The unprecedented global prosperity over the past 200 years has been termed “The Great Enrichment” by Diedre N. McCloskey, Distinguished Professor Emerita of Economics and History at the University of Illinois at Chicago. Other economists have described it as the “Hockey Stick of Human Prosperity.” As a result of this economic surge, real per-capita income worldwide has increased by more than 1,500 percent since 1800, by more than 2,000 percent in the U.S. and by an astounding 4,900 percent in Japan.

Prof. McCloskey attributes this to “innovism,” the notion that ideas and creativity lead to prosperity more than the mere accumulation of capital. This resulted from a rise in liberalism, which increases freedom worldwide. Allowing people to pursue their own interests and to test their own ideas in the marketplace enabled the huge proliferation of ideas and the resulting innovations that have allowed us to live better.

Recently, the link between liberalism and innovation has been recognized in academic and business literature, particularly concerning the benefits of viewpoint diversity. Academic studies highlight the benefits of viewpoint diversity in driving innovation resulting from information exchange and elaboration among team members with different ideas. As noted by Entrepreneur Magazine, disagreement and differences of opinion lead to better ideas and innovation.

In discussing the benefits of diverse thinking, UC Berkeley ExecEd (Executive Education at the University of California Berkeley) notes that the 2012 Mars rover landing was facilitated by a team at the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) with a wide variety of viewpoints that blended traditional and novel ideas to achieve a groundbreaking solution.

[O]ver the four years of our survey, large percentages of students have consistently said they favor illiberal actions regarding speech.

This liberal environment in the U.S. has made it a global leader in innovation, ranking third in the world on the Global Innovation Index—the measure of innovation capability and success developed by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO).

However, this liberal environment is under attack, with calls for regulating or censoring social media from the left and the right, as well as growing illiberalism on most campuses.

Challey Institute & College Pulse Survey

To gain a better understanding of the degree of liberalism or illiberalism on college campuses, the Sheila and Robert Challey Institute for Global Innovation and Growth at NDSU, in collaboration with College Pulse (an online survey research and analytics company focused on U.S. college students), has conducted a survey of university students nationwide since 2021 on issues related to viewpoint diversity and campus freedom.

The survey explores the classroom climate, students’ comfort level in sharing opinions, their attitudes toward unpopular or controversial points of view or speakers, and their willingness to report others who offend them.

On the surface, the survey results from the past four years suggest a campus environment that welcomes diverse views and allows students to express their opinions on controversial and sensitive topics. From 2021 through 2023, more than 75 percent of students reported a classroom climate that allowed diverse points of view and where professors encouraged a wide variety of viewpoints, and more than 63 percent reported a classroom climate in which people with unpopular views would feel comfortable sharing their opinions.

Although our 2024 survey didn’t ask the same questions, it shows that 70 percent of students feel at least somewhat comfortable sharing their opinions on controversial or sensitive topics in class. These results suggest an environment of free inquiry and contestation of ideas that enables universities to fulfill their missions of advancing scientific knowledge and training students in critical thinking.

Openness Illusion

However, a closer look reveals that this apparent openness is an illusion. When students who say they are comfortable sharing their opinions on controversial or sensitive topics in class are asked why, more than 40 percent say they are comfortable because they believe their views align with most other students and professors. Moreover, over the four years of our survey, large percentages of students have consistently said they favor illiberal actions regarding speech. This includes one-third saying that speakers with unpopular views should have university invitations withdrawn, and more than one-third saying readings that make students uncomfortable should be dropped from class requirements. More than one-quarter say class discussion topics that make students uncomfortable should stop being discussed.

The most telling evidence of a restrictive campus environment comes from student answers on whether their professors and fellow students should be punished for saying things they disagree with. When students were asked whether professors who say something that students find offensive should be reported to the university, more than 68 percent of students said ‘Yes’ in every year of the survey. When asked whether fellow students should be reported for saying something that is deemed offensive, more than 56 percent said ‘Yes’ every year.

