Can you read this article from start to finish without picking up your phone? The odds are against you.

Our devices are constantly beckoning us, our brains lighting up at the sight of notifications or the sound of our phone buzzing nearby. Even those of us who have resolved to avoid the distraction of our phones to be more present with family and friends still find ourselves spending large chunks of time on social media such as Facebook, Instagram and TikTok. We open the app without really thinking about it. We spend hours scrolling through content when we intend to spend just a few minutes decompressing from a stressful day.

The good news is that this behavior is not a personal failure on your part, as many people experience it. The bad news is that it is incredibly difficult to limit the use of algorithmically driven social media through willpower alone. We need deeper structural changes.

As a researcher, college instructor and parent, I spend a lot of time thinking, talking and writing about the social impacts of technology. In my research, I study how people integrate, negotiate and make rules for using new communication technologies, such as Zoom or TikTok. In my classes at North Dakota State University, I teach students how to use emerging technologies, such as ChatGPT and other AI tools more ethically and effectively.

The impact of technology on young people is also personal for me—having two elementary-aged kids who love playing video games and watching funny cat videos online. Our family has frequent conversations about how to balance screentime with the other activities that help children learn and develop. My husband and I have learned to speak up when we feel we are competing with the phone for one another’s attention. You may be having similar conversations with your children, partner or colleagues.

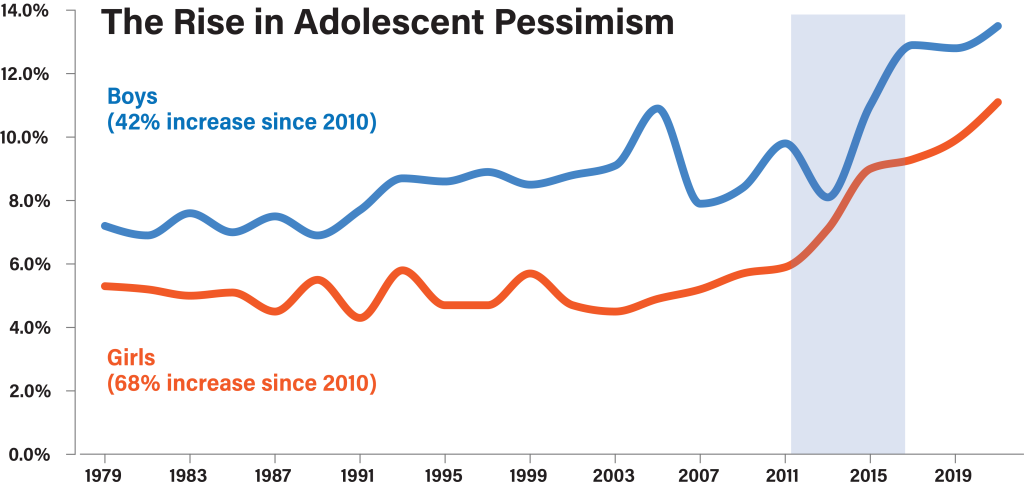

These everyday conversations on the promises and perils of new technologies reflect a broader societal turn from viewing mobile phones and social media as democratizing technologies that will empower all users. We are becoming more aware of the social costs we pay for living in a world of 24/7, user-generated content. In response to an increasing body of research linking social media use and rising rates of anxiety and depression amongst adolescents, the U.S. Surgeon General has called for warning labels on social media platforms. California is seeking to ban the use of phones in public schools across the state.

There may not be a direct correlation between social media and anxiety or depression. Many researchers studying the impact of social media on younger people point to how social media consumption and online interactions displace activities that are known to contribute positively to mental health, such as physical activity, spending time outside and interacting with others face-to-face. But the distraction of social media, its impact on our ability to focus or tolerate boredom, is difficult to deny. We can feel this change, firsthand, in the speed with which we switch our attention away from a challenging task at work or pick up our phones when waiting in line. Understanding what makes social media so hard to resist is the first step in taking control of our attention back from these platforms and focusing on what really matters.

Algorithmically Driven

Social media platforms, such as YouTube, Instagram or TikTok, are unique in that the content you see is algorithmically-drive. In the simplest terms, social media platforms operate as giant recommendation engines. They collect data about your behavior—what you click on, how long you linger on a post, what you like, share and comment on—to create a profile of your interests. Then they use complex algorithms to analyze this data and predict what content you are most likely to engage with in the future. The more time you spend on the platform, the more ad revenue the platform generates. As the saying goes, “If you are not paying for the product, you are the product.”

So, when you open your social media feed, what you see is not random. It is carefully curated based on what the algorithm predicts you will find interesting or engaging. This personalized content keeps you scrolling because it is tailored to your preferences, which can make it hard to resist spending more time on the platform. Moreover, these algorithms are designed to continuously learn and adapt, refining their understanding of your interests over time. This means the more you use social media, the better it gets at showing you content that grabs your attention, and the harder it is to control your own use.

