Cyberattacks on critical industrial infrastructure, such as power plants, pipelines and refineries, risk more than the loss of trade secrets, contract negotiations and employee data. Worst-case attacks risk long-term damage to equipment, casualties at industrial sites and even impacts on the environment and public safety. The most serious attacks target operational technology (OT) systems—the computers that automate and control our industrial infrastructure’s large, powerful physical processes.

A big problem for defenders of such systems is that any change to safety-critical systems, even upgrades to cybersecurity protections, take a long time because of the testing required. Every change to safety-critical or reliability-critical systems risks introducing errors or omissions that impair operations. Practically, this means owners and operators of this kind of infrastructure must look some distance into the future to anticipate threats, so that we can design today’s defenses to be capable enough to address both today’s threats and those threats that will emerge, before we have the opportunity to design, test and deploy any security program upgrade.

The changing threat environment complicates OT defenses: More powerful attack tools and techniques continue to be invented and deployed against both IT and OT targets by everyone from politically motivated hacktivists to ransomware criminal groups and nation-state sponsored intelligence agencies and militaries. Cyberattacks that most organizations were able to dismiss as not credible, since only remotely possible, a decade ago, are now actual. We’ve seen them happen.

Defenders of systems that pose potential threats to public safety and national infrastructure/security have professional, ethical and often legal obligations to deploy reasonable defenses that are able to defeat with a high degree of confidence all credible threats of unacceptable consequences.

In this article, we explore the state of the practice: The evolving threat environment, how our understanding of cyber defenses for OT systems is evolving, and the latest innovation in robust OT cybersecurity, which is the Cyber-Informed Engineering initiative at the Idaho National Laboratory.

Credible Threats & Consequences

In the last five years, we’ve seen a deteriorating threat environment physically impacting industrial control systems and critical infrastructure operations around the globe.[i] Before 2019, incidents causing production delays, plant shutdowns, equipment damage or worse occurred at most once or twice per year. In the last two years we’ve seen almost 150 such incidents in the public record. Eighty-five percent of these attacks in the last five years were perpetrated by criminal ransomware groups. Nearly all the rest were perpetrated by politically motivated hacktivists and nation state militaries and intelligence agencies.

Politically or militarily-motivated attacks are growing in severity, with a 250 percent growth over the last three years and the discovery of three new OT-specific malware strains in 2024 alone. Also, credible evidence has emerged that hacktivists and nation-state actors are sharing these malicious tools, techniques and procedures (TTPs).[ii]

An Evolving Understanding

To address cyberthreats to critical infrastructures and other industrial operations, the first generation of cybersecurity standards and guidance, issued shortly after the 9/11 attack on the World Trade Center, was based on advice from IT experts. This made sense at the time in that enterprise security teams had been dealing with cybersecurity threats for several decades and were, therefore, the logical experts to contribute to the task of securing OT systems. The key principle underlying this generation of advice is that, in computer systems, information is almost always the key asset we must protect. And so, IT experts advised engineering teams and other OT security practitioners to protect their information: the confidentiality, integrity and availability of the information in their industrial automation systems.

This confused a great many practitioners. Once engineering teams gained some experience with cyberattacks and defenses, engineers developed second-generation advice, recognizing that, yes, in some cases there is valuable information in OT systems that must be protected from cyberespionage. In most cases, however, it is the physical process itself that is the key asset deserving of protection from cyber-sabotage: the dams, generators, pipes, pumps and distillation towers of our critical infrastructures.

The primary goal for most OT cybersecurity programs is not to protect information, but rather to assure safe, reliable and efficient operation of the physical process, and prevent damage to physical equipment—that is, damage serious enough to cripple the process for months rather than hours.

The key difference between preventing espionage and preventing sabotage concerns the focus on information. An industrial automation system can change from a normal mode of operation to a compromised or sabotaged mode, only if cyber-sabotage attack information somehow enters and impairs the system. All cyber-sabotage attacks involve information, and all information flows are potential attack vectors. Whereas IT cybersecurity is focused on protecting information, OT cybersecurity programs must focus on protecting physical infrastructure from information, more precisely from cyberattack information that might be embedded in other information flows.

Cyber-Informed Engineering

Today, a third generation of insight and advice is emerging, led by the Cyber-Informed Engineering[i] (CIE) initiative funded by the U.S. Department of Energy and carried out by researchers at Idaho National Laboratory. Informally, Cyber-informed engineering positions OT security as ‘a coin with two sides.’ One side of the coin is IT-style cybersecurity, focused on teaching engineering teams about cyberattacks, cybersecurity tools and mitigations, and the intrinsic limitations of each of these tools and mitigations. The other side of the coin is engineering: teaching enterprise security teams about powerful engineering tools that can address all threats to physical operations.