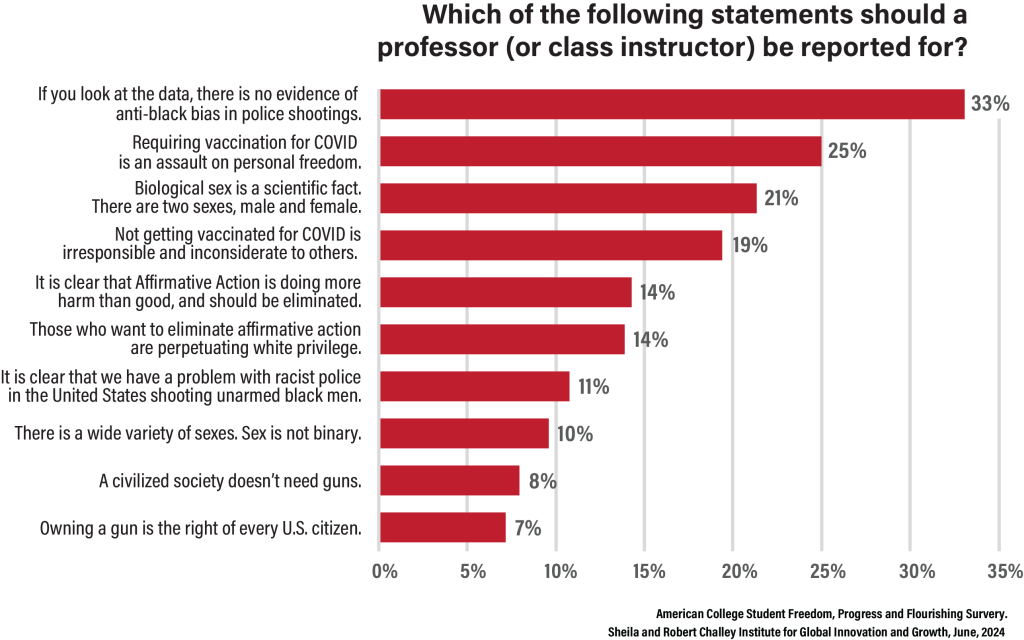

To verify that these answers suggest an intolerance of different points of view and not a concern over racial slurs, sexual harassment and personal attacks, we asked students to identify whether professors should be reported to the university for making various statements related to affirmative action, policing, guns, sex/gender and vaccines (opposite). In the two years that we asked this question (2023 and 2024) more than 62 percent of students said that professors should be reported for making one or more of these statements of fact or opinion. For students who report being liberal or liberal-leaning, three-quarters say professors should be reported for making one or more of these statements.

Further analysis supports the idea that the campus climate is not as open to diverse viewpoints as surface-level questions suggest. After controlling for political ideology, socioeconomic status and gender, we found that students who believe their campus is open to diverse and unpopular views are also more likely to support actions that prevent others from speaking—such as disinviting speakers, dropping controversial readings, and reporting students and professors who express offensive views. This points to an environment where certain viewpoints are accepted, but others are not.

These results are concerning given the central role that U.S. universities play in innovation and in training future leaders who will spur innovation in private industry. Moreover, calls for censorship of social media that started during the Covid-19 pandemic and efforts to suppress dissenting scientific views should raise concerns about the future of American innovation.i Not only does this type of censoring or suppression prevent new ideas from emerging, it also makes people less trusting of the academic, governmental and media institutions that help to convey current knowledge.

Tribalism

As highlighted by a recent piece by Ben Klutsey, this lack of trust in “the reality-based community” makes people resort to epistemic tribalism.ii Instead of looking at the evidence from a variety of perspectives and with full information, they resort to incomplete information and speculation from within their own communities. This separation of idea exchange into individual communities further diminishes the broad exchange of ideas that leads to innovation.

