Esports Head Coach, Minot State University

Briana R. Romfo is the Head Coach of the Esports Program at Minot State University and a collaborator in the Digital Cognition Lab's research into how digital tools, including games and virtual reality, support learning and mental model development. Romfo previously held the position of Vice President of the Minot State Esports Club and served as the captain of the Minot State Valorant team, competing for three competitive seasons. She also led the organization of Minot State’s first annual Great Plains Gauntlet esports tournament. With experience as both a competitor and a coach, Romfo is committed to helping new players grow and develop leadership skills and mental resilience. She holds a Bachelor of Science in Education (BSE) in Elementary Education from Minot State University.