AI as Problem and Solution

Artificial intelligence (AI) is advancing at a startling pace, and society is grappling with AI’s potential to be both beneficial and harmful. “Deepfakes” are one of the harms enabled by AI that has begun to show AI’s potential to spread misinformation, sow distrust, and enable fraud and other criminal acts. Law and technology experts have also begun to sound the alarm on the threats, which deepfakes may pose to fair adjudications in courts of law, as AI has the potential to permit inauthentic evidence to be admitted at trial, while simultaneously allowing authentic evidence to be rejected based upon improper claims of inauthenticity.

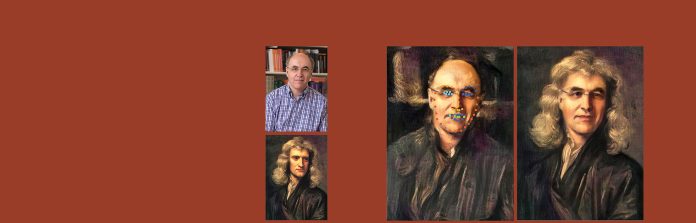

In a deepfake, AI is used to create a new—and fake—image, video or audio, based upon a “sampling” of actual images, video or audio of a real person. For example, deepfake technology could scan the video of an actual political speech, delivered by a real politician, and then create a fake video purporting to contain a speech delivered by that same politician. The term “deepfake” is derived from the process used to create fake images, videos and audio, which uses “deep learning” algorithms that process real-life data (such as voice patterns and images of a real-life speaker) to then produce fake output (such as phony audio and video of that same speaker).

Deepfakes may be used for a variety of malicious purposes, with the common goal of tricking the public into believing that a person said or did something that the person did not actually say or do. Deepfakes have targeted politicians, such as one deepfake video purporting to show President Barack Obama launching into an obscenity laced tirade against President Donald Trump, and another deepfake distributed by a Belgian political party purporting to show a speech delivered by President Trump urging Belgium to withdraw from an international agreement.i

Deepfakes have also been distributed to vilify public figures and leaders of industry, such as a recent deepfake purporting to show Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg bragging about having “total control of billions of people’s stolen data.”ii Deepfakes have also been used to commit crimes. For example, one criminal scheme involved scammers, using deepfake technology to impersonate the voice of a relative, placing desperate calls to unwitting victims, pleading for the victims to quickly transfer funds due to a phony emergency.iii

Liar’s Dividend

Legal experts predict that as deepfakes become more prevalent and difficult to detect, they will increasingly be the subject of evidentiary disputes in litigation. Deepfake technology has become easily accessible in recent years, and experts predict that parties will increasingly attempt to introduce evidence into court that is actually a deepfake.

Additionally, experts predict that legitimate audio, videos and images will increasingly be challenged in court as being deepfake in a phenomenon known as the “liar’s dividend.” According to the liar’s dividend, as society “becomes more aware of how easy it is to fake audio and video, bad actors can weaponize” that skepticism. Because a “skeptical public will be primed to doubt the authenticity of real audio and video evidence,” actors can raise bad faith challenges by alleging that authentic evidence is actually deepfake.iv Consequently, if “accusations that evidence is deepfaked become more common, juries may come to expect even more proof that evidence is real,” which could then require parties to expend additional resources to defend against unfounded claims that authentic evidence is fake.v

A recent high-profile example of a deepfake claim being raised in court to cast doubt upon an authentic video occurred in a wrongful death case pending against automaker Tesla, where the court rejected Tesla’s assertion that a widely publicized video of CEO Elon Musk being interviewed at an industry conference in 2016 is a deepfake. The court found Tesla’s assertion here to be “deeply troubling,” and the court responded to Tesla’s assertion by ordering a limited deposition of Musk on the issue of whether or not he made certain statements at the 2016 conference.vi

Detecting Deepfakes

Attorneys should be prepared to address deepfakes in their practices as deepfakes become more commonplace. The following are signs that a video, audio or image could be a deepfake:

Unreliable, questionable sources: Deepfakes are usually shared, at least initially, by unreliable, questionable, non-mainstream sources. If, for example, the originator of a videoed speech by a high-profile person is an unknown online entity, there is a strong likelihood that the recording is a deepfake.

Blurriness: In deepfakes, the target will often appear blurrier than the background.

In particular, the hair and facial features of deepfake targets often appear blurry compared with other aspects of the video or image.

Mismatched audio: Deepfake visuals are often produced separately from deepfake audio, and then “stitched” together to create a final video. Consequently, visuals and audio can be misaligned, resulting in a mismatch between what is seen and what is heard. If, for example, there is a delay between what is heard and the movement of the speaker’s mouth, such that it appears as though the speaker is lip-synching, this is a strong indication that the video has been deepfaked.

Mismatched lighting: Deepfakes will often retain the original lighting from the source video or image and transpose the original lighting into the new video or image, thus causing a mismatch of lighting within the final deepfake. If a video or image contains unusual, inexplicable shadowing, this is a telltale sign that it has been altered and might be a deepfake.

AI to Detect Deepfakes

As deepfake technology progresses, it will become difficult, and eventually impossible, for the human eye to detect deepfakes. Consequently, it will become necessary for attorneys to rely upon AI to detect deepfakes. Stated differently, we will need to rely upon AI to detect the works of other AIs, thus leading to an arms race between deepfake creators and deepfake detectors. In any event, attorneys should plan for a future in which they must safeguard against being fooled by deepfakes, be able to identify and counter deepfakes offered by their opponents in evidence, and be able to defend against bogus accusations that their own proffered evidence is deepfake. ◙

This article was originally published in the June 2023 issue of Wyoming Lawyer.

References

I Ian Sample, “What are Deepfakes – and How Can You Spot Them?”, The Guardian, January 13, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2020/ jan/13/what-are-deepfakes-and-how-can-you-spot-them; Hans Von Der Burchard, “Belgian Socialist Party Circulates ‘Deep Fake’ Donald Trump Video,” Politico, May 21, 2018, https://www.politico.eu/article/spa-donald-trump-belgium-paris-climate-agreement-belgian-socialist-party-circulates-deep-fake-trump-video/

ii Von Der Burchard, supra note 1.

iii Pranshu Verma, “They Thought Loved Ones Were Calling for Help. It was an AI Scam,” Washington, March 5, 2023, https://www.washingtonpost.com/ technology/2023/03/05/ai-voice-scam/

iv Shannon Bond, “People Are Trying to Claim Real Videos are Deepfakes. The Courts are Not Amused.” NPR, May 8, 2023, https://www.npr.org/2023/05/08/1174132413/people-are-trying-to-claim-real-videos-are-deepfakes-the-courts-are-not-amused

v See id.

vi “Elon Musk’s Statements Could Be ‘Deepfakes,’ Tesla Defence Lawyers Tell Court,” The Guardian, April 26, 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2023/apr/27/elon-musks-statements-could-be-deepfakes-tesla-defence-lawyers-tell-court