Goals vs Effects

We start using social media with the best of intentions. We see it as a valuable tool for making new social connections, maintaining our existing relationships, learning about the latest trends or current events. We use platforms such as Instagram and TikTok for entertainment—a break from our work or means of decompressing at the end of the day. But the more time we spend on social media, the more susceptible we become to the social costs of increased technology use. Research points to worrying mental health effects associated with increasing levels of loneliness, feeling disconnected from family and friends, social comparison, body image issues and misinformation, all of which may accelerate with the advancing capabilities of generative AI.

In essence, we adopt new technologies to achieve specific and positive goals, but we often end up feeling lonely, misinformed, discouraged by social comparison or distracted from our work. And then we struggle to disentangle ourselves in the face of deeply engrained psychological and social factors. Our human craving for novelty is continually fed by the dopamine our brains release as we scroll through our feeds. We experience a fear of missing out, of losing our main source of social monitoring, of damaging the personal and professional networks we worked so hard to build. But the reality is that there are many ways to fulfill these needs that do not involve spending hours looking at social media on our phones.

If you take the time to articulate your core values and identify your most important commitments, you can identify the ways that technology helps and hinders you.

Strategies for Intentional Use

I am not advocating for complete avoidance of social media. I use Instagram to keep up with family and friends. I enjoy watching funny videos on YouTube with my children. But I strive to be intentional in my mindlessly picking up the phone and scrolling. There are four strategies I have found to be helpful for those, like me, who want to use social media in a limited way.

Strategies to limit social media:

- Increasing friction: With this strategy, you add more steps needed to check social media. It involves removing social media apps from your phone, using blockers to keep yourself away from the site during certain time periods and removing the auto-login or auto-fill password, so you must enter it each time you want to access the site. The greater mental effort required to access the site gives you more time to think about whether you are using technology with intention or just out of habit. Social media platforms are continually trying to reduce the amount of time it takes you to access their content, which is why they encourage you to “stay logged in,” use their app instead of browser interfaces and enable push notifications. This strategy can help if you want to stop checking social media out of habit or avoid using your phone when you are around other people.

- Setting explicit boundaries for use: This strategy includes unfollowing people or restricting your posts to certain topics, as well as maximizing the social media behaviors that have been found to generate more happiness and satisfaction, such as commenting on the posts of people we know and reminiscing by looking back through our own feeds. Some people only allow themselves to check social media feeds during certain times of the day. I personally avoid social media right after waking up, because I do not want it to set the tone for my day, and in the late evening, because I know it interferes with sleep. Many people have found success using the “phone foyer” method, where they place their phone in a specific and harder-to-access location in their home rather than carrying it around in their pocket or sleeping with the phone next to them. This strategy helps people who compulsively check social media because they have a fear of missing out on something important.

- Identifying & assessing the underlying need/emotion: This strategy involves asking yourself why you are checking social media and whether doing so will help you to satisfy the need or process the emotion you are experiencing. Most people—myself included—open a social media app because we are feeling lonely, bored or frustrated with something difficult we are trying to do. There are some types of interactions on social media that can alleviate boredom, but the negative emotions associated with passive consumption typically outweigh the novelty offered by our social media feeds, leaving us feeling like we have eaten a bunch of junk food. Asking yourself what you are feeling and what you need to address that feeling can move you toward more restorative activities that involve greater engagement with your body, your physical environment and the people who exist outside of your phone.

- Creating if-then scenarios: This strategy focuses on the preemptive creation of alternatives to social media. It involves envisioning what you want (more intentional or less frequent social media use), brainstorming the most likely obstacles to achieving this goal and identifying a specific action you will take when you encounter those obstacles. That might look like: “If I find myself opening social media because I’m bored or waiting on something, then I will switch over to the Kindle app and read a novel;” or “If I am checking social media because I feel lonely, then I will message a friend;” or “If I am checking social media to avoid a task, then I will take a short walk around the office instead.” This strategy helps you address underlying needs while adding higher-value activities back in your day.

Navigating the complexities of social media requires a thoughtful, intentional approach. As new technologies continue to emerge and social media platforms find new ways to capture our attention, it becomes increasingly important to reclaim control over our digital lives. Strategies such as those above help us foster a healthier relationship with social media. More and more people are choosing to opt out of social media all together. Whatever you choose, I encourage you to begin by reflecting on what truly matters to you, rebalancing the benefits of technology with the richness of offline experiences. Together, we can shape a future where our digital tools enhance rather than control our lives. ◉

Carrie Anne Platt, PhD

Carrie Anne Platt, PhD, is a Professor of Communication and Vice Provost for Faculty Affairs at North Dakota State University. She received her PhD in Communications from the University of Southern California, her MA in Communications from Wake Forest University and a BA in Communication Studies & Public Relations. Platt’s research focuses on how we make sense of emerging technologies and establish norms or rules that guide their use. Her published work appears in the Journal of Medical Internet Research, the Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, and Public Understanding of Science. Platt’s Shadow a Student Initiative was featured by the Fargo-Moorhead Forum and The Chronicle of Higher Education.