The nature of these engineering tools depends on the industry and on the physical process in question. For example, if you were a technician responsible for a half-dozen massive catalytic crackers in a large refinery—massive devices full of hot, high-pressure hydrocarbons—you would work most of every day within the kill radius of a worst-case cracker explosion. If one of these devices explodes, you will most likely perish.

Given that, how would you prefer to be protected from a cyberattack that overheats the furnaces under your crackers, over-pressurizes the crackers and causes them all to explode? Would you prefer a mechanical overpressure relief valve that, when the pressure of high-temperature hydrocarbons in the cracker is too great, the valve is mechanically forced open by that pressure and releases the hydrocarbons harmlessly into a flare stack? Or would you prefer a longer password on the computer controlling the furnace?

Most people answer they would prefer the mechanical relief valve. After all, the valve has no CPU and is thus in a real sense “unhackable” in a cyberattack. Experts respond that not only would they want the unhackable mechanical relief valve, they would want four such valves, because these mechanisms do wear out with metal fatigue and corrosion. Experts would want at least one of the valves to work to save their lives. And they would want a longer password. And they would want an absolute “boatload” of other IT-style cybersecurity protections, because, after all, their lives are on the line.

The experts’ answer is correct and supported by cyber-informed engineering. Although, every coin has two sides, when we spend a coin, we don’t choose which side to spend; we always spend the whole coin.

More specifically, cyber-informed engineering is an umbrella term, assembling a body of knowledge that includes cyber-relevant aspects of safety engineering, protection engineering, automation engineering, network engineering, as well as OT-relevant aspects of cybersecurity, including all the pillars of the National Institute of Standards and Technology and Cybersecurity Framework: Govern, identify, protect, detect, respond and recover. Cyber-informed engineering includes engineering tools that were neglected in the first two generations of cybersecurity advice, in addition to key elements of the engineering perspective on risk management.

In addition, cyber-informed engineering reflects how engineering teams deal with physical risk. For example, when safety engineers look at a refinery or pipeline, the first question they ask is not, “What are the most frequent, least-consequential incidents we see every day?” The first question they ask is, “What are the ‘big fish,’ the truly unacceptable outcomes that we must prevent at all costs?”

Similarly for cyber protection of industrial processes, cyber-informed engineering encourages us to address these questions:

- What are the very worst consequences that can possibly be caused by mis-operating the physical process, and are those consequences acceptable?

- If they are not acceptable, are there credible cyberthreats that could bring about those consequences?

- And if yes, what are reasonable measures to deploy to defeat those threats and attacks with a high degree of confidence?

This is the same style of analysis engineering teams carry out routinely to prevent casualties, disasters, equipment damage and costly downtime due to fires, floods, hurricanes, earthquakes and other physical threats. Cyberthreats are unusual in this analysis primarily because of how quickly the threats are changing. While safety and equipment protection analyses tend to be fairly static over the life of an installation, cyberthreats demand regular reassessment and demand deploying protections that have a large margin for any errors made in assessing the risk.

Innovation Needed

A common criticism of the emerging cyber-informed engineering body of knowledge is that many of the key engineering mitigations, such as overpressure relief valves and centrifugal overspeed governors, are old. Most of these mechanisms have been replaced by digital Safety Instrumented Systems (SIS) over the course of the last decade, because the digital systems are both cheaper and more reliable than the electromechanical safeties they replace. Yes, SIS are software, and yes, all non-trivial software has defects and vulnerabilities that attackers might exploit, so digital safeties are intrinsically more vulnerable to cyberattacks than electro-mechanical safeties, but going back to less reliable and more expensive electro-mechanical tools does not seem like progress.

The criticism is valid. What cyber-informed engineering teaches us, however, is to ask different questions. The question, “How can I use IT-grade cybersecurity designs to achieve engineering-grade protections?” has no answer. The question cyber-informed engineering asks instead is, “Well, if you don’t like existing engineering-grade protections, how can you make modest changes to the design of your system to address the risk another way?”

Innovation in Action

For example, consider rooftop solar inverters, which convert direct current (DC) coming from solar panels into alternating current (AC) that is compatible with household needs and with the grid at large. The inverters carry out a number of safety-critical functions, including:

- converting DC to AC power;

- converting the power from panel voltage to grid voltage;

- detecting when the grid has no power (is in an “island” mode) and then stopping sending power into that part of the grid, which might have repair workers touching it;

- detecting overheating of the inverter and then shutting off the flow of power before a fire can start.

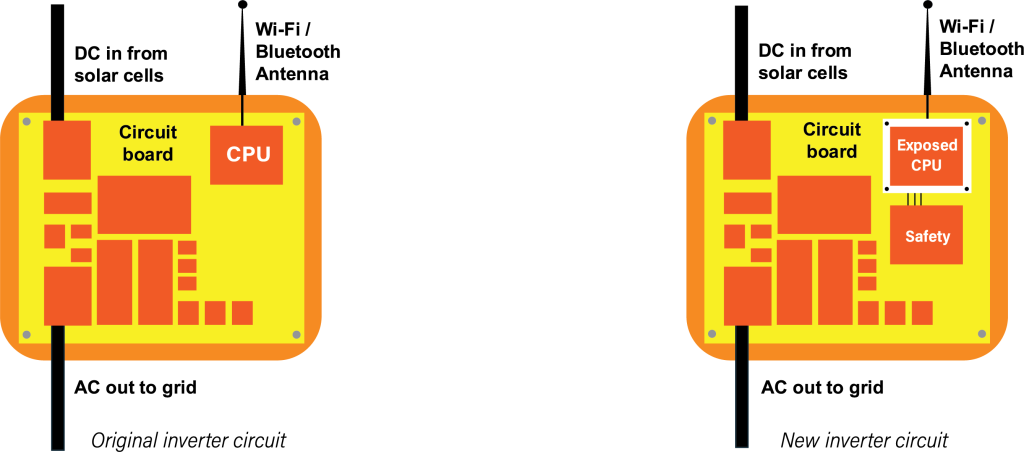

In the latest generation of converters, all these functions are carried out in silicon on a circuit board under the direction of software. There are no longer anyanalog transformers or other electro-mechanical components in the devices. This design lets manufacturers produce a single inverter model that can be configured in software and certified for use in many countries, each with different grid voltages and frequencies.

This flexibility introduces cyber-risk, however, since these modern devices have built-in Wi-Fi and Bluetooth connections to the internet, cell phones, and other devices and systems. This is a lot of software, with inevitable defects and vulnerabilities, and this software is exposed to network connectivity and even to interactions with the open internet. The inverters are therefore very much at risk of being compromised in a cyberattack.

A compromised inverter risks mis-operating the safety-critical functions of the device, either at the attackers’ bidding or indirectly because of lack of understanding by the attackers of the device they are manipulating. For example, a compromised device can be configured in software to send the wrong voltage into the grid. This results in the device overheating dramatically. A compromised device may also impair over-temperature safety shutdown function. If the device is mis-operated and becomes much too hot, it simply bursts into flames and risks burning down the building to which it is mounted.

The solution here is not to return to analog transformers, electro-mechanical over-temperature relays and other “old” technologies. The solution is innovation, for example, by adding another CPU to the inverter. Put the Wi-Fi, Bluetooth and other network-exposed functions on a separate “exposed” and, to a large degree, expendable CPU. Design the circuit board so that this CPU is the only one exposed to attacks from wireless networks and the internet, and so that this CPU is electrically unable to send any signal to any of the safety-critical devices. Put the safety-critical software on the second “safety” CPU that is the only CPU able to interact with the safety-critical hardware.

And finally, put an extremely limited communications interface between the two CPUs. Do not send messages between the CPUs, since most messaging communications protocols can become confused and propagate compromise from the exposed CPU into the safety CPU. This is called “pivoting” a cyberattack, when our enemies use a compromised computer (the exposed CPU) to attack connected computers (the safety CPU). Design the interface between the two CPUs to be so simple and deterministic that attack pivoting is not a credible threat to the device, not with today’s attacks nor with any imaginable future cyberattacks.

In this new design, what is the worst that can happen if the Wi-Fi/internet-exposed CPU is compromised? The inverter might stop reporting how much power it is feeding the grid or might not respond to islanding orders from the grid. All these consequences are acceptable. The grid has other ways to measure power flows and grid stability—reports from inverters are not reliability-critical. And even if the inverter does not receive an islanding order from the grid, because that exposed communication function has been impaired, the inverter’s hardware is still able to detect islanding conditions in the local grid, and the safety CPU can still respond to detecting such conditions by stopping the flow of power from the solar cells.

The cost of the solution? The circuit-board design and the software in the inverter both need modest changes, and the circuit board needs a second CPU, which is not a high-powered $500-$1000 device like the CPU in your latest cell phone. Instead, this is a cheap embedded CPU able to carry out very simple, very important safety decision-making. With safety systems, simpler is better. Leave the complexity in the existing internet-exposed CPU.

Consequence Boundaries

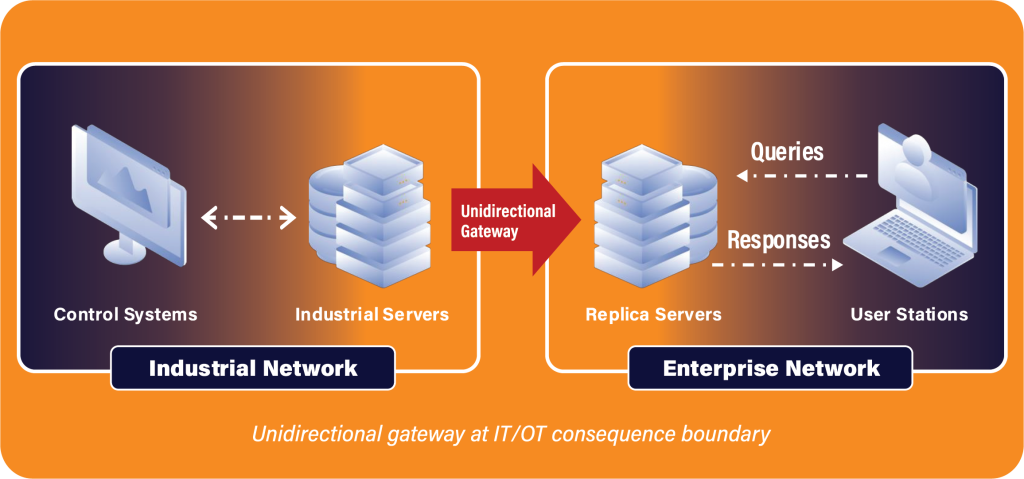

The solar inverter design is one example of a new field of knowledge. Emerging as part of cyber-informed engineering networks is a collection of techniques to deterministically prevent cyberattacks from pivoting across consequence boundaries. A consequence boundary is a connection between computers, or between networks of computers, whose worst-case consequences of compromise differ materially. The classic example of such a boundary is the so-called “IT/OT interface”—the connection between an IT network that automates business functions, such as purchasing or work-crew scheduling, and an OT network that automates and operates a physical process, such as a pipeline or power plant.

For example, what is the worst consequence a business suffers if a cyberattack compromises an IT network? Often, the worst case is that detailed information about thousands of employees is stolen, and the business needs to buy identity theft insurance for those employees at a cost of several million dollars per year. While such a loss is undesirable, it is not likely to put most organizations out of business. This is an undesirable, but acceptable loss.

On the other hand, what is the worst consequence a business suffers if a cyberattack compromises an OT network? Several examples:

- The worst-case mis-operation of a petrochemical pipeline can lead to a hydraulic hammer, which is a pressure wave that travels at the speed of sound in the fluid and risks rupturing the pipeline.

- The worst-case mis-operation of a high-speed metro switching system risks trains colliding at rush hour with hundreds of casualties.

- The worst-case mis-operation of a steam turbine in a large power plant risks the turbine shaking itself to pieces. The plant would then be unable to produce power for the nine to 12 months it takes to replace the turbine, at a cost of several hundred million dollars.

In short, the IT/OT interface very often connects IT networks with acceptable worst-case consequences of compromise to OT networks with unacceptable worst-case consequences.

For example, the Colonial Pipeline incident in 2021 shut down the nation’s largest gasoline pipeline for six days. A ransomware criminal group crippled part of the company’s IT network, and Colonial shut down the pipeline “in an abundance of caution.” Colonial’s management was not confident in the security of the OT network, given the nature of the attack impairing the IT network. They were not willing to risk the malware propagating from the IT network to OT automation, where it might cause a hydraulic hammer, pipeline rupture or other dangerous conditions.

Deterministic Defenses

A firewall is the most common security mechanism deployed between two networks. However, firewalls are not network engineering because they are not deterministic. While firewalls prevent some kinds of cyberattacks from propagating from one network to another, firewalls cannot prevent all such attacks from propagating. After all, how many IT networks were compromised by ransomware last year? While there is no universally accepted count, the number is certainly in the thousands and possibly tens of thousands. In the majority of these cases, the cyberattack came from the internet and pivoted through the organization’s IT-to-internet firewall to compromise the victim’s IT network and systems.

The solar inverter design is an example of intra-system network engineering. The most common example of network engineering at the IT/OT interface is unidirectional gateway technology[i]. A unidirectional gateway is a combination of hardware and software, by which the gateway’s hardware is physically able to send information in only one direction, generally from the OT network to the IT network. The software makes copies of servers and emulates systems, making OT data easily available to IT users and systems.

A unidirectional gateway permits useful data to move from OT networks into IT networks, whereby that data can be used to make the business more efficient. Crucially, the gateway is physically unable to propagate cyber-sabotage attack information, or any information, back into OT networks. Today, unidirectional gateway technology is widely used as deterministic protection at the IT/OT interface in the nation’s largest power plants, and it is used increasingly in petrochemical pipelines, refineries, passenger metros and the largest water treatment systems.

The Right Questions

Cybersecurity on IT networks is often seen as a game of one-upmanship. Every year, the attackers get a little better at what they do, which means the defenders also need to improve. Sometimes IT defenses fail, and victim organizations suffer millions of dollars in losses. The total of these losses across all businesses is significant: billions of dollars per year lost to ransomware alone. Generally, speaking, though, these losses are more or less acceptable to individual victims, in that very few victim organizations go out of business as a result of ransomware attacks.

In the physical world, worst-case consequences—worker casualties, threats to public safety and crippled critical infrastructures—can be truly unacceptable. Such losses currently do not happen routinely and must not be permitted to start happening routinely, despite worsening trends in sophisticated cyberattacks targeting critical infrastructures.

Cyber-informed engineering is a third-generation approach to the OT security problem, having much in common with how safety protection engineers look at protecting human life, the environment and long lead-time equipment.

Cyber-informed engineering does not currently and may never have all the answers we need, but fundamentally, it asks the right questions. Unlike IT defenses, cyber-informed engineering does not ask “How can I make my security system a little more effective, so that I might have a little more time to detect and hopefully defeat cyberattacks with unacceptable consequences?” “Hope” is not what we expect of design engineers. Cyber-informed engineering asks, “How can I design cost-effective, deterministic defenses that will prevent cyberattacks with truly unacceptable consequences with a very high degree of confidence, no matter how sophisticated such attacks become in the foreseeable future?”

While no defense is, or ever can be, perfect, we can dramatically increase the effectiveness of cyber defenses for our most dangerous and most important industrial processes and critical industrial infrastructures with cyber-informed engineering . Yes, cyber-informed engineering is new and is still a work in progress. Yes, we need innovation, especially in the field of network engineering, both to produce new designs, such as in the solar inverter example, and to deploy much more widely many existing approaches such as unidirectional gateway technology. But as the solar inverter example shows, modern cost-effective solutions can be invented for these needs. Engineering teams are certainly able to innovate and invent powerful solutions, but only if they are asked the right questions. Cyber-informed engineering, for the first time, asks the right questions. ◉

For a free copy of Andrew Ginter’s book, Engineering-Grade OT Security: A manager’s guide, you may contact Waterfall Security at: https://waterfall-security.com/engineering-grade-ot-security.

REFERENCES

[1] R. Machtemes, G. Hale, M. Walhof, A. Ginter and R. Clayton. “2025 OT Cyber Threat Report: Cyber Attacks with Physical Consequences,” Waterfall Security, March 2025.

[1] https://www.dni.gov/files/ODNI/documents/assessments/ATA-2023-Unclassified-Report.pdf

[1] https://inl.gov/national-security/cie/

[1] https://csrc.nist.gov/pubs/sp/800/82/r3/final

Andrew Ginter, Vice President, Industrial Security, Waterfall Security Solutions

Andrew Ginter is the VP Industrial Security at Waterfall Security Solutions and Founding Faculty at CambiOS Academy. Earlier in his career, Ginter led teams building industrial control systems products at HP, IT/OT middleware products at Agilent Technologies, and the world's first industrial Security Information and Event Management system (SIEM) as CTO at Industrial Defender. He is the author of three books on OT cybersecurity, most recently Engineering-Grade OT Security: A manager’s guide, and contributes regularly to industrial cybersecurity standards and guidance. Ginter earned a BS in Applied Math and an MS in Computers Science from the University of Calgary.

Rees Machtemes, Director Industrial Security, Waterfall Security Solutions

Rees Machtemes is a Director of Industrial Security at Waterfall Security Solutions, the lead threat researcher for the annual Waterfall/ICSStrive OT Threat Report and writes frequently on the topic of OT/ICS cybersecurity. Machtemes is a professional engineer with 20 years of experience with both IT and OT systems, having designed power generation and transmission substations, automated food and beverage manufacturing facilities, and audited and tested telecom solutions. He holds a BS in Electrical Engineering from the University of Alberta.