Unaware of Progress

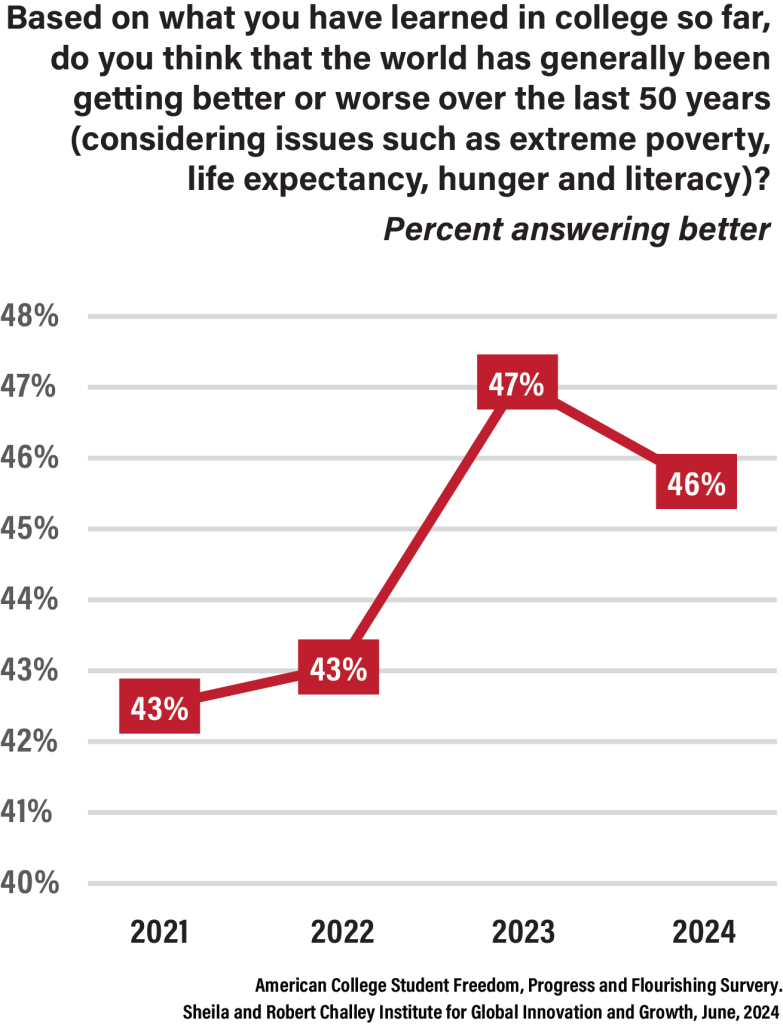

Our survey results also show that many students lack awareness of the tremendous progress made globally and in the U.S. over time, in areas such as extreme poverty, life expectancy and literacy.iii In any of the four years of our survey, when students were asked whether the world has been getting better or worse over the last 50 years in terms of extreme poverty, life expectancy, hunger and literacy, less than half of students have said it has improved (Figure 2). Similarly, just over 40 percent of students think the U.S. has improved over the last 50 years in terms of life expectancy, per capita income and education level.

Not surprisingly, this fuels a lack of optimism among students about the future of the world (less than 30 percent optimistic in any year of the survey), the future of the U.S. (about a quarter of students in any year) and their own futures (just over half in any year). This optimism often motivates individuals to take actions (including those leading to innovations) that further human progress.iv

Misunderstanding Capitalism

Survey results also show a widespread misunderstanding of capitalism among students. While more than half of students define capitalism as free market capitalism in our most recent survey, about 40 percent of students confuse capitalism with cronyism. This leads to skepticism about capitalism, with only 27 percent having a positive view in our most recent survey. This type of confusion is likely to lead to a destructive spiral in which people attribute problems resulting from cronyism to capitalism and call for policies that require more government intervention in the economy.v This leads to more opportunities and incentives for firms to engage in cronyism, resulting in additional distrust of capitalism.

To illustrate this kind of unvirtuous destructive spiral, consider the supply chain disruptions during and after the Covid-19 pandemic. Some blamed capitalism for the problemsvi when much of the problem was rooted in cronyism. U.S. companies experienced delays in receiving imported products to meet consumer demand and experienced rising shipping costs, while exporters were unable to get containers to ship their products elsewhere.

While port congestion and delays in 2021 and 2022 were certainly much the result of a spike in imports due to pandemic recovery, cronyism also played a major role in the problems experienced at U.S. ports. Scott Lincicome, JD, a policy scholar at the Cato Institute, highlights factors catering to special interests that were major contributors to the problems.vii First, provisions in labor union contracts made U.S. ports less efficient, including limiting hours of work, inflating labor costs and fighting automation. In fact, in 2021, when these delays were at a peak, the two largest container ports in the U.S.—Los Angeles and Long Beach—ranked last and second to last in the World Bank’s Container Port Performance Index.viii

Second, the Jones Act and the Foreign Dredge Act, two U.S. maritime laws, which are also heavily supported by union lobbying, reduced the ability of ships to travel between U.S. ports and made it expensive to dredge ports to accommodate larger ships. The Jones Act prevents non-U.S. owned, built and crewed ships from transporting products between U.S. waterway ports, while the Foreign Dredge Act applies the same rules to dredging material. These restrictions led to increased congestion on in-land modes of transportation.

Lastly, trade-remedy import tariffs on truck chassis contributed to large price increases on truck chassis and limited the ability of U.S. freight carriers to get them. These trade-remedy import tariffs, which were the result of an investigation done at the request of U.S. chassis manufacturers, also contributed to limited transportation capacity.

As a result of the disruptions, many called for reshoring supply chains by imposing trade tariffs and other incentives. Not only does this harm consumers and taxpayers, but it also incentivizes firms to lobby to influence the products that are charged tariffs and receive subsidies. This misplaced energy on lobbying directly harms innovation by consuming resources that would otherwise be used for innovation. In addition, fostering further mistrust of capitalism leads to more policies that dull incentives for innovation.

Role of Universities

These survey results suggest that if universities are to fulfill their roles in enabling innovation and training future innovators, they need to change. Students need to be exposed to alternative viewpoints to engage in critical thinking. Moreover, they need an appreciation for the positive role of viewpoint diversity in innovation and an ability to interact with others who see things differently. As well, they need to understand the world’s progress and the role that free market capitalism has played in fueling that progress. Not only will this enable them to appreciate and advocate for policies that will allow progress to continue, but this will also help them envision future progress and the role they can play in advancing it.

The types of student programs that can help universities improve are being implemented at the Challey Institute. We offer reading groups that challenge students to explore important questions from various perspectives while engaging in constructive dialog with students who may or may not agree with them. Similarly, our pluralist lab allows students with different political views to discuss controversial topics. We offer a workshop where students learn about human progress and its causes, and where students gain insights from internationally renowned scholars on solutions and policies that contribute to opportunity, innovation, and individual and societal flourishing. We offer a course that teaches students about different types of economic systems, including capitalism and socialism, and their implications. Our Menard Family Distinguished Speaker Series provides a venue for students, faculty and the public to learn from world thought leaders on ways to improve the human condition and create economic opportunity. Although other university centers and institutes are doing similar things, this effort needs to be extended more broadly across higher education and to more students within universities. Universities play an important role in our nation’s future prosperity and culture of innovation. Higher education needs to take the lead in fostering an appreciation for the value of viewpoint diversity, the progress we have made and the important role of freedom in this progress. By doing so, universities can help ensure that America will remain a leader in innovation. ◉

REFERENCES

i Editorial Board. “How Fauci and Collins Shut Down Covid Debate,” The Wall Street Journal, December 21, 2021. ii Klutsey, Ben. “To Conquer Our Biases and Improve Our Knowledge, We Need Epistemic Liberalism,” Discourse, September 23, 2021. iii Data on human progress in these and other areas can be found here: https:// humanprogress.org/datasets/ iv Bitzan, John and Clay Routledge. “Is there a relationship between knowledge of human progress and student optimism? Challey Institute Research Brief, November 2021. https://www.ndsu.edu/fileadmin/challeyinstitute/Research_ Briefs/Research_Brief_2021.02.pdf v Klein, Peter G., Michael R. Holmes, Jr., Nicolai Foss, Siri Terjesen, and Justin Pepe. “Capitalism, Cronyism, and Management Scholarship: A Call for Clarity,” Academy of Management Perspectives, 36(1), 2022. vi Selwyn, Benjamin. “Limits to Supply Chain Resilience: A Monopoly Capital Critique,” Monthly Review: An Independent Socialist Magazine, March 1, 2023. vii Lincicome, Scott. “America’s Ports Problem is Decades in the Making,” Cato Institute, September 22, 2021. https://www.cato.org/commentary/americas-ports-problem-decades-making viii The World Bank, “The Container Port Performance Index 2021: A Comparable Assessment of Container Port Performance,” World Bank, Washington, D.C., 2022.

John D. Bitzan, PhD

John D. Bitzan, PhD, is the Menard Family Director of the Sheila and Robert Challey Institute for Global Innovation and Growth and a Professor of Management at NDSU. He studies

transportation economics, the impacts of regulation, and market structure and performance. His research has spanned public policy issues related to railroads, airlines, motor carriers, waterways and public transit, including examining economic issues such as transportation costs, energy consumption, pricing, profitability and regulatory change. Prof. Bitzan has co-edited

three books on transportation economics and published research in top academic journals including the Southern Economic Journal, Journal of Law and Economics, Journal of Transport

Economics and Policy and Review of Industrial Organization. His work has also been published in Entrepreneur magazine, The Wall Street Journal, The Hill, Washington Examiner, Newsweek and Reason magazine. He received his MA in Applied Economics from Marquette University and his PhD in Economics